V&A Online Journal

Issue No. 7 Summer 2015

ISSN 2043-667X

Out of the Shadows: The Façade and Decorative Sculpture of the Victoria and Albert Museum, Part 1

Melissa Hamnett

Curator, Sculpture, V&A

Abstract

Figure 1. Bird’s eye view of the Aston Webb extension, highlighting the full 12,120m2 footprint of the site. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In 1909, the architect Sir Aston Webb completed a three-storey façade extension to the Victoria and Albert Museum (fig. 1). Built at a time of rising wealth and public patronage, coupled with unprecedented innovation across industries, the Webb wing – spanning a 12,120m2 site – reflects the emergence of new civic centres with buildings that had greater input from pioneering contemporary sculptors. At a time when national pride and modernity were intersecting in prominent urban spaces through sculpture and architecture, this first article (of three) summarises sculpture’s initial subordination to architecture, their growing symbiosis and the increasingly collaborative role that artists of the New Sculpture movement played in these emerging public buildings.

Introduction

The Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) was central in the development of modern British sculpture.(1) Founded in 1852 with profits from the 1851 Great Exhibition, the Museum emerged from wider debates in the 1830s and 1840s on British art and manufacture, coupled with a growing anxiety about the perceived superiority of French design.(2) While the institution’s early formation was an attempt to foster British self-confidence on the part of design reformers, manufacturers and politicians, its expanding site also highlights the changing rapport between architects and sculptors that was to pave the way for a new sculptural aesthetic. Purposely built for the education and enjoyment of the public, and seen as a model for comparable institutions across Europe, the V&A’s core aims were to make the fine and applied arts available to all, to educate working people and to inspire and teach British artists, designers and manufacturers.(3)

The building itself reflects these aims. Using new methods and materials, leading sculptors of the New Sculpture movement were employed to carve key British artistic figures in the niches of the two façades.(4) Akin to a shop window celebrating British output, the sculptors of these carved figures also employed students from some of the leading London art schools as apprentices, providing opportunities for creative and professional development. Underlining Britain’s achievements in the fine and applied arts, the design and execution of the V&A’s Aston Webb façade was a physical manifestation of the Museum’s founding principles (an argument that will be examined in more detail in the second article).

Known as the Museum of Manufactures when it opened at Marlborough House in 1852, the institution was renamed the South Kensington Museum in 1857, when it moved to its current site on what was then the edge of west London. The name of this early building (belittlingly dubbed the Brompton Boilers by The Illustrated London News in 1857)(5) remained so for more than four more decades until, in 1899, it was renamed the Victoria and Albert Museum.(6) This event was marked by Queen Victoria (1819-1901), who laid the foundation stone for a new and imposing grand entrance designed by the architect, Sir Aston Webb (1849-1930) (figs 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Official programme for the laying of the Foundation Stone of the Victoria & Albert Museum, unknown maker, London, 1899, letterpress, blue ink on pink paper. Museum no. E.1458-1984. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Figure 3. Detail of the V&A’s Grand Entrance doorway on Cromwell Road. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Aston Webb’s design had won the 1891 competition administered by the Office of Works, who had invited eight architects to compete in a bid to unify the haphazard site of the South Kensington Museum at the end of the 19th century.(7) The act of renaming the museum marked a triumphant and imperialist phase in the history of the V&A, expressed through Webb’s entrance and façade, which was described by him in a 1909 guide as ‘a great portal finished by an open lantern of the outline of an Imperial crown to mark the character of this great national building’.(8) A key feature of this vast redbrick and Portland stone façade is the elaborate sculptural scheme bridging Cromwell and Exhibition Road (fig. 4). A British Valhalla, it depicts 32 artistic personalities carved by 21 different sculptors. Those depicted include British painters, sculptors, architects and craftsmen who stand within niches between the first floor windows across the entire length of the façade. This is in addition to the arched entrance and central tower adorned with figures of Prince Albert and Queen Victoria. Conceived by Webb to be a vision for the modern museum, his sculpted façade signified the reinvention of Britain in a highly competitive Europe by embracing the spheres of fine and applied art, and articulating a new national consciousness.(9) Accordingly, the architecture integrated traditional precedents, such as the standing niched personages, whose selection and execution was meant to highlight the joining of art and industry. The sculpture was not only a physical manifestation of skill and virtuosity, for the sculptors who carved it were themselves also promoting a new collaboration between multiple professions in a bid to improve the infrastructure of education and patronage, which were to be vital for sculpture’s success.(10)

Figure 4. Black and white photo showing the corner of Exhibition Road and Cromwell Road and the sculpted figures in the second floor niches, Bolas & Co., South Kensington, London, 1909, albumen print. Museum no. E.1128-1989. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Despite sculpture’s increasing public presence in Britain from the 1850s onwards, the V&A’s elaborate façade attracts little attention today.(11) Indeed, if passers-by do not take note of the carved figurative subjects, still less do they recognise their sculptural authors. Webb’s extension united what had become a rather piecemeal and confusing complex of buildings by the 1880s, and highlights the associated shift in the relationship between sculpture and architecture. Not only did the building form part of South Kensington’s budding new cultural and technology epicenter, known as Albertopolis,(12) but the sculptural scheme also articulated how craft and industry were increasingly considered interconnected spheres, with Britain and its empire triumphant symbols of economic and cultural change.(13) Conveying narrative and meaning beyond its construction, the façade and its execution can accordingly be seen as a material expression of this wider emerging modernity.

