Throughout his life, William Morris was fascinated by textiles and the techniques he needed to master to produce the effects he saw and admired in historical furnishings.

Satisfying his need for a manual as well as an intellectual engagement with design, textiles also offered Morris the scope to develop his talent for pattern across a huge number of different products. The V&A has extensive collections of his work in textiles – ranging from examples of his first experiments in embroidery in the early 1860s through to the imposing tapestry panels he helped to create only a few years before his death.

Embroidery

Embroidery was the first textile technique that Morris adapted for commercial use. Carried out before he was married, his first rather haphazard experiments in stitching fabric were an attempt to create a version of the medieval wall hangings he had admired since he was a boy. Although crude, these first goes were the foundation for a set of more refined embroidered wall hangings and curtains that Morris, his wife Jane and their friends later made for Red House, the Morris's first family home in Kent. One of these fabrics (stitched by Jane Morris) won Morris's new company an award in the 1862 International Exhibition, but their rather imposing historical style meant critics doubted how popular they would be in middle-class homes.

Despite its limitations, embroidery was the only practical means of decorating textiles in the early years of Morris's company. It was used to produce a small range of objects for domestic interiors (although the majority were made for friends or associates) and as part of commissions to decorate the interiors of a number of England's newly built churches. From the mid-1870s Morris and Edward Burne-Jones worked together (Morris providing decorative detail, Burne-Jones figuration) with teams of embroiderers on panels for a series of clients wealthy enough to clad the walls of their homes with hangings rather than wallpaper. They also designed and sold 'off the shelf' versions, as well as bespoke schemes for clients to complete at home.

Embroidery became a more significant part of the business following the opening of Morris & Company's new 'all under one roof' shop in Oxford Street in 1877. With Morris fast becoming a 'name' designer, people were keen to gain access to his work, and he was under increasing pressure to turn out staple commercial stock. He, and later his daughter May and assistant John Henry Dearle, produced a large number of designs for either completed panels or 'embroider yourself' kits that were used to make cushion covers, fire screens, portières (curtains hung over a door or doorway) and bedcovers. In 1885 Morris stepped away from direct involvement with embroidery, putting May (aged just 23) in charge of production.

Printed fabrics

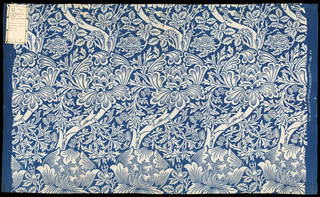

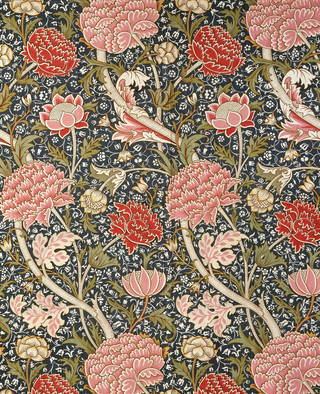

The first printed fabrics made by Morris's company, in 1868, were copies of 1830s white-ground chintzes, produced at Clarkson in Lancashire using blocks rather than the modern roller method (a revivalist rule that Morris would stick to throughout his career). These prints were effectively a test for Morris's first actual textile design, 'Jasmine Trellis' (1868–70), a pattern that was simplified to suit the palette of the mostly chemical dyes Clarkson used in its manufacturing process. Morris was happier with his second textile design, 'Tulip and Willow' (1873), although he was disappointed by the crude effect achieved with Prussian blue dye.

It was in the early 1870s, after many years collaborating with talented painters, and having had some success with his first wallpaper designs, that Morris accepted his gift was not for figurative form but for repeat patterns. He threw himself into the attempt to master the technical processes required to make his own products. In 1875, keen to re-establish the use of natural dyes, Morris began working with Thomas Wardle, the owner of a dyeing works in Leek, Staffordshire. The first textile likely to have been printed by Wardle is 'Marigold' (1875), a dense pattern that Morris also used for wallpaper. Morris produced a large number of textile designs over the next few years, all of which focused unapologetically on ordinary garden flowers: tulips, larkspur (delphinium), iris, bluebell, columbine, honeysuckle, roses and thistles.

Throughout the 1870s Morris had to rely on outside contractors to produce the quantities of material required commercially by his company, and the pressure increased when he opened his Oxford Street shop. His search for a site on which to consolidate his workshops and take full control of production ended in 1881 when he found Merton Abbey, an old textile-printing works near Wimbledon. Unprecedented in scale for a London manufacturer, the site offered a supply of soft water in the River Wandle, and the acres of ground necessary for the washing and drying of cloth. It also gave Morris the room to build the huge indigo vats that eventually helped him to create the 'right' blue dye that had previously eluded him.

In 1883 Morris used the complex indigo-discharge print method to produce a design that, although expensive, was still one of the company's most successful: 'Strawberry Thief'. This pattern was inspired by the fruit-stealing thrushes in the kitchen garden of his country home, Kelmscott Manor in Oxfordshire. The crisp outlines offered by indigo-discharge printing then allowed Morris to create a series of exuberantly complex designs. In 1884 he produced both 'Wandle' – the largest repeat attempted by Morris at 98.4 x 44.5cm – and 'Cray', his last significant design for a printed textile.

