During his career, William Morris produced over 50 wallpapers. These designs – many of which feature in the V&A's extensive Morris collection – adopted a naturalistic and very British take on pattern that was both new and quietly radical.

Remember that a pattern is either right or wrong. It cannot be forgiven for blundering, as a picture may be which has otherwise great qualities in it. It is with a pattern as with a fortress, it is no stronger than its weakest point.

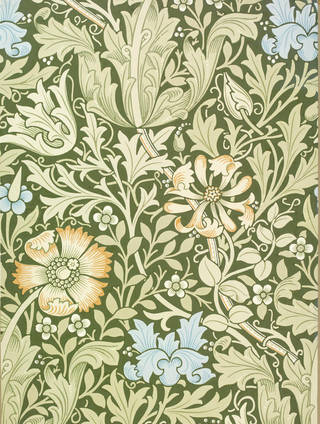

The success of Morris's wallpaper designs relies on his well-practiced and close observation of nature. Every one centres on plant-based forms, whether expressed in a luxuriantly naturalistic style (e.g. 'Acanthus' or 'Pimpernel') or one that is flatter and more formalised (e.g. 'Sunflower' or 'St James's Ceiling'). But Morris's designs were always subtle, stylised evocations of natural forms rather than literal transcriptions. He warned in his essay 'The Lesser Arts' (1877) against the likes of "sham-real boughs and flowers", and advised those designing wallpapers "to avoid falling into the trap of trying to make your paper look as if it were painted by hand". With a natural eye for pattern, Morris produced papers that not only balanced figuration and order, but which were (unusually for the time) distinctive.

Early designs

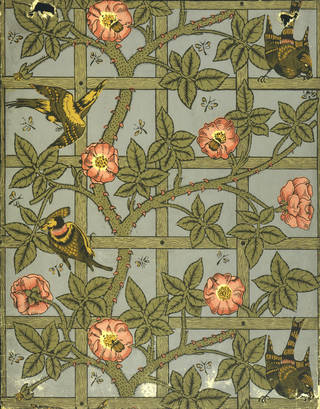

In the early 1860s the British wallpaper market was booming, with mass-produced papers offering homeowners a cheaper alternative to textile-based wall decoration. Conscious of wallpaper's accelerating popularity, Morris made it one of the first things his new interior decorations company put into serial production. The first paper Morris designed was 'Trellis' in 1862, a pattern suggested by the rose trellis in the garden of Red House, Morris's home in Kent; the second was 'Daisy' (1864), a simple design of naively drawn meadow flowers. The next pattern, 'Fruit', (1865), also demonstrated the same informal naturalism of Morris's first two designs. All these papers, and nearly all that Morris then went on to design were printed using hand-cut woodblocks loaded with natural, mineral-based dyes.

In the early years of 'the Firm' (as the directors of Morris's company, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. called it), sales of wallpapers were rather limited. Morris's designs didn't chime with fashionable taste, which in the 1860s generally favoured wallpapers in the super-naturalistic 'French' style. Enabled by sophisticated new printing techniques, this look was characterised by complex and unashamedly pretty designs that centred on exuberant flowers and the use of illusory effects such as trompe l'œil. Although Morris also focused on plants, his work was unprecedented because it celebrated the simple forms he saw in British gardens, fields and hedgerows rather than exotic, imported blooms.

Morris's quietly radical designs were also noticably different to those produced by the Design Reformers. Active since the Great Exhibition of 1851 (which had been full of elaborate 'French'-style wallpapers), this group of affiliated designers consciously rejected the popular vision of wall-based pattern. Full of moral purpose, they aimed to create papers that were less gaudy, more 'honest' and, without any illusion of three-dimensionality, more appropriate for use on a wall. Morris's work was also 'flat' and to a degree stylised, but it had none of the severe formality of the geometric wallpapers by designers such as Owen Jones and Augustus Pugin (famous for his work on the interiors of the Houses of Commons).

Out of step with both aspects of contemporary wallpaper design, Morris's work was considered 'peculiar' – the verdict of most London decorators when his papers first appeared. It was only when Charles Eastlake's book Hints on Household Taste (1868) stimulated a wider engagement in interior design that the trade (and to a lesser extent the public) began to take an interest in Morris's designs.