This first article (of three) will provide the wider background to the changing alliance between sculpture and architecture, with particular reference to Webb’s V&A façade, by considering the broader changes taking place in sculpture’s production, location and consumption from the 1850s onwards. This will be examined in part through studying the population shift from rural to urban areas in the early 19th century, and the impact after 1850 of Britain’s inhabitants increasingly becoming city dwellers. It will consider how these changes affected the relationship between sculpture and architecture from the 1870s onwards, resulting in a new set of parameters for sculptural practice in Britain led by practitioners of the New Sculpture, by whom at least 17 of the V&A’s niched figures and all the main entrance work was carried out.(14) The second article will look in detail at how the prevailing desire to find a modern idiom for three-dimensional sculpture was played out in the design and execution of the Webb building, and how it supported the broader context of the institution’s founding ethos. I will particularly focus on how the sculptors who collaborated on the façade actively sought out new connections between sculptural representation and its immediate historical context. Essential to sculpture’s changing ideology and Webb’s V&A façade was the New Sculpture, whose practitioners changed how sculpture was being seen and encountered in the late 19th century. They dominated the rise of what is known as Edwardian Baroque architecture,(15) a term that refers to the architectural style of public buildings built in Britain during the Edwardian era (1901–10), many of which unify art and industry with pedagogy. Given this link, the role of the New Sculpture in the V&A façade will also be considered within the wider prevailing ideologies of art, design and education. My third and final article will examine how this paradigm shift in sculpture affected its role in both public and private contexts in the early 20th century. By examining changes in how sculpture was being made and understood, it will explore the wider output of the New Sculpture, and how the changing identity of the sculptors who worked on the façade accordingly affected subsequent artists and sculptural practice.

Urban growth and the alliance of sculpture and architecture

The emerging market for the dissemination of, and education in, good design depended on the development of a wealthier middle class who consumed these goods at home, in public and through museum or gallery environments.(16) This transition had, in part, come about through a major shift in the balance between Britain’s rural and urban population. It not only saw fundamental changes occur within major cities and towns where sculpture increasingly played a part, but also in the relationship of urban spaces to British society as a whole.(17) The growth of the administrative county of London in particular was rapid in both geographical area and population numbers, rising from 3,000,000 in 1860 to 4,500,000 by 1900. Greater London grew faster still, and between 1871 and 1891 it expanded more quickly than the national population as a whole.(18) As cities in Britain were redesigned due to the shifting the urban demographic, and the growing middle classes concurrently became wealthier, the market for art expanded exponentially. With regards to sculpture, this had an impact on production, location and display. The state commissioned sculpture for new buildings and public squares, provincial towns bought it through subscription and philanthropy, and technical innovations in casting and reproductions saw a new group of dealers selling it to museums and collectors.(19)

In southwest London specifically, the embryonic South Kensington Museum, with its medley of temporary buildings and growing collections, was in need of rationalisation; old brick houses occupied the southeast corner of the estate, wooden sheds that had moved from Marlborough House were covered in corrugated iron for the Schools of Design, and brick galleries in a north Italian Renaissance style had been chosen for the lecture theatre and paintings galleries. Refreshment rooms, storehouses, and various other structures, all of a provisional and economical kind, accordingly gave the grounds of the museum a divided and miscellaneous character.(20) Aston Webb’s extension marked the V&A’s development from a ‘Museum of Manufactures’ to an institution that actively promoted the alliance between art, craft and industry. This was not only reflected in the Museum’s increasingly diverse holdings but also through its cohesive and sculpted façade. While the carved personages on the Webb exterior show homage to both the fine and applied arts, the sculptors who carved them were likewise not just confined to statuary but gradually also embellished products ranging from domestic goods such as decorative ornaments, to street furniture such as lampposts and fountains.(21)

Figure 5. City Square Leeds, photograph, unknown photographer, Leeds, 1905. © Leeds Library & Information Services

While this was happening in Britain, parallels can be similarly drawn with other European cities, such as Paris, Barcelona and Amsterdam, albeit slightly later. These developments were sometimes accentuated by the late 19th and early 20th century World Fairs, where the growing prominence of sculpture was in part led by these international exhibitions and where new technical innovations in sculpture were often exhibited.(22) However, sculpture’s ubiquity was also a consequence of the mounting need for town planners to bring order to the unprecedented urban growth. In Britain, city streets were gradually populated with civic buildings and communal squares, which were felt to need embellishment to give them a greater sense of identity (fig. 5).(23) While the Church continued to commission sculpture of this period (as was historically the case), the Government notably became its new chief patron with civic centres, such as London, Liverpool, and Glasgow, dominating production.(24) As a result, professional sculptors were increasingly employed to provide focused definition in the form of memorial statues, carved decoration and fountain displays, in a bid to enhance the new spaces made possible by municipal planning.(25)