Woven fabrics

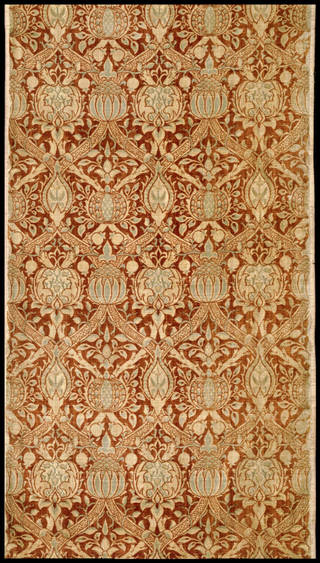

Of all the textile techniques that Morris taught himself, he left weaving until last. Mastering the working of the various looms needed for furnishings, tapestry and carpet weaving presented the greatest technical difficulties of his career. And Morris wanted to do more than weave traditional structures – he was also interested in producing experimental cloths created by mixing fibres in new ways. 'Tulip and Rose', the first dateable design by Morris for a woven furnishing textile, was registered in 1876 but he had been considering adding these to the firm's range for some time.

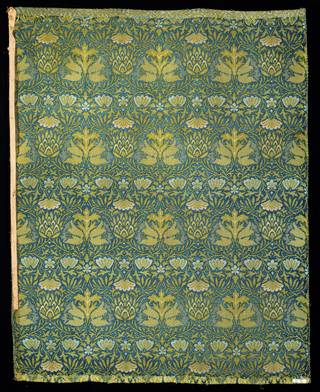

Morris produced designs for woven cloths for around a decade, and with significant commercial success. Silk, mohair and wool were all used and Morris achieved some impressive results – he even managed to embellish some patterns with gold threads. However, most of the weaves were flat jacquards in wool that were popular for curtains and wall-hung drapes – a medieval-style trend encouraged by Morris & Company. Morris studied many examples of early woven textiles in the collections of the South Kensington Museum (later to become the V&A). Many of his designs were inspired by 16th- and 17th-century Italian silks, and 'Peacock and Dragon', an imposing yet popular design from 1878, used striking, medieval-style figuration.

Initially, with no facilities to weave commercial quantities of cloth, Morris relied on outside contractors. The acquisition of Merton Abbey in 1881 enabled production to move in-house. Morris's interest in the technical aspects of weaving increased, and some of his final designs attempted to reproduce complex historical structures, such as the sumptuous brocaded Flemish velvets of the 15th and 16th centuries – in 'Granada', a design of 1884, for example. Morris's last identifiable designs for woven textiles were drawn in 1888; after this time, John Henry Dearle was responsible for this aspect of the company's output.

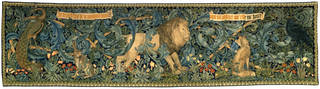

Tapestries

Morris taught himself what he called 'the noblest of all the weaving arts', first setting up a tapestry loom in 1877. His first completed piece was 'Acanthus and Vine' (1879), which apparently took 516 and a half hours to complete – time Morris had snatched (and meticulously recorded) from his commercial timetable by regularly getting up at dawn to work at a loom in his bedroom. The design of this piece was influenced by the 'large-leaf' verdure tapestries woven in France and Flanders in the 16th century, and its deliberately faded appearance was probably an attempt to recreate the wall hangings that had so impressed Morris when he had visited a hunting lodge in Epping Forest as a boy.

Tapestry weaving was established at Merton Abbey when company production was consolidated at the site in 1881, and Morris appointed John Henry Dearle to manage production. Large tapestry commissions were often designed by Morris, Dearle and other artists in collaboration, and executed by the company's experienced weavers on Flemish-style looms that Morris had built. Although by 1890 these tapestries were becoming increasingly popular with rich clients, they didn't offer a reliable source of income. The company made more money from the sale of smaller, affordable tapestry panels or cushions, which were available through the company's Oxford Street showroom and via overseas agents. Morris only designed one figurative tapestry 'The Orchard' in 1890, but Burne-Jones's work proved more popular with clients.

It was not until a commission in 1890 to decorate the interiors of Stanmore Hall in Middlesex, the last he worked on, that Morris was able to achieve his most important ambition, the production of a set of narrative tapestries in the medieval manner. Returning to the kind of Arthurian subject that Morris had so loved as a young man, he, Burne-Jones and Dearle used their wealthy client's large budget to create a set of lavish tapestries based on the theme of the Search for the Holy Grail.

Carpets and floor coverings

Morris began to design and outsource the machine production of carpet designs in the mid-1870s. It was probably the Kidderminster carpet (a coarse flat weave mainly made using woollen yarns) that he first attempted a design for, a style that was eventually produced by Morris & Company in around seven different patterns. Morris helped popularise this type of cheaper carpeting, which had tended to be used only for service corridors and secondary rooms. In the 1870s and 1880s Morris & Company received a number of orders from people keen to decorate large town and country houses in the new style, including Alexander Ionides, a London-based shipping owner who ordered 13 yards of Kidderminster carpet for his house in Holland Park.

Morris also designed carpets that were woven at Wilton, the town in Wiltshire with a long-established pedigree in carpet manufacture. Wilton-style machine-woven carpet – made from densely packed tufts of wool that are cut to create a velvety final texture – was eventually available from Morris & Company in 24 different designs, and over time proved its most popular flooring product.

In the late 1870s, inspired by his study of Persian rugs, Morris also moved into carpet production by hand. He revived the practice of hand-knotting and honed his skills by making small rugs at home. In 1879 he began to oversee the hand-knotting of what the company called 'Hammersmith' rugs in limited runs on looms installed in outbuildings at his London house. The looms were moved to Merton Abbey in 1881, where Morris & Company produced large Hammersmith rugs for a series of interiors commissions. These included one in 1889 for John Sanderson, a wool trader who lived in a house called Bullerswood in Chislehurst, Kent. The resulting 'Bullerswood' carpet was an exuberant amalgamation of almost every motif devised by Morris for carpets.

Find out more about William Morris with our book.