Conservation Journal

July 1996 Issue 20

The Hole in the Ground - Sculpture Conservation's New Studio

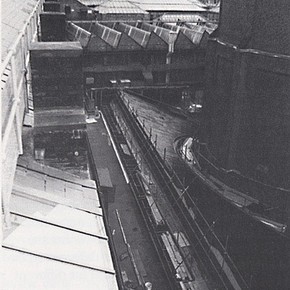

Figure 1. Site of the New Sculpture Studio before construction. Photography by V&A Photographic Studio (click image for larger version)

We are in our remarkable new studio at last. It is strange, but it seems as if we have been here for ever. Somehow we have already filled the space with large objects and even other people. Metalwork Conservation has already used our extraction booth for lacquering a large bronze and cleaning a large silver wine cooler. The new studio is miraculous compared to the accommodation that Sculpture Conservation has had previously.

In the early 70s, sculpture was conserved on the top floor of the conservation block. Ken Hemple, who was then head of the section, used to have all the marble busts carried up three flights of concrete stairs to be cleaned. There was a ground floor shed occupied by two masons, Jim Ellis and Bob Barns (whose father had helped build the Museum). Legend has it that Bob Barns cooked his breakfast at the end of the room each day and did all the large masonry jobs in the same room - attitudes about health and safety have changed a little since then! As a young conservator, John Larson began to work in this room because of the easier access. Later, as Acting Head, he brought the studio down to the quadrangle behind the Gamble Room. The studio was long and thin and slightly raised from the surrounding ground. All trolleys had to go up a ramp which was cursed by object handlers for two decades. It was at this point that I joined the Museum and I worked for 15 years in the 'pickling shed' as it was referred to. I have never been certain what was pickled, maybe someone knows better. There was however a lead lined sink at this time that stretched the whole length of the room.

Figure 2. The organic and polychrome room. Photography by V&A Photographic Studio (click image for larger version)

An extra room for polychrome work was obtained by converting a nearby gentleman's lavatory. The organic and polychrome room was very awkward to work in. The roof sloped to a low point so that only a small part of the floor space could be used for objects on easels. The environment of the room was impossible to control as the wall joining it to the stained glass studio was difficult to seal. At the rear of the pickling shed there was an open yard which was later roofed over with clear plastic and also a small shed with extremely thick walls which had meat hooks in the ceiling. This meat store was used for the storage of materials and equipment. Later, a wooden shed was built to allow air abrasive and other hazardous conservation activities to be carried out. None of the rooms were interconnected and it was obligatory that sculpture conservators were waterproof.

From the first murmurs of the building of a new studio, we began to think very seriously about the design and what we had seen of other workshops. Fortunately a courier trip to New York came at the right moment and I met Lisa Pilosi who had worked in our studio. She showed me round the newly refurbished conservation department at the Metropolitan Museum. She also introduced me to Jack Soultanian, Head of Sculpture. Two things immediately caught my attention: the perfect quality of light in the sculpture studio and the adjustable tables in the furniture conservation rooms.

I went to Liverpool to look at the new studio in the Great Western Railway building which houses sculpture conservation for the National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside which was planned by John Larson and Anne Brodrick. The rooms were set out for large objects on the ground floor with good access and cranes over the studio. The height was good but the light was not as good as my ideal would have been. There was a division for air abrasion and other unpleasant conservation processes. Work on small objects and microscope work were carried out on the first floor with access to a goods lift. The crane interested me as it was a double beam with four independent lifting points. This would allow heavy objects to be manipulated from four points with great accuracy. I have visited other studios when I can as it has been a general interest of mine for a long time: the Tate Gallery sculpture studio has the space, the light and the height of which I have always been envious whenever I have visited.

Figure 3. The roof over Sculpture Conservation showing the Gamble Room arc (click image for larger version)

I felt that we should approach our new building from the ideal. But what was the ideal for this sculpture studio? It is a question not only of the variety of materials, but also the sheer scale of the objects in the V&A's collection. On many occasions, I have looked at an object and immediately started to look for somewhere accessible to work on it. The variety of the materials and conservation techniques dictate a minimum of three rooms in the studio, excluding an office, storage areas and an X-ray room. Each of these rooms are required for different types of objects and for different processes.

The organic and polychrome room needs to be small enough to control the environment but large enough to take some of the larger wooden objects such as the life size crucifix which is in the sculpture collection. There is a need for a room for the wet, the dusty and the smelly jobs, a position for the stone saw and somewhere to lift the heavy objects. We also required a large, adaptable room where most of the conservation could be carried out, big enough for the occasional use of an 'A' frame crane. Each of these rooms should be well lit and have good access and should be high enough to be able to take a loaded stacker with its mast raised. One of these rooms should have total blackout facilities so that uv photography can be carried out.

The work that we undertake, includes technical investigation which has always been restricted by the access both for X-ray and for uv photography. A room that would take a 1.5m3 object and that had a more powerful X-ray head was a priority.

Figure 4. The new Sculpture Conservation Studio. Photography by V&A Photographic Studio (click mage for larger version)

The site for the proposed building was the one I knew well - the pickling shed and the stained glass studio in the North Yard. These would be demolished, giving a clear site (Figure 1). It has one drawback. It is surrounded on all sides by high walls. The work area would have to be top lit by daylight but there would be little problem from solar gain. The planning had the benefit of a clear site without the conflict of other studios but it is still troublesome because the Gamble room impinges on the site in a big arc across one of the corners of the rectangle (Figure 3). The architects have managed the design very well in a difficult area.Many of the ideals have been achieved in the new studio. The light in the studio is adequate except for the polychrome area where the skylights are a little on the small side. The extraction room is already proving to be very useful and keeps the fumes away from the rest of the studio. The access is very good and the ceiling height is correct. The only really annoying thing is a strange vertical ladder to a storage area that is impossible to use. The size of the crane room and the storage area could both have been larger, but space is a constraint in central London. The polychrome room needs climate control, but that will happen. The crane and the X-ray equipment are coming soon. The studio has a very pleasant ambience about it and is extremely practical.

I must thank all the people concerned who have achieved this work space. The design process has been a little traumatic at times but the result is most certainly good.

July 1996 Issue 20

- Editorial

- Introduction

- The Research and Conservation of Art Centre

- The Victoria and Albert Museum, Royal College of Art Building Project

- Designing the Interior

- Textile Conservation Studio

- The Michael Snow Laboratory

- The Hole in the Ground - Sculpture Conservation's New Studio

- New Working Practices - Could we do it like that?

- Time for a Change - The New Paper Conservation Studios

- Book Conservation Studio

- Printer Friendly Version