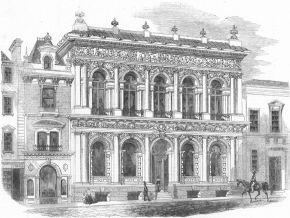

Initially, civic sculpture was produced under the auspices of commissioning committees with professional organisations, such as the Royal Academy,(26) and educational establishments, such as the Glasgow School of Art,(27) involved in adjudicating competitions. It was through such tradition and training that contemporary sculptors met the expectations and values of the institutions endorsing them as professional. This is particularly evident from the 1850s onwards, when sculpture was added to the exteriors of law courts, theatres, libraries and banks, as new seats of government, culture, learning and commerce called for new buildings and headquarters.(28) The chain of command often involved large teams of anonymous sculptors working on surface decoration, rather than independent sculpted works being integrated into the whole. This can be seen in the decorative scheme for the former Bank of West England and Wales (fig. 6), built between 1854 and 1858, where over 20 sculptors were employed at the close of the building project to add decorative friezes, designed solely by the architects.(29) Showing similar traits (prior to its bombing in 1940), was the Carlton Club in London’s Pall Mall. Built between 1854 and 1856 by Sydney Smirke (1798-1877), the decorative frieze at the top of the building is seemingly incongruous with the rest of the Venetian Renaissance-style façade.(30)

Figure 6. An unsigned print of the decorative scheme for the former West of England and South Wales District Bank, Bristol. Illustrated London News, August 9, 1856, issue 815, 136. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Early examples, such as this, highlight how sculpture was still divorced from the architectural whole, considered all too late in the building’s scheme, and habitually manifested as a last minute appendage. With no serious consideration, sculptural decoration acted simply as a filter to the architecture, its authors, position and function deemed secondary. This was exacerbated by practitioners of Gothic Revival architecture, such as George Scott (1811-78), who designed the Midland Grand Hotel at St Pancras (1868-76) (fig. 7) or Charles Barry (1795-1860) and Augustus Pugin (1812-52), who were responsible for rebuilding the Palace of Westminster (1840-60). In both instances, the exterior sculpted decoration was treated more as ‘common architectural ornament’, rather than as works of art in their own right and, while not of poor quality, was applied with no real sense of harmony.(31) Moreover, it was carried out by large teams of unknown architectural carvers who executed the architects’ vision from arms’ length, rather than by sculptors who collaborated with the architect to self-consciously define their work and the function of the building. In combination, these factors undermined artistic autonomy and artisanal practice on an individual level.(32)

Figure 7. The Midland Grand Hotel at St Pancras, London © CC.BY-SA.3.0

As London’s civic map continued to grow throughout the 1860s and 1870s, sculpture’s frequent divorce from, and secondary position to, architecture became increasingly marked. This was highlighted in an 1861 essay entitled British Sculpture: Its Condition and Prospects, by William Rossetti (1829-1919), the younger brother of the Pre-Raphaelite painter. Rossetti argued that ‘if sculptors could only learn how to invest their work with expression and character and bring it out of the exhibition gallery into the bustling city streets, public interest would be aroused again’.(33) While his comments highlight the gulf that existed between architectural carving, modelling and ‘high art’, they also (perhaps unfairly) implicitly blame the sculptor, who was often in fact carrying out the wider vision and design scheme of the architect. Serious consideration of sculpture and its civic role resurfaced in the British Architect in April 1874, a journal that had first appeared in January of that year and remained a determined champion of sculpture’s cause for the rest of the century.(34) The view that architectural decoration was somehow unworthy of consideration as art was seen to be the result of an enforced separation between ‘the sculptor proper’ and ‘commercial or architectural carvers’, the latter largely associated with specific large workshops such as Farmer and Brindley.(35) This separation of the conceptual side of sculpture (the work of the imagination) from the manual side of sculpture (the actual physical making) meant that contemporary commentators and architects thought it almost impossible for ‘the sculptor proper’ to embellish cohesively public buildings.(36) Critics who tended only to accept memorials or gallery sculpture as genuine works of art further compounded this view. Notable comparisons can be drawn here with European buildings such as Paris’s Hotel de Ville, built between 1873 and 1892, where 230 sculptors – amongst them Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) – worked on individual figures that were subordinated to the overall façade scheme, while the practitioners remained largely unknown and unacknowledged.(37) Likewise, the sculpture on Stockholm’s 1908 Royal Dramatic Theatre is frequently overlooked, despite the involvement of renowned Swedish sculptors such as Herman Neujd (1872-1931) and Carl Milles (1875-1955), the latter a former assistant to Rodin.(38)

