Closed Exhibition - Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty

Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty - About the Exhibition

Portrait of Alexander McQueen, 1997 photographed by Marc Hom. © Marc Hom/Trunk Archive

14 March - 2 August 2015

'I'm a romantic schizophrenic'

- Lee Alexander McQueen (1969 - 2010)

Alexander McQueen's dashing creativity was expressed through the technical artistry of his designs and the dramatic intensity of his fashion shows. Drawing on avant-garde installation and performance art, these were also emphatically autobiographical. McQueen fearlessly challenged the conventions of fashion. Rare among designers, he saw beyond clothing's physical constraints to its conceptual and imaginative possibilities.

Over and again, McQueen's spectacular catwalk presentations unleashed powerful feelings as compelling sources of aesthetic experience. In the spirit of Romanticism, unfettered emotionalism sustained his profound appreciation of beauty. Evoking the feelings of shock and awe associated with the Sublime, his dark imaginings elicited an uneasy pleasure that merged wonder and terror, incredulity and revulsion.

McQueen's romantic sensibility propelled his creativity and advanced his fashion in directions both unimagined and unprecedented. His individualistic and defiant vision was augmented by an acute sense of time and place, and a preoccupation with the exotic and the untamed. Filtered through a powerful modernity McQueen's work was, above all, driven by his fascination with the beauty and savagery of the natural world.

London

'You take inspiration from the street, with the trousers so low. You don't need to go to India, you can find it in places like Bethnal Green or down Brick Lane. It's everywhere'

- Alexander McQueen

©Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Working with a small, closely knit team and a very low budget, he produced a series of enthralling and provocative shows set in gritty, industrial locations across the capital. McQueen’s characteristic blend of tradition and subversion was evident from the outset with ‘Bumster’ trousers, sharp frock coats, corroded fabrics, slashed leather and shredded, flesh-revealing lace. He recalled, ‘There was so much repression in London fashion. It had to be livened up.’'London's where I grew up. It's where my heart is and where I get my inspiration'

- Alexander McQueen

Savage Mind

‘You’ve got to know the rules to break them. That’s what I’m here for, to demolish the rules but to keep the tradition.’

- Alexander McQueen

©Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Alexander McQueen consistently promoted freedom of thought and expression, and championed the authority of the imagination. In this, he was an exemplar of the Romantic individual, the hero-artist who staunchly followed the dictates of his inspiration. 'What I am trying to bring to fashion is a sort of originality', he once commented.

McQueen expressed this originality most fundamentally through his methods of cutting and construction. These were both innovatory and revolutionary. He was such an assured designer that his forms and silhouettes were established from his earliest collections, and remained relatively consistent throughout his career. referring to his early training on Savile Row in London, McQueen said, 'Everything I do is based on tailoring'.

©Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This approach to fashion, however, combined the precision and traditions of tailoring and pattern making with the improvisations of draping and dressmaking, an approach that became more refined after his tenure as creative director of Givenchy in Paris. It is this way of working, at once rigorous and impulsive, disciplined and unconstrained, that underlies McQueen's singularity and inimitability.

'I want to be the purveyor of a certain silhouette or a way of cutting, so that when I'm dead and gone people will know that the twenty-first century was started by Alexander McQueen.'

- Alexander McQueen

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

A Gothic Mind

‘People find my things sometimes aggressive. But I don’t see it as aggressive. I see it as romantic, dealing with a dark side of personality.’

- Alexander McQueen

One of the defining features of Alexander McQueen’s collections was their historicism. While McQueen’s historical references were far- reaching, he was particularly inspired by the nineteenth century, drawing especially on the Victorian Gothic. ‘There’s something kind of Edgar Allan Poe,’ he once observed, ‘kind of deep and kind of melancholic about my collections.’

Indeed, the 'shadowy fancies' that Poe writes about in The Fall of the House of Usher (1839) are often vividly present in McQueen's collections. Like the Victorian Gothic, which combines elements of horror and romance, McQueen’s collections often reflected paradoxical relationships such as life and death, lightness and darkness, melancholy and beauty.

©Victoria and Albert Museum, London

‘There has to be a sinister aspect, whether it’s melancholy or sadomasochist. I think everyone has a deep sexuality, and sometimes it’s good to use a little of it – and sometimes a lot of it – like a masquerade.’

- Alexander McQueen

Romantic Primitivism

'What I do is look at ancient African tribes, and the way they dress. There's a lot of tribalism in the collections.'Throughout his career, Alexander McQueen frequently returned to the theme of primitivism, which drew upon the fantasy of the noble savage living in harmony with the natural world. Eshu (Autumn/Winter 2000) was inspired by one of the most well-known deities of Yoruba mythology. Using materials such as hair, beads, latex and mud, McQueen imbued the garments with fetishistic qualities. It’s a Jungle Out There (Autumn/Winter 1997–98) was based on the theme of the Thomson’s Gazelle. The collection was a meditation on the dynamics of power, in particular the dialectical relationship between predator and prey.

