Conservation Journal

Autumn 2004 Issue 48

Nasrid plasterwork: symbolism, materials & techniques

As part of the display for the new Architecture Gallery, and to represent the art in architecture within the Spanish Islamic style, five fragments of plasterwork from the Alhambra Palace of Granada, Spain were selected from the V&A Collection. These fragments date from the fourteenth century when Nasrid art was at its most splendid. This article, based on the analysis 1 of samples taken from mortars and paint layers and on observations during conservation treatment, forms an introduction to traditional materials and techniques used in Nasrid plasterwork as well as explaining their style and symbolism.

The first Islamic invasion of the Iberian peninsula occurred in 711 AD; three years later almost the whole Iberian territory was under the rule of Berber troops. The occupation lasted almost eight hundred years, giving place to one of the most extraordinary periods of art and culture in medieval Europe. Al-Andalus, the name given to the occupied Iberian territories, was slowly re-conquered by the Christian Kings through the centuries. However it was not until 1492 that the Catholic Kings finally conquered the last standing Muslim kingdom in Europe, Granada, ruled at the time by the Nasrid dynasty. Muhammad ibn Nasr I was the founder of this dynasty, which ruled this kingdom from 1238-1492. They originated the most monumental, sophisticated and lavish period within Spanish Islamic art, making Granada the artistic centre of North Africa (Marinid Art) and the Iberian Christian Kingdoms (Mudéjar Art).

The best example of Nasrid art is the Royal residence of the Alhambra (Al-hamra = the red), a world of luxury and comfort, obtained through a combination of splendid architecture and formally designed gardens with numerous fountains and pools. The main architectural features within the buildings are ceramic mosaics, plasterwork and carved wooden ceilings all profusely decorated, reflecting the Islamic tendency to cover all surfaces with complex ornaments (Horror Vacui), and blended together with subtle light effects, carpets, curtains and hanging textiles.

Nasrid plasterwork covers almost every single surface of walls, arches, vaults and ceilings, gaining an almost textile quality through their intricate ornament and vibrant palette of colours. Its almost overwhelming appearance is the result of the interconnection and superimposition of different ornamental elements: calligraphic inscriptions, geometric lazo, ataurique and mocárabes.

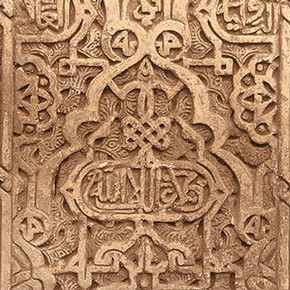

The calligraphic inscriptions found in the Alhambra correspond to two different styles: Kufic (dry style) and Nashkhid-Thuluth (cursive style). Kufic calligraphy, which usually refers to quotations from the Holy Qur'an, consists of a combination of square and angular lines with bold circular forms. When applied to plasterwork it tends to form part of the decoration becoming almost illegible. In figure 1, the kufic inscription at the bottom of the panel elongates and transforms its characters into decoration. References to some invocations as the 'baraka' (blessing), with its elongated "kāf" and "tā ' marbūt' a" letters, appear in the centre and corners of the panel. And on top of the central baraka the letter "nūn" makes an invocation to happiness (yumn).

Nashkid-Thuluth calligraphy is a more elegant style used for describing the function of the rooms or as a reference to poetic quotations. In later periods, the Nasrid used it as a vehicle for their propagandistic aims, displaying their dynastic motto 'Wa la ghalib ila Ala' ('There is no conqueror but God') in key locations of the design (bottom centre of figure 1).

Geometric lazo: these geometric compositions, so popular in Islamic art, appear in Granada with such distinctive, accurate and rigorous design that they form a western school within Muslim art. Creations peculiar to Nasrid art are the square grid, the geometric lazo of eight and the eight pointed star. These stars were the central point for bigger compositions called 'ruedas' (wheels) where the lazo creates a geometric composition around the star (figure 2).

Ataurique (al-tawrīq = leaves, foliage, flora) is the name given to Nasrid floral and vegetal decorations. These patterns come from classic decorative elements, such as fruits, flowers and acanthus leaves, which evolved into more typical Hispano-Muslim abstractions. These are found as free decorations on arches and windows, or filling spaces created by the geometric lazo (figure 2) and the calligraphic inscriptions (figure 1). During the time of Muhammad V (1354) more themes and variations appear: complex palm leaves (background of figure 1), shells (symbol of the origin of life, figure 3), peppercorns, pine cones, and for the first time, they begin to appear intertwined with calligraphic inscriptions.

