During her 60-year career, fashion designer Gabrielle Chanel (1883 – 1971) took a consistent and considered approach to her aesthetic.

Following the guiding principles of comfort, simplicity and wearability, Gabrielle Chanel continuously revisited and refined designs in a quest to hone and perfect her vision for the modern woman's wardrobe. As a result, certain pieces have become central to her distinctive style, and are now seen as iconic, internationally recognised signatures of the fashion house.

Jersey

Jersey made Gabrielle Chanel's name a force to be reckoned with in the world of French fashion. This inexpensive, utilitarian fabric was largely used for men's underwear, sportswear or stockings, before CHANEL transformed its status. Using knitted jersey to create her first garments, the fabric's fluidity and suppleness made it perfectly suited to the streamlined aesthetic and freedom of movement which Gabrielle Chanel sought to achieve. It quickly became a stylish and practical choice within the luxurious world of haute couture.

This 1916 belted blouse, made from fine-gauge silk jersey, is one of the earliest surviving CHANEL garments. Featuring a deep V-neck, wide sailor collar and turned-back cuffs, it was inspired by collared sailor's pullovers and would have been worn with a gathered skirt as part of a suit. The blouse is constructed in a flat T-shape, achieving a softly draped structure accompanied by a non-constricting silk tie belt. Comfortable, loose-fitting jersey jackets, blouses and skirts like this example proved instantly popular with Chanel's wealthy clients in the fashionable French seaside resorts of Deauville and Biarritz. They were ideal for informal seaside wardrobes and a far cry from the stiff tailoring and boned bodices and dresses of early 20th century women's fashion.

By November 1916, Gabrielle Chanel's penchant for jersey had become so well known that American and British Vogue declared 'Chanel is master of her art, and her art resides in jersey'.

As her style evolved, Gabrielle Chanel used permutations of knitted jersey throughout her career, continually updating and adapting it.

The little black dress

As early as the late 1910s, Gabrielle Chanel promoted the colour black as a stylish and versatile choice for women's wardrobes. Black had historically been associated with service, shop assistants and mourning dress, but for Chanel it was a chic symbol of modernity. The fashion house became inextricably linked with the colour black in October 1926 when American Vogue predicted a black CHANEL crêpe de chine day dress would be 'the frock that all the world will wear'. Dubbed the 'Ford' of fashion after the popular American car, CHANEL's 'little black dress', or LBD as it became known, was a global hit – as universal in its appeal as it was transformative. At a time when women were changing multiple times a day for different occasions, the LBD's versatility in being dressed up or down and seamlessly transitioning women from day to evening was a truly radical concept.

This little black dress is from CHANEL's Spring/Summer 1961 collection and illustrates her continued love of black for eveningwear through into the 1960s. Made of chiffon decorated with 12 gathered ruffles, it features a striking black taffeta bow on the back. It is one of several CHANEL designs worn by lead actress Delphine Seyrig in the 1961 New Wave film Last Year at Marienbad.

Black remained central to Gabrielle Chanel's work throughout her career, with designs often bring stripped of decoration to foreground the silhouette and style of the dress. She also played with black-on-black embellishment in sparkling sequins and jet beads, and also experimented in black silk crepe, silk chiffon, satin, silk velvet and georgette.

Black lace was a particular favourite of Gabrielle Chanel's. Cocktail and evening dresses such as this 1956 example were a staple of her collections during the 1950s and 60s. Its strapless, form-fitting silhouette is made of black lace over silk, constructed over a boned foundation. The trumpet-shaped skirt flares to a triple flounce at the hem that is supported by a layered petticoat which has been heavily stiffened with a deep band of black net.

The little black dress remains an essential part of contemporary women's wardrobes, and while Gabrielle Chanel was not the only designer to promote black in fashion, her continued love affair with the colour throughout her career cemented the LBD's acceptance and position in fashion history.