- Alexander McQueen

©Victoria and Albert Museum, London

McQueen’s reflections on primitivism were frequently represented in paradoxical combinations, contrasting modern and primitive, civilized and uncivilized. The storyline of Irere (Spring/Summer 2003) involved a shipwreck at sea and was peopled with pirates, conquistadors and Amazonian Indians. Typically, McQueen’s narrative glorified the state of nature and tipped the moral balance in favour of the ‘natural man’ or ‘nature’s gentleman’, unfettered by the artificial constructs of civilization.

‘Animals fascinate me because you can find a force, an energy, a fear that also exists in sex.’

- Alexander McQueen

Romantic Nationalism

'The reason I'm patriotic about Scotland is because I think it's been dealt a really hard hand. It's marketed the world over as haggis and bagpipes. But no one ever puts anything back into it.'

- Alexander McQueen

©Victoria and Albert Museum, London

©Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Despite these heartfelt declarations of his Scottish national identity, McQueen also had a deep interest in the history of England. This was most apparent, perhaps, in The Girl Who Lived in the Tree (Autumn/Winter 2008), inspired by an elm tree in the garden of McQueen’s country home near Fairlight Cove in East Sussex. Influenced by the British Empire, and drawing on a recent trip to India it was one of McQueen’s most romantically nationalistic collections, albeit heavily tinged with irony and pastiche.

‘As a place for inspiration Britain is the best in the world. You’re inspired by the anarchy in the country.’

- Alexander McQueen

Cabinet of Curiosities

‘I find beauty in the grotesque, like most artists. I have to force people to look at things.’

- Alexander McQueen

The emotional intensity of McQueen’s catwalk presentations was frequently the consequence of the interplay between dialectical oppositions. The relationship between victim and aggressor was especially apparent, particularly in the accessories. He once remarked, ‘I like the accessory for its sadomasochistic aspect.’

©Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This position was strikingly evident in the exhibition’s 'Cabinet of Curiosities', which focused on atavistic and fetishistic paraphernalia produced by McQueen in collaboration with a number of accessory designers, including the milliner Philip Treacy and the jeweler Shaun Leane. The 'Cabinet' also included show pieces, one-off creations made for the catwalk but not intended for production. McQueen used all kinds of materials, commissioning skilled wood carvers, leather workers, prosthetists, glass soecialists, embroiderers and plumassiers (feather workers) to help realise his vision.

©Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Romantic Exoticism

'As a designer you go through every nook and cranny to find inspiration. I get more inspiration from the personality of a region than the actual ethnic origin I think it's more important for the evolution of any design.'

- Alexander McQueen

©Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Alexander McQueen’s romantic sensibilities expanded his imaginary horizons not only temporally but also spatially. As it had been for artists and writers of the Romantic Movement, the lure of the exotic was a central theme in McQueen’s collections. His exoticism was wide-ranging. Africa, China, India and Turkey were all places that sparked his imagination. Japan was particularly significant, both thematically and stylistically. The kimono, especially, was a garment that the designer endlessly reconfigured in his collections.

Indeed, McQueen's exoticism was often a form of creative translation. Remarking on the direction of his fashions, he once commented, 'My work will be about taking elements of traditional embroidery, filigree and craftsmanship from countries all over the world. I will explore their crafts, patterns and materials and interpret them in my own way.'

©Victoria and Albert Museum, London

But as with many of his themes, McQueen’s exoticism often expressed itself in contrasting opposites. This was the case with It’s Only a Game (Spring/Summer 2005), a show staged as a chess game inspired by a scene in the film Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (2001), which pitched the East (Japan) against the West (America).

'Fashion can be really racist, looking at the clothes of other cultures as costumes. That's mundane and it's old hat. Let's break down some barriers.'

- Alexander McQueen

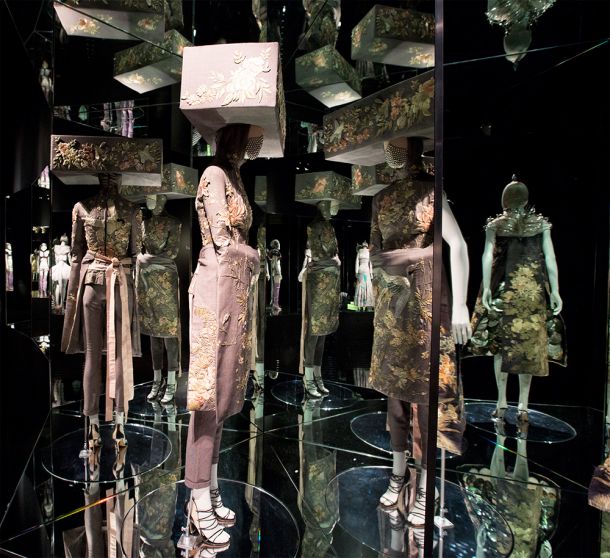

Voss

‘It was about trying to trap something that wasn’t conventionally beautiful to show that beauty comes from within.’