Mocárabe is a type of ornament built up from vertical prisms applied one over another. They would be joined in multiple different arrays resembling stalactites, probably relating to the cave where the prophet Mohammed received the inspiration for the Qur'an. The mocárabe is found located on capitals (figure 3) and friezes, expanding to windows, arches and vaults at the time of Muhammad V. Nasrid mocárabes are characterised by their immense variety of geometrical shapes and precise mathematical proportions, making them unique in western Islam.

The main component of Nasrid plasterwork is gypsum (hydrated calcium sulphate). Retardants such as salts, glue or calcium carbonate were added to slow the setting and permit carving while panels were still damp. Sometimes the back would be reinforced with a rougher gypsum plaster containing sand and fibres. On the samples taken from the mortars, only gypsum was found. As a retardant, salts or glue may have been used. No trace of calcium carbonate was found.

During the first period of Nasrid Art (1232-1314) the carving process took place in situ with the 'naqch hadîda' technique (sculpture with iron tools). The gypsum plaster was applied and then carved, following the design previously outlined with dry point. The ornamental motifs were then carved at different levels with the most important on top. To finish off, several white washes of lime or gypsum were applied to soften the edges of the carving and blur the transition between light and shadows. Only gypsum was found on figures 1 and 3.

With Muhammad III (1302) the technique became more standardised: moulds began to be used. The design was drawn and cut in sections in order to make moulds on wood or plaster. The casts obtained would be set in place while damp with dabs of clay and sealed in with a gesso slurry. Finally the whitewash and the polychromy, when required, were applied. All the fragments studied were cast.

Mocárabes were produced following a more elaborate process depending on whether the design was intended for a capital, frieze, arch or vault. The number and variety of prisms (jairas) required for the design were calculated. The variety of cuts on the ends of the prisms created different geometrical shapes, called 'adarajas'. The cut prisms were then joined with liquid gesso into rectangular sections (medinas), reinforced with a rougher plaster mixture and set in the final destination with clay (figure 3).

Nasrid masons loved playing with light and colour effects in their plasterwork designs. Some panels were simply whitewashed (figures 1 and 3), while others were richly painted, using high quality pigments in a wide range of colours: red, blue, green, purple and black combined with gold and silver leaf. The painting technique, as seen in figure 2, was extremely delicate and precise: plain background colours, silver or gold leaf on the high relief, and carefully executed sgraffito and fine painted miniatures creating exquisite effects.

In the case of the fragment in figure 2, traditional pigments were found. The high degree of fluorescence obtained with the Raman analysis in all samples could be due to the presence of an aged binding medium, probably gum arabic or egg. Two of the most significant pigments traced are: red vermilion, probably produced by the so-called dry process, used in China in antiquity and thought to have been introduced in the West by the Arabs; and blue lazurite, which is obtained from lapis lazuli. This mineral, mainly extracted in Afghanistan, was so expensive at the time that its value was equivalent to gold, reflecting once more the luxury of this polychromy and the sophistication of Nasrid plasterwork. Traces of other materials were found, but further analysis of these is required.

References

1. Burgio, Lucia. 04-27-lb Alhambra - Microscopy analysis of Hispano-Moresque samples from the Alhambra, V&A Science Report, June 2004.

Further reading

Puertas Fernández, A. 'The Alhambra' Vol. 1., Saqi Books, 1997.

García Bueno, A., and Medina Flórez V. J., The Nasrid Plasterwork at 'qubba Dar al-Manjara l-kubra' in Granada: Characterisation of materials and techniques, Journal of Cultural Heritage 5, 2004.

Autumn 2004 Issue 48

- Editorial

- A souvenir from Guangzhou

- Conservation Department seminar report

- An away day to Belgium: Washing tapestries

- Yomeimon of Toshogu

- Nasrid plasterwork: symbolism, materials & techniques

- Mixed media object: large and fragile structure

- Planning and estimating

- RCA/V&A Postgraduate Conservation Programme

- Printer friendly version