Figure 8. Athlete Wrestling a Python, Frederick Leighton, 1877, as displayed in the V&A’s Dorothy and Michael Hinzte Sculpture galleries in 2007. Loan from Tate, museum no. N01754. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The idea that figurative sculpture as applied decoration could be considered as art, enhancing the new urban environment, and yet divorced from any commemorative role, was radical in 1870s Britain. Frederic, Lord Leighton (1830-96), better known as a painter, was amongst the first to try to formulate a new direction for sculpture and, while not conceived for an architectural setting, his acclaimed Athlete Wrestling a Python of 1877 (fig. 8) sought to elevate sculpture from its subordination to painting through the dynamic representation of the human body. Leighton’s piece was seen as a catalyst for the emerging New Sculpture movement, capturing the genre’s expressive and naturalistic possibilities with its vigorous depiction of a muscular figure braced in struggle with a huge coiling serpent.(39) Retrospectively coining the term, ‘The New Sculpture’, in his seminal 1894 Art Journal essays, the art critic Edmund Gosse saw Leighton’s Athlete as epitomising a sculptural reawakening through its truth to nature and re-evaluation of sculptural composition.(40) But, while Leighton’s work certainly threw into question the conventional format and context of the freestanding ideal statue (epitomised by practitioners of Neoclassicism), it was seven years before interest in blending sculpture and architecture into a more sympathetic whole began to intensify.(41)

The Arts and Crafts movement undoubtedly played a part in enabling architects to associate more with artists and sculptors, as the foundation of guilds and societies encouraged a reaffirmation of art’s relevance in society through collaborations with industry and commerce.(42) This was reinforced by the need to forge a new national identity to compete in international markets, endorsed by government-sponsored patronage that ruptured old systems of production. For architecture, this resulted in the displacement of the ‘aggressive and assertive Gothic Revival style, in favour of a more rational and technological spirit, epitomised by the Edwardian Baroque’.(43) It essentially combined ebullient classical features, such as heavy rustication and weighty ground floor arches, with British imperial elements like turrets, heraldry and domes, facetiously termed ‘Wrenaissance’ after Sir Christopher Wren.(44) This was typically finished with expressive allegorical and figurative sculpture, which was comprehensively integrated, the parts all belonging to the whole yet clearly individually considered.(45)

A key point in the advent of Edwardian Baroque was in 1884 when John Belcher (1841-1913), one of the leading architects of the period, founded the Art Workers’ Guild with Hamo Thornycroft (1850-1925), a young practitioner in the New Sculpture movement.(46) The Art Workers’ Guild pledged to unite the aesthetic arts in Britain through constructive dialogue between artists and artisans, and vowed to establish a more modern dialogue between architects and sculptors.(47) This accorded with the growing need for large-scale city buildings from architects whose modernity was increasingly judged by their interest in collaboration.(48) As Europe’s thriving industrial economies were churning out new machines and products, hundreds of thousands of people were being drawn into its cities with the promise of prosperity and excitement. In an age of extraordinary progress where architects, sculptors and designers were ushering in a new period of urban change, experimentation went hand in hand with collaboration as the idea of art in a public context, and cross-disciplinary approaches to building, were gradually perceived as enhancing the urban environment.(49) The diversity and interconnectedness of sculptural practice provided architects with new ideas and processes that departed from their normal approach, while sculptors were likewise reassessing their approach to materials so that their contributions could more effectively take a place in the façade as a whole.(50) Sculpture, it was felt, should no longer be simply added on to a building like an ill-thought addendum, but jointly considered by the architect and the sculptor from the beginning. In his Essentials in Architecture, Belcher advocated the considered cohesion of sculpture from the start as a fundamental part of any edifice, ‘Whatever be the purpose of a building, there should be no feature, ornament or line, which has not a definite end or meaning or which is not an integral part of the architectural scheme from the start.’(51) He went on to add that ‘the artistic element must neither override the practical or the scientific, nor yet be superimposed upon it, but must work with it. The two aspects […] are so blended that though they may be distinguished in thought, they cannot be separated in operation’.(52)

Figure 9. The external façade of London’s Institute of Chartered Accountants. © Melissa Hamnett, 2013

By the late 1880s, the promotion of integrating art and industry was receiving considerable attention and, in 1888, the first national congress of the Association for the Advancement of Art and its Application to Industry was held in Liverpool.(53) The congress was presided over by Lord Leighton – a keen supporter of technical and stylistic innovation in sculpture – and chaired by Alfred Gilbert (1854-1934), a New Sculptor and close associate of Thornycroft.(54) The focus of the day was how to reconcile the methodology and design ideology of the Arts and Crafts with a new architectural style that could communicate those ideas in a fresh and culturally invigorating way. Belcher’s contribution to the congress was a paper directed against the stylistic conventions of previous decades, which called for all architects to treat the work of sculpture ‘as a jewel whose beauty is to be enhanced by an appropriate setting’.(55) He cautioned against adding applied ornament at the end of a building project for the sake of simply varying texture, profile or silhouette. Instead he advocated the use of figurative sculpture and fresco work to provide unity.