Becoming established

It was in the 1870s that Morris really mastered designing for wallpaper, a period during which he created many of his most enduring designs, such as 'Larkspur' (1872), 'Jasmine' (1872), 'Willow' (1874), 'Marigold' (1875), 'Wreath' and 'Chrysanthemum' (both 1876–87). These patterns all demonstrate exuberant scrolling foliage, a degree of three-dimensionality, and a closely interwoven foreground and background. They all required a complex printing technique that involved a large number of individual printing blocks, making the resulting papers more costly than those that carried Morris's earlier, simpler designs. Morris papers began to be recommended in many domestic advice manuals and design books, including the affordable Art at Home series (1876–83). As a result they gradually began to be found in the newly built homes of the 'artistic' middle classes.

The most consistent champions of Morris's papers were people operating outside of mainstream bourgeois society. Artists in particular appreciated his work. His designs were hung in the London home of Morris's life-long friend, the painter Edward Burne-Jones, and in 1875 were used in decorative schemes throughout 18 Stafford Terrace, a house in London bought by Punch cartoonist Edward Linley Sambourne. Morris's work was also endorsed by a number of families in aristocratic circles. In the first half of the 1880s the Earl and Countess of Carlisle, who were friends with Morris and his wife, used Morris's richly coloured 'Bird and Anemone' and two versions of a design centred on sunflowers to update the 18th-century interiors of Castle Howard in Yorkshire.

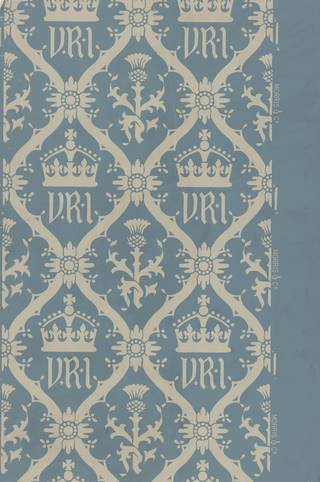

In 1880 Morris was asked to redecorate rooms at London's St. James's Palace, a job for which he created a special wallpaper: 'St. James's'. Carrying a suitably lavish pattern, this design required 68 separate printing blocks to create a repeat over two wallpaper widths, and had a vertical repeat of 127cm. Then in 1887 Queen Victoria commissioned Morris & Company to create a special wallpaper design for Balmoral Castle with the 'VRI' cipher incorporated into it. These commissions no doubt boosted the commercial success of Morris's papers, as well as helping secure his reputation: by 1884 'Morrisonian' had become a known term in the interiors trade – and wallpaper design was no longer an anonymous art.

Glaring problems

Despite the enthusiasm of artistic and aristocratic circles, Morris's papers were never universally admired as decorations for the ordinary home. Writing in the Journal of Decorative Arts in 1892, a commentator said that Morris's "…patterns are palatial in scale, and whilst their colouring is very beautiful and soft, the magnitude of the designs exclude them from ordinary work". Certainly many of Morris's later patterns – notably 'Acanthus' and 'St James's' – are on a grand scale. He felt that his larger patterns worked well in smaller rooms, but this went against the prevailing view of Victorian tastemakers, including Oscar Wilde, who apparently disliked Morris's work. Victorian architect Richard Norman Shaw also disapproved of Morris's delight in 'glaring wallpapers', saying that "A wallpaper should be a background pure and simple".

Despite his interest in its design, Morris still described wallpaper as a 'makeshift' decoration, treating it as only a tolerable substitute for more luxurious wall coverings. Some of the old snobbery about wallpaper as an imitative material, and a cheap option, still persisted and Morris, a wealthy man, preferred woven textile hangings for the walls of his own home. Between 1882 and Morris's death in 1896, Morris & Company issued a further 35 new wallpaper designs in a variety of types and prices. But from the early 1880s onwards wallpaper became less of a central concern for Morris as his energies were focused on the production of textiles at Merton Abbey Mills.

Although his papers were too expensive for most people to afford, towards the end of the 19th century Morris's designs began to have a significant influence on the wider market. Other designers and manufacturers began to produce cheaper papers in 'the Morris style', trying to recreate the appeal of his particular vision of organic growth controlled by a subtle geometry. And after Morris's death, the next generation of designers were conscious of working with his legacy. For example, Charles Voysey produced designs that show clear evidence of Morris's influence in his use of flat but complex patterns, as well as in his preference for stylised organic forms and motifs from nature.

Block-printing a William Morris wallpaper design

In a process that can take up to 4 weeks, using 30 different blocks and 15 separate colours, this video recreates the painstaking process in reproducing a William Morris wallpaper design from 1874.

Find out more about William Morris with our book.