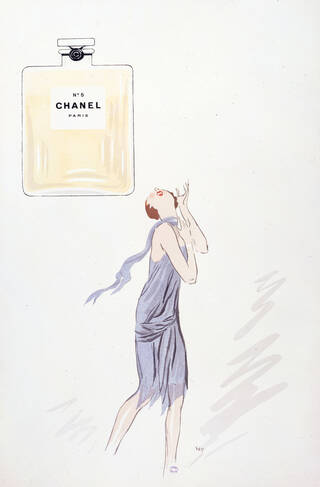

CHANEL N°5

Since its inception in 1921, CHANEL N°5 has been the cornerstone of the CHANEL empire. Designed as an extension of her clothing and echoing her vision of modernity, Gabrielle Chanel made her debut perfume the signature scent of the fashion house.

Created by the Russian-born French perfumer Ernest Beaux, who had previously supplied the Russian imperial court, N°5 was a unique scent made from over 80 ingredients including jasmine, ylang-ylang, sandalwood, May rose and neroli. Beaux initially created ten samples and Gabrielle Chanel chose number five: her favourite number and the ultimate name for the scent.

N°5 was notable for its experimental use of aldehydes, an organic chemical compound, which Beaux used in such high volumes that they blended all the individual ingredients to create an abstract and, at the time, incredibly modern perfume. The resulting scent had no discernible floral fragrance which was markedly different to most 1920s women's perfume.

In contrast to the highly decorative, Art Nouveau-inspired bottles of other perfumers, Gabrielle Chanel chose a simple square bottle reminiscent of medicine vials or men's perfume bottles. The original 1921 bottle featured a square stopper etched with two interlocking C's enclosed in a circle – the first time CHANEL used what would become iconic shorthand for the brand. In 1924, the square stopper became facetted and octagonal, and the bottle became bevelled. Despite minor modifications, the stark and clean design with simple off-white label and black lettering has remained largely unchanged since it was launched. Likewise, the formula for CHANEL N°5 has stayed the same since Ernest Beaux first created it over a century ago.

N°5 would go on to become the world's bestselling fragrance and remains a bestseller today, underlining its modern and timeless appeal. The Queen wore N°5, as did Marilyn Monroe, who drew on the global fame of the perfume to tease her fans in a 1952 interview, stating that she only wore N°5 to bed. The perfume's unceasing popularity has ensured the ongoing commercial success of the House of CHANEL overall.

The tweed suit

The CHANEL tweed suit was undeniably one of Gabrielle Chanel's most enduring and iconic designs, and became the defining garment of her post-war legacy. Tweed suits first featured in her collections in the 1920s when she transformed their status from traditional sports and outdoor wear to fashionable daywear – but it was following her 1954 return to fashion that the CHANEL suit became so synonymous with the CHANEL look.

As with all CHANEL designs, the suit followed her design manifesto that clothes should be elegant yet easy to move in, ultimately balancing comfort, simplicity and style. Her preference for supple fabrics and a cardigan-like cut for jackets ensured much greater freedom of movement for the wearer and saw the CHANEL suit become the preferred sartorial choice for many of the world's most celebrated women in the 1950s and 60s.

High profile clients including Princess Grace of Monaco, Elizabeth Taylor, Jacqueline Kennedy and Marlene Dietrich all frequently purchased their couture suits from CHANEL. Their extensive press coverage wearing CHANEL ensured that the CHANEL suit was ubiquitous in Western fashion press in both the editorial and society pages by the 1960s.

.jpg)

Hollywood actress Lauren Bacall ordered this rose-pink tweed suit from CHANEL's Spring/Summer 1959 collection. It features many of the quintessential signatures of a classic CHANEL suit: a straight-cut jacket, matching jacket lining and blouse fabric, gilded lions' head motif buttons and a gilded metal chain sewn into the jacket hem to ensure the fabric falls perfectly. The film star was photographed wearing the suit in July 1959 at London Airport (now Heathrow), about to board a plane to Biarritz with her two children for their family holiday. Bacall paired the suit with a flower in her top buttonhole and a pair of white gloves. CHANEL's tweed suits appear to be a favourite of Bacall's when travelling during this period – she was photographed at the same airport just two months earlier, wearing a similar checked tweed CHANEL suit.

.jpg)

Gabrielle Chanel's continual refinement of her formula, offering fresh colours, fabrics and trimmings in line with the fashion zeitgeist, has ensured the CHANEL suit's undying popularity, cementing its place in fashion history as a timeless classic.