Belcher’s paper raised pertinent points related to his own work, since he was just embarking on the design for London’s Institute of Chartered Accountants in 1888 (fig. 9), a twin project with his fellow Guild founder, Thornycroft. The building was pioneering in terms of its formal innovation and forward-looking design and, thanks to Belcher’s and Thornycroft’s belief in the unity of all arts, it physically manifested the prevailing values of design reformers like Sir Henry Cole (1802-92), to modernise industry by contesting its false separation from art.(56) Belcher and Thornycroft captured these values through a series of carved relief panels representing ‘arts’, ‘science’, ‘craft’, ‘commerce’ and ‘education’, coupled with figurative sculpture on the rusticated Portland stone masonry. The cohesion of the sculpture on the building’s façade not only testified to a new partnership between architect and sculptor, it also reflected belief that the union of art, education and commerce had the power to boost the empire and transform society. This view was heavily promoted by Cole, a central figure in British art and design education whilst Director of the South Kensington Museum from 1857-73. Cole disseminated these beliefs via the National Art Training Schools, which he was instrumental in developing, and from which other art schools such as Brighton, Glasgow and Birmingham took their lead.(57)

Figure 10. The external façade of Lloyd’s Shipping Register building. © Melissa Hamnett, 2013

On the building’s completion in 1893, it was reported in The Times that, ‘one would give whole streets full of frippery for a building designed with the courage and sincerity of the Institute of Chartered Accountants, whose modernity has the power to lift one’s experience of the street, one’s experience of it and even the nation as a whole’.(58) Echoing this scheme, and arriving not long after it in 1900, was another London building known as the Lloyd’s Shipping Register (fig. 10). Here, George Frampton (1860-1928), a New Sculptor and Master of the Art Worker’s Guild, collaborated with the architect Thomas Edward Collcutt (1840-1924) on the naturalistic allegorical frieze reliefs depicting Virtue and Industry.(59) It is significant that in 1891, when the Treasury and Office of Works invited eight architects to submit design entries for a new V&A façade, both Belcher and Collcutt were amongst those asked to participate alongside Aston Webb, who ultimately won the commission.(60)

Figure 11. Detail of Amsterdam’s Beurs van Berlage (Stock Exchange building). © Melissa Hamnett, 2013

As architectural and sculptural collaborations became increasingly widespread towards the end of the 19th century, European cities similarly reflected this trend, as their cityscapes expanded and civic buildings were embellished. The Netherlands in particular embraced these new partnerships, exemplified by Amsterdam’s Beurs van Berlage (Stock Exchange building). Built between 1896 and 1903 by the architect, Hendrick Petrus Berlage, and the sculptor Lambertus Zijl, the collaboration can be seen through the frieze panels and poetic verses on the façade (fig. 11), the latter echoing the architect’s wish for the building and its reliefs to be seen as one.(61) In France, the façade likewise became an increasingly important place where the sculptor could be actively involved in the edifice, illustrated by the Théâtre des Champs Elysées, where Émile-Antoine Bourdelle worked alongside the architects van de Velde and Perret.(62) Traditionally most British sculptors were trained to work under the supervision of architects, but following Thornycroft’s lead in Britain on the Institute of Chartered Accountants, a precedent had been set for redressing the balance of future collaborations and bringing sculpture into alliance with architecture.(63)

The new explorations in the

1880s supported and enabled a transformation in the practice, theory and

reception of sculpture, and saw certain architects increasingly

predisposed towards giving sculptors a more defining role in the early

20th century. Aston Webb, like Belcher, was one such architect that I

will explore in more detail in the second article, which focuses in

depth on the V&A’s façade sculpture and sculptors. Aside from

the sense of a new national consciousness merging with nascent concepts

of modernism, it will become clear on investigating the façade that

practitioners of the New Sculpture moved away from the static appearance

of 19th-century neoclassical figures towards an ‘interplay between the

physical presence of the statue and the figural representation it

conveys’.(64) Such explorations were only possible due to a period of

shifting urban and economic growth, the changing relationship between

architect and sculptor, and the complex interconnections between

government-sponsored building, education and culture. As the need to

compete in international industrial markets became more pronounced,

culture became the way in which national identity was articulated by the

end of the 19th century, particularly for the middle classes.(65)

Accordingly, the transformation of art institutions (and the

establishment of new ones) also led to wider changes in educational

approach that affected architects, sculptors and the public. This will,

likewise, be discussed in more depth in my second article, set within

the specific context of the V&A’s founding objectives.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to many colleagues for their support during the preparation of this article, particularly those within the V&A’s Sculpture and Research departments. I would particularly like to thank Christopher Marsden (Senior Archivist, V&A) for inviting me to speak at his seminar on the history of the V&A’s buildings, as it gave me great feedback; Benedict Read for his willingness to discuss my ideas and review my work; Elaine Tierney (Managing Editor, V&A Online Journal) for her support and patience throughout, and Marjorie Trusted (Senior Curator of Sculpture, V&A) for her invaluable advice in the latter stages of completing this article.