- Alexander McQueen

VOSS (Spring/Summer 2001), also known as the ‘Asylum’ show, was staged inside a vast two-way mirrored box.The audience was reflected in the glass before the show began but, once it started, the trapped models could not see out.

©Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The collection featured a number of exoticised garments, including a coat and a dress appliquéd with roundels in the shape of chrysanthemums. A fragile, blood-red glass and ostrich feather gown offered a meditation on life's transience, while a thermal image of the designer's face was woven into the fabric of a silk coat.

The finale was inspired by a photograph by Joel-Peter Witkin entitled Sanitarium (1983), which depicted a voluptuous woman connected via a breathing tube to a stuffed monkey. On McQueen's catwalk, the role was played by the fetish writer Michelle Olley.

Typical of McQueen’s collections, VOSS offered a commentary on the politics of appearance, upending conventional ideals of beauty. For McQueen, the body was a site for contravention, where normalcy was questioned, and where the spectacle of marginality was embraced and celebrated.

'It's to do with the politics of the world - the way life is - and what beauty is.'

- Alexander McQueen

Romantic Naturalism

‘I have always loved the mechanics of nature and to a greater or lesser extent my work is always informed by that.’

- Alexander McQueen

Nature was the greatest, or at least the most enduring, influence upon Alexander McQueen. It was also one of the central themes of Romanticism. Many artists of the Romantic Movement presented nature itself as a work of art. McQueen both shared and promoted this view in his collections, which often included fashions that took their forms and raw materials from the natural world.

©Victoria and Albert Museum, London

'Things rot. I used flowers because they die. My mood was darkly romantic at the time.'

- Alexander McQueen

Plato's Atlantis

‘Plato’s Atlantis predicted a future in which the ice cap would melt, the waters would rise and life on earth would have to evolve in order to live beneath the sea once more or perish. Humanity would go back to the place from whence it came.’

- Alexander McQueen

Nature’s influence on McQueen’s work is most clearly reflected in Plato’s Atlantis (Spring/Summer 2010), the last fully realized collection the designer presented before his death in February 2010. Inspired by Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859), it presented a narrative that centred not on the evolution of humankind but on its devolution. McQueen created complex, digitally engineered prints inspired by sea creatures and introduced the towering ‘Armadillo’ boots. A film featuring model Raquel Zimmerman appearing to mutate into a semi-aquatic creature formed a graphic backdrop.

©Victoria and Albert Museum, London

For the Romantics, nature - starry skies, stormy seas, turbulent waterfalls, vertiginous mountains - was the primary vehicle for the Sublime. In Plato's Atlantis, this sublime experience of nature was paralleled with and supplanted by that of technology, and the extreme space-time compressions produced by the digital age. The collection was streamed live over the internet on Nick Knight's SHOWstudio in an attempt to make fashion into an interactive dialogue between creator and consumer. With its mixture of technology, craft and showmanship, Plato’s Atlantis offered a potent vision of the future of fashion. It was considered to be McQueen’s greatest achievement.

'There is no way back for me. I'm going to take you on journeys you've never dreamed were possible.'

- Alexander McQueen

The original version of Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York in 2011 was organised by the Costume Institute and became one of the museum's top 10 most visited exhibitions.

In partnership with Swarovski

Swarovski is delighted to partner the V&A in bringing Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty to London. The crystal house and Alexander McQueen share a rich history, beginning in the 1990s when Isabella Blow introduced the young maverick designer to Nadja Swarovski. Swarovski went on to support McQueen’s Spring/Summer 1999 collection, the first of numerous collaborations including the creation, alongside Tord Boontje, of the V&A’s Grand Entrance crystal Christmas tree in 2003; and the dramatic Swarovski Gemstone-encrusted Bird’s Nest Headdress for his Autumn/Winter 2006 collection. Swarovski has worked with designers since Daniel Swarovski’s precision-cut stones became prized ingredients in the dressmaking ateliers of Paris, beginning the tradition of close collaboration between Swarovski and haute couture that remains to this day.

Supported by

With thanks to Technology partner

Become a V&A Member

V&A Members enjoy a wealth of benefits, including free entry to exhibitions, previews, exciting events and the V&A Members’ Room. In addition, you will be supporting the vital work of the V&A.

Buy or Renew Membership Online