Conservation Journal

Spring 2011 Issue 59

Removing and re-attaching paper labels

Juanita Navarro

Senior Ceramics and Glass Conservator

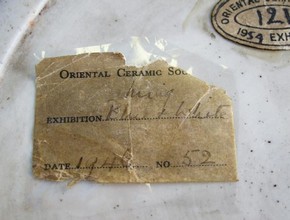

Figure 1 - Paper labels on the back of a Limoges painted enamel, showing Magniac and Salting Collections labels and lot number in Spitzer collection sale. Photography by Juanita Navarro

Labels attached to ceramic and glass objects (including enamels) are an integral part of the object because of the historical information they contain, such as provenance (Figure 1). Whilst labels can be made from parchment or plastic, paper labels are by far the most common. Their adhesives may be water-sensitive (e.g. plant gums or animal glue, such as gelatine) or organic solvent-sensitive (e.g. self-adhesive or pressure sensitive). Another component is the written or printed information whose medium may be solvent-sensitive (e.g. water-soluble inks). All these elements must be considered during the object’s treatment.

It may be necessary to remove an existing paper label if, for instance, the label was torn when the object broke or if it is causing damage to the object. Such is the case when a paper label with water-sensitive adhesive (both materials absorb and retain humidity) is attached to chemically unstable glass (vulnerable to degradation by humidity); this can lead to flaking and pitting of the glass. Where feasible, the label should be re-attached as close as possible to the original location and with as little unwelcome change, especially without any loss of precious information. If the label cannot be re-attached, it should be stored with the object’s documentation. When there is possible loss of historical evidence during treatment, a paper conservator should be consulted.

The use of liquid water or organic solvents to remove paper labels may cause damage to the paper and written media, mobilise soluble salts in porous ceramics and create other problems. The following technique was designed to enable the conservator to remove paper labels, carry out repairs and re-attach the labels. Localised controllable humidification, i.e. transference of water vapour rather than liquid water, is applied by placing a specific sequence of materials arranged in layers, known as the ‘sandwich’ (1) (2) over the label.

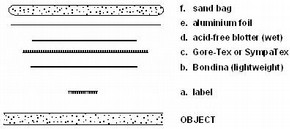

Figure 2 - The 'sandwich' layers used to humidify a paper label

The crucial layer in the sandwich (Figure 2) is the water-vapour permeable membrane, such as Gore-Tex® or SympaTex®. Gore-Tex is a micro porous membrane of expanded polytetrafluoroethene (PTFE), similar to Teflon®, where the vapour passes through 1.4 billion pores per square centimetre, whereas SympaTex is a non-porous membrane, which allows the vapour to pass through built-in hydrophilic polyether ester copolymer blocks.

Water vapour passes from the acid-free blotter saturated with water through the membrane to the dry label and humidifies the paper and adhesive. The area of the wet blotter is smaller than the membrane to prevent liquid water seeping onto the paper or object. When the sandwich is used correctly there is no undesirable build-up of moisture that would allow inks, adhesives or existing soiling to mobilise. Flexible aluminium foil covers the sandwich and prevents evaporation, while the small sand bag on top ensures gentle pressure and good contact throughout. The adhesive on a label will usually be safely humidified and released within 20-30 minutes and may then be gently lifted with a small spatula. The label is allowed to dry flat between layers of lightweight Bondina® (non-woven polyester fabric), a dry blotter and sand bag. If the label needs further conservation treatment, a paper conservator should be consulted.

A suitable adhesive to re-attach the labels will not mobilize the material on the label, consolidate the paper or stain porous ceramic bodies. It will have good reversibility properties as well as good adhesion to ceramics and glass. The chosen adhesive is a thin film made from isinglass, the generic name for fish glue made from the swim bladder of several fish. Sturgeon isinglass is very pure with high molecular weight. In practice, a smaller amount of this adhesive will have proportionally more sticking potential than other animal glues. A glue solution is cast as a thin film which can be stored indefinitely in dry conditions. To re-attach the label, a small piece of film is placed under the label (Figure 3) and the sandwich described earlier built above it (Figure 4). The isinglass readily becomes tacky with the water vapour in order to bond the label to the surface. After suitable humidification, the sandwich is removed, final adjustments are made and the label is allowed to dry with a dry blotter and sandbag on top. When a self-adhesive label is still in good condition, the label may simply be pressed back in place.

Figure 3 - Re-attaching the label: dry isinglass film visible under the under the label. Another label is visible on top right corner. Photography by Juanita Navarro

Figure 4 - First layers of the sandwich over the label: Bondina, GoreTex and wet acid-free blotter. Photography by Juanita Navarro

The reasons for removing an historic label should be justified as part of the conservation plan. When removal is unavoidable, the long-term survival of the label and the information contained must be ensured. Ideally this process will be carried out by a conservator who is familiar with paper and the materials of the object, but this is often not the case. It was this difficulty that prompted the investigation on how to remove the label while minimising the risk of damage and the amount of change. Finding that isinglass film was the most fitting adhesive for the purpose concluded the long search for a technique that ceramics and glass conservators can use with confidence when a paper conservator is not available. When the label needs further treatment after removal, a paper conservator should definitely be consulted.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to: Alison Richmond from whom I first heard about permeable membranes when she worked at the V&A, the late Merryl Huxtable for mentioning isinglass, and their colleagues in Paper Conservation for their generosity with information and sample materials, Victoria Oakley and C. Velson Horie for comments.

References

(1) Navarro, J., ‘Removing Paper Labels from Ceramics and Glass’, The Conservator 21, 1997, pp 21-27.

(2) Navarro, J., ‘Reattaching Paper Labels to Ceramics and Glass’, Glass and Ceramics Conservation 2010, ed. Hannelore Roemich, ICOM Committee for Conservation and The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, NY, October 2010, pp 93-99. [Please note: these are the preprints of the Interim meeting of the ICOM-CC Working Group Glass & Ceramics]

Spring 2011 Issue 59

- Editorial

- Keep Your Hair On - The development of conservation friendly wigs

- ‘X’ Marks the Spot: The conservation and correction of a Carlo Bugatti Chair

- Removing and re-attaching paper labels

- Will it stand? Morris and Co. wallpaper stand book

- Melting pot: Conserving wax objects in textile conservation

- The effects of fingerprints on silver

- The conservation of John Constable’s six foot sketches at the V&A

- The show must go on: Touring textile and costume objects with hazardous substances

- Dust to dust. Access to access.

- An update on lasers in sculpture conservation

- An approach to conserving study collections

- I’m always touched (by your presence dear)

- The contemporary art of documentation

- The Popart project

- V&A launches new National Conservation Diploma and the Conservator Development Programme

- Editorial board & Disclaimer

- Printer friendly version