Endnotes

1. I will use the term V&A to refer to the South Kensington Museum despite its not formally being named the Victoria and Albert Museum until 1899.

2. William Ewart, Report from the Select Committee on Arts and Manufactures: Together with the Minutes of Evidence, and Appendix (London: House of Commons Papers, 1835). See also William Ewart, Report from the Select Committee on Arts and their Connection with Manufactures; with the Minutes of Evidence, Appendix and Index (London: House of Commons Papers, 1836). A Government School of Design was chartered a few months after the Committee was adjourned in 1836 and founded at Somerset House in 1837, followed by Prince Albert becoming the President of the Society of Arts in 1843, founded in 1754 ‘for the Encouragement of Arts Manufactures and Commerce’.

3. Julius Bryant, Art and Design for All (London: V&A, 2012), 9. The Museum was set up in large part with the help of Prince Albert and Henry Cole who were keen to demonstrate Britain’s industrial and commercial supremacy and to propagate improvements in the quality of British Design.

4. John Physick, The Victoria & Albert Museum: The History of Its Building (London: V&A, 1982), 274-6.

5. The Illustrated London News, 27 June, 1857. The newspaper dubbed the temporary structure of The South Kensington Museum ‘the Brompton Boilers’ in response to a reference in The Builder, 16 April, 1956 that described the structure’s corrugated iron roofs as ‘a threefold monster boiler’.

6. Malcom Baker and Brenda Richardson, A Grand Design (London: V&A, 1998), 13. The Museum of Manufactures was founded at Marlborough House in 1852, renamed the Museum of Ornamental Art in 1853, opened as the South Kensington Museum in 1857 and finally named the V&A in 1899.

7. Physick, The Victoria & Albert Museum, 183-200. Webb’s design was modified in the light of finances, practical necessity and changing demands from the Department of Science and Art.

8. Aston Webb, Guide to the Victoria and Albert Museum, South Kensington (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1909), 6.

9. Eoin Martin, ‘Framing Victoria: Royal Portraiture and Architectural Sculpture in Victorian Britain’, Sculpture Journal 23. 2 (2014): 197–207.

10. Martina Droth, Jason Edwards and Michael Hatt, eds, Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention 1837-1901 (London: Yale University Press, 2014), 15-20.

11. For a detailed look at the range and proliferation of historic sculpture in Britain see The National Recording Project Series, Public Sculpture of Britain, published by Liverpool University Press. In relation to the City of London specifically see Philip Ward-Jackson, Public Sculpture of the City of London (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2003). See also Elizabeth Susan Darby, ‘Statues of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert: A Study in Commemorative and Portrait Statuary, 1837-1924’ (PhD thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, 1983).

12. The intellectual concept of Albertopolis derived from Prince Albert’s vision to build a complex in South Kensington, which would keep Britain at the peak of industrial world power specialising in art and science. It began with the ‘Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations’ in 1851, which yielded unpredicted profits of over £180,000 and continued with Albert’s belief that this should be spent on purchasing land within South Kensington for cultural and educational use.

13. Tori Smith, ‘“A Grand Work of Noble Conception”: The Victoria Memorial and Imperial London’ in Imperial Cities: Landscape, Display and Identity, ed. by David Gilbert and Felix Driver (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003), 21-39.

14. Susan Beattie, The New Sculpture (London: Yale University Press, 1983). As with all designations of movements, the New Sculpture label is used throughout my articles with a note of caution. Although it characterises the changing climate of sculpture in Victorian Britain, the term sometimes fails to capture the naturally diverse practice of its advocates, whose common aim was to reconsider the physical and material properties of the sculpted object.

15. Richard Fellows, Edwardian Architecture: Style and Technology (London: Lund Humphries Publishers Ltd, 1995) and Alastair Service, Edwardian Architecture and Its Origins (London: Architectural Press, 1975). The term Edwardian Baroque is considered a particularly retrospective period of British architectural history, since it is contemporary with what was arguably a more forward-looking style, Art Nouveau. However, it was the bridging style that helped see in modernism.

16. Deborah Cohen, Household Gods: The British and their Possessions (London: Yale University Press, 2006). Charlotte Gere, Artistic Circles: Design and Decoration in the Aesthetic Movement (London: V&A, 2010), 94. Galleries such as the Fine Art Society, established in 1876, were catering to the upper end of this new market.

17. Robert J. Morris and Richard Rodger, eds, The Victorian City: A Reader in British Urban History, 1830-1914 (London: Longman, 1993). See also Nancy Rose Marshall, City of Gold and Mud: Painting Victorian London (London: Yale University Press, 2012).