The 2.55 handbag

Accessories were fundamental to Gabrielle Chanel's concept of a harmonious silhouette. They reflected her pragmatic vision of fashion and provided recognisable codes which underlined the unity of her style.

Following its launch in February 1955, the 2.55 handbag (named after the month and year it was created) swiftly became a highly desirable CHANEL classic. It came in three different sizes, in either lambskin, jersey or silk satin. The design included a front fastening cover flap with rectangular turn lock and featured two sets of eyelets which made the metal strap adjustable, allowing it to be carried by hand or over the shoulder. The handbag's distinctive diamond quilting (inspired by equestrian wear) and gilt metal chain-link strap (sometimes intertwined with leather), have become instantly recognisable hallmarks of CHANEL's signature style. Its numerous pockets, special lipstick compartment, wide opening and red lining – allowing you to easily see the contents at a glance – ensured the 2.55 was a stylish yet practical accessory for the modern woman.

To mark the 50th anniversary of the 2.55, CHANEL's then creative director Karl Lagerfeld (1933 – 2019) rereleased the original design. While there have been several variations on the original – including the interlinking C-clasp lock in the 1970s – the CHANEL brand continued referencing the 2.55 in collections spanning seven decades since its inception. As such a classic design, the 2.55 remains a highly sought after and collectable icon of fashion today.

Two-tone shoe

In 1962 Gabrielle Chanel chose Massaro, a shoemaker based on the prestigious rue de la Paix in Paris, to develop the ultimate CHANEL shoe. Established in 1894, the Massaro house was a discreet address known by word of mouth and personal recommendation. As always, Gabrielle Chanel designed to suit her own wardrobe, selecting a beige leather to match her skin tone, giving the appearance of an elongated leg. A small black toecap gave a tiny punctuation over the toes that visually shortened the foot, and protected the paler leather from scuffs. The elasticated strap and low heel ensured comfort and ease of movement.

As was the custom, many haute couture clients regularly ordered individual pairs of shoes from their own shoemakers to match each outfit. Gabrielle Chanel advocated for a streamlined approach, wearing her beige and black two-tone slingbacks with everything.

The design proved so popular that Gabrielle Chanel went on to introduce further toecap options: in brown, navy and gold for eveningwear. Multiple versions of the slingback have become a staple of contemporary CHANEL collections, alongside two-tone ballerina slippers, pumps, mary janes and boots.

The original slingback design in beige and black remains a highly coveted CHANEL classic and a perennial source of inspiration for the House of CHANEL.

Costume jewellery

Costume jewellery made from inexpensive materials or imitation gems was fundamental to Gabrielle Chanel's design aesthetic. Over the years she amassed a large collection of fine pieces, much of it gifted to her. For her clients she promoted costume jewellery to be worn in abundance with her paired back garments.

.jpg)

Imitation pearls became a particular CHANEL hallmark that she used in necklaces, brooches or as buttons on suits. In 1931, she was hailed as being 'largely responsible for the vogue for artificial pearls'. Her championing of costume jewellery was a radical challenge to accepted notions of good and bad taste, and did much to elevate the status of costume jewellery within fashion.

Gabrielle Chanel's boutiques offered a dazzling range of costume jewellery to wear with her garments from the early 1920s onwards. Key motifs such as flowers, wheatsheaves, stars and the sun regularly appeared in her jewellery collections and became synonymous with the brand's style. The lion's head, a nod to her zodiac sign Leo, was embossed on medallions, brooches and collars.

Gabrielle Chanel worked with some of the best designers and jewellery-makers in Europe to produce her jewellery collections, including Count Étienne de Beaumont from the 1920s, Maison Gripoix from the 1930s, Fulco di Verdura from 1933 and François Hugo in the late 1930s.

Many of the pieces in the V&A collection are Gabrielle Chanel's post-war designs created by goldsmith and jewellery-maker Robert Goossens. Together they found inspiration in the bejewelled antiques of Venice, Byzantium, Persia and the Celtic world that they saw in museums and books. Occasionally Gabrielle Chanel asked Goossens to copy an ancient pendant, although more often the historical artefacts served as muses from which to create something new.

Find out more about the exhibition, Gabrielle Chanel. Fashion Manifesto.

See CHANEL objects in Explore the Collections.