When it comes to food and drink, ceramics are usually reserved for tableware. However in the 17th century, Mexican búcaros – highly-polished earthenware pots made of fragrant red clay – served as both a container for water and food itself.

These water vessels were made from a distinctive red clay found in the region around Tonalá in the Mexican state of Jalisco. Celebrated for their fragrant clay body, which infused the water they contained with a delicate flavour and aroma, they were used to hold water at banquets, and were also thought to purify polluted water and detect poisoned liquids. Following the colonisation of Mexico by Spain throughout the 15th century, it became a practice of the Spanish upper classes to eat small fragments of the búcaros, which had been broken on the journey from Mexico to Spain. Some shards were eaten whole, while others were ground down into a finer powder and mixed with water. Contemporary accounts mention the taste of Tonalá clay, but also highlight its apparent medical benefits: eating the clay was believed to aid stomach and skin problems, symptoms of menstruation and even to act as a contraceptive.

Referred to as 'búcaros de Indias', (aromatic earthenware from Latin America), these vessels were exported to Europe in large quantities in the 17th and 18th centuries and became hugely popular. The fashion for búcaros is well recorded in literature and Spanish still-life paintings of the period. The Spanish playwright Lope de Vega wrote in 1608: "Girl of broken colour, either you have lovers, or you eat clay"(Niña de color quebrado / O tienes amores o comes barro) – de Vega is wondering if the young woman's pale skin is because she is lovesick, or is the result of eating too much clay. The painting Still life with bowl of chocolate, by Juan de Zurbarán (1620 – 49) shows the distinctive red clay vessel alongside luxurious imported blue and white porcelain cups, demonstrating the high status of the Mexican búcaros.

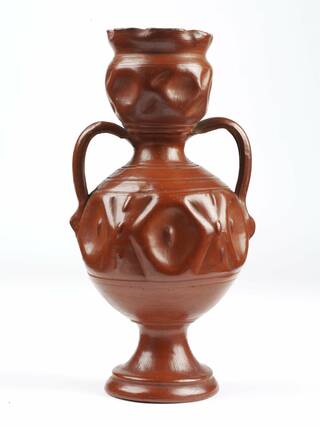

The búcaros were very cleverly designed to increase their function. The larger water storage vessels were typically dimpled which increased the jars' surface area. This aided evaporation through the thin walls of the unglazed clay, encouraging the water to cool, and release the clay's aroma. It also helped to cool and humidify the hot and dry air in the surrounding room. The dimpling was creatively designed in different ways on different vessels. The shapes were thrown on a wheel, and the decoration was done by hand, most likely using tools to indent the surface from the outside. Smaller beakers, such as the one in de Zurburán's painting, were often characterised with punched and stamped decorations.

The pots' glossy exterior was achieved by a process known as burnishing. A thin layer of watered-down clay, known as 'slip', would have been applied to the exterior. Then, using stones, the slip would be thoroughly polished, creating a high shine. Typically, ceramic vessels used for food and drink need to be glazed to be watertight and safe to use. However, glazing the clay would have created a barrier between the clay and the air, and its infusing power would have been lost. Burnishing provided a relative degree of watertightness, so that the fragrant properties of the clay could still be enjoyed.

In Tonalá today, there remains a culture of making ceramics in the tradition of the búcaros. Although they are no longer habitually eaten, they are still highly regarded for their beauty and eye-catching colour, and continue to be widely collected. We have 26 búcaros at the V&A, which were purchased in Madrid in 1872. Together they represent a unique appetite for clay as a material.

See all the búcaros ceramics in our collection.