18. Asa Briggs, Victorian Cities (London: University of California Press, 1963), 324-5. See also Lynda Nead, Victorian Babylon: People, Streets and Images in Nineteenth-Century London (London: Yale University Press, 2000).

19. Simon Gunn, The Public Culture of the Victorian Middle Class: Ritual and Authority in the English Industrial City 1840-1914 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000). Benedict Read, Victorian Sculpture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982).

20. F. H. W. Sheppard, ed., 'Victoria and Albert Museum', in Survey of London: Volume 38, South Kensington Museums Area (London: London County Council, 1975), 97-102.

21. Barbara Bryant, Two Temple Place: A Perfect Gem of Late Victorian Art, Architecture and Design (London: Bulldog Trust, 2013), 37-9.

22. Yves Koopmans, Fixed and Chiselled: Sculpture in Architecture 1840-1940 (Rotterdam: NA1 Uitgevers, 1994) and Karen Lang, ‘Monumental Unease: Monuments and the Making of National Identity in Germany’, in Imagining Modern German Culture 1889-1910, ed. by Françoise Foster-Hahn, Studies in the History of Art, no. 53, (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1997), 275-99.

23. Penelope Curtis, Sculpture 1900-1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 8.

24. See The National Recording Project Series, Public Sculpture of Britain published by Liverpool University Press, notably: Philip Ward-Jackson, Public Sculpture of Historic Westminster: Volume 1 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2012); Ray McKenzie, Public Sculpture of Glasgow (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2002); Terry Cavanagh, Public Sculpture of Liverpool (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1997).

25. Curtis, Sculpture 1900-1945, 5-9.

26. Sidney Hutchison, The History of the Royal Academy, 1768-1968 (New York: Chapman and Hall, 1968). The Royal Academy of Arts was founded in 1768 with a mission to cultivate and improve the arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture in Britain through education and exhibition.

27. University of Glasgow History of Art and HATII, ‘“The Glasgow School of Art”: Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain & Ireland 1851-1951’, online database 2011, http://sculpture.gla.ac.uk/view/organization.php?id=msib6_1205768197

28. See the National Recording Project for the Public Monuments and Sculpture Association (PMSA), http://www.pmsa.org.uk/pmsa-database/5644/.

29. Gary Nisbet, ‘John Thomas (1813-1862)’, Glasgow - City of Sculpture, http://www.glasgowsculpture.com/pg_biography.php?sub=thomas_j. W. B. Gingell and T. R. Lysaght were the building’s architects and the sculptor John Thomas (1813-62) was the supervising carver employed to oversee the bank’s decoration. His large workshop of architectural sculptors carried out the work. The adornment was intended to emphasise the wealth, and therefore financial stability, of the bank, which in fact collapsed 20 years later in 1878. See also The Army and Navy Club in London’s Pall Mall, built in 1850 from the designs of Parnell and Smith.

30. F. H. W. Sheppard, ed., Survey of London: Volumes 29 and 30: St James Westminster, Part 1 (London: London County Council, 1960), 180-86, available online at http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols29-30/pt1. For an illustration of the Carlton Club prior to its wartime destruction, see The Dictionary of Victorian London, http://www.victorianlondon.org/entertainment/carltonclub.htm. Another similar London example is The Army and Navy Club, built in Pall Mall in 1850 by Parnell and Smith.

31. British Architect, Friday 17 April, 1. 16 (1874): 241.

32. Droth, Edwards and Hatt, eds, Sculpture Victorious, 12-13.

33. William Rossetti, ‘British Sculpture: Its Condition and Prospects’, Fraser’s Magazine for Town and Country, 63 (1861): 493-505.

34. British Architect, Friday 17 April, 1. 16 (1874): 241.

35. Ann Compton, ‘“Art Workers”: Education and Professional Advancement in Sculpture and the Stone Trades c.1850-1900’ Sculpture Journal 21. 2 (2012), 119-30.

36. Martina Droth, ‘The Ethics of Making: Craft and English Sculptural Aesthetics c.1851-1900’, Journal of Design History 17. 3 (2004): 223-4.

37. Patricia Mainardi, The End of the Salon: Art and the State in the Early Third Republic (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993). Rodin was one of the unidentified sculptors who worked on the Hotel de Ville.

38. Carl Milles, Episodes from my Life (Stockholm: Ehrenblad Editions, 1991). These anecdotes tell of Milles's struggles for recognition, and his work and years in Paris, America and Italy.

39. David Getsy, Body Doubles: Sculpture in Britain, 1877-1905 (London: Yale University Press, 2004), 2.

40. Edmund Gosse, ‘The New Sculpture: 1879-1894’, Art Journal 56 (1894): 138-42, 199-203, 277-82, 306-11.

41. Hermione Hobhouse, ed., 'Architectural sculpture and decorative treatment', in Survey of London Monograph 17 (London: County Hall, 1991), 57-69.

42. Michael Brooks, John Ruskin and Victorian Architecture (London: Rutgers University Press, 1936), 299-313. The Art Workers’ Guild for example, included many of the best artists and architects of the time who wished to establish new links between art and life.

43. Fellows, Edwardian Architecture, 7.

44. Bridget Cherry and Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England: London 3: North West (London: Penguin, 1991), 495.

45. Robert Macleod, Style and Society: Architectural Ideology in Britain 1835-1914 (London: Riba Enterprises, 1971).

46. Fellows, Edwardian Architecture, 13-15.

47. Lara Platman, Art Workers Guild 125 Years: Craftspeople at Work Today (London: Unicorn Press, 2009). See also: Art Worker’s Guild, http://www.artworkersguild.org/about-us/history/.

48. Curtis, Sculpture 1900-1945, 19.

49. P. Rathbone, ‘Architecture as a Necessary Element in National Economy’ (paper read to the Liverpool Architectural Society, 3 December 1894).

50. R.I.B.A Journal, 1 (1893): 4-6.

51. John Belcher, Essentials in Architecture: An Analysis of the Principles and Qualities to be looked for in Buildings (London: B. T. Batsford, 1907), 45.

52. Belcher, Essentials in Architecture, 7.

53. Christopher Crouch, Design Culture in Liverpool, 1880-1914: The Origins of the Liverpool School (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2002), 69.

54. Crouch, Design Culture in Liverpool, 70.

55. Terry Friedman et al, The Alliance of Sculpture and Architecture: Hamo Thornycroft, John Belcher and the Institute of the Chartered Accountants Building (Leeds: Henry Moore Sculpture Trust, 1993), 5.

56. Henry Cole and Richard Redgrave, eds, The Journal of Design and Manufactures, vols 1-6 (London: Chapman and Hall, 1849-52). Six volumes of the journal were published between 1849 and 1852. Its main aim was to call for a greater co-operation between art and industry, encouraging designers to reach a balance between utility and ornament. Written at a time when standards in Victorian design were disappointing, especially in mass manufactured machine products, the journal is a manifestation of the period's wider concern about the relationship between decoration and function. This was also being witnessed abroad slightly earlier in France. See Claire Jones, Sculptors and Design Reform in France, 1848 to 1895 (Surrey: Ashgate, 2014).

57. For a brief contemporary survey of Academies, Schools, and Galleries in the Victorian era see ‘Victorian Art Institutions: A Contemporary Survey of Academies, Schools, and Galleries’, Victorian Web, http://www.victorianweb.org/art/institutions/1.html. For specific references see Jonathan M Woodham, ‘Brighton School of Art - the Victorian age to the twentieth century’, University of Brighton Faculty of Arts, http://arts.brighton.ac.uk/faculty-of-arts-brighton/alumni-and-associates/the-history-of-arts-education-in-brighton/brighton-school-of-art---the-victorian-age-to-the-twentieth-century. Cole was far more than an educational bureaucrat, having been a Royal Society of Arts design prize-winner and a moving force behind the Great Exhibition of All Nations held in the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park in 1851.

58. The Times, 10 May, 1893: 23.

59. For the history of Lloyd’s Shipping Register and George Frampton’s role on the building designed by Thomas Collcutt see ‘Lloyd’s Register in London: The Collcutt and Rogers Buildings’, ed. by Kathy Davis, Lloyds Register Group Services, http://www.lr.org/en/_images/213-35624_LR_in_London.pdf

60. Sheppard, 'Victoria and Albert Museum', 118.

61. Pieter Singelenberg, H.P. Berlage Idea and Style: The Quest for Modern Architecture (Utrecht: Haentjens Dekker & Gumbert, 1972). The same two artists had previously collaborated in 1895 on the Netherlands Insurance Company at The Hague.

62. Denise Basdevant, Bourdelle et le Theatre des Champs-Elysees (Paris: Hachette, 1982).

63. Curtis, Sculpture 1900-1945, 14.

64. Getsy, Body Doubles: Sculpture in Britain, 1.

65. Alexandra Ward, ‘Archeology, Heritage and Identity: The Creation and Development of a National Museum in Wales’, (Michigan: ProQuest, 2008), 13-19. Ward’s published PhD thesis examines 19th-century museums as cultural producers. Albeit slightly later in the period see also: Catherine Moriarty, ‘Joseph Emberton: The Architecture of Display’, Palant House Magazine 34 (2015).

Issue No. 7 Summer 2015

- Editorial

- An Unusual Embroidery of Mary Magdalene

- Printed Sources for a South German Games Board

- ‘Sawney’s Defence’: Anti-Catholicism, Consumption and Performance in 18th-Century Britain

- A Weft-Beater from Niya: Making a Case for the Local Production of Carpets in Ancient Cadhota (2nd to mid-4th century CE)

- Out of the Shadows: The Façade and Decorative Sculpture of the Victoria and Albert Museum, Part 1

- Gestures, Ritual & Play: Interview with Liam O’Connor

- Contributors