The earliest automobiles emerged in the 1880s from a soup of other technologies. In construction and form they were strongly influenced by both the carriage and the bicycle, borrowing and modifying designs for wheels, tyres, suspension systems and bodies.

Through the late 19th century there was a huge amount of speculation about the form that the car would eventually take, much of this centred on the issue of motive power. By the 1880s three dominant types of motor had been developed – steam, gasoline and electric – and the relative benefits of each were discussed at length by makers, lobbyists and the press.

On both sides of the Atlantic there was a strongly held belief in the potential of electricity as the fuel of the future. Although electric batteries did not yet have the range of the petrol engine, many believed that the technology would soon catch up, and that its other advantages far outweighed this (temporary) blip. An article In Scientific American stated in 1899:

"The storage electric motor is clean, silent, free from vibrations, thoroughly reliable, easy of control, and produces no dirt or odor ... The greatest demand for an efficient automobile comes, not from people who wish to take long tours through the country, or whose business calls them to any considerable distance from an electric charging station, but from surgeons, expressmen, and those private citizens who wish to keep a carriage".

Campaigns to make the electric car the vehicle of everyday use often directly targeted women by ascribing the electric engine with supposedly 'feminine' characteristics: quiet, smooth, domestic and easy to control. As one advertisement stated: "any woman can charge her own electric with a GE Rectifier ... there are no tiresome trips to a public garage, no waiting – the car is always at home, ready when you are".

In contrast to this picture of the middle-class woman recharging her car for a quiet drive through city suburbs, the image that developed around the early gasoline motorist was largely one of speed, recklessness and long distance. The petrol car, more likely to break down, noisier and able to travel further distances without the need for a charging point, quickly became associated with adventure and risk.

It was in part this association between gasoline and adventure that led to the eventual elimination of steam and electric cars in favour of the petrol engine. By as early as 1900 petrol cars had already started to pull ahead, with drivers embracing an ideal of the fast engine that could travel off-road under the hand of a skilled, sporting driver.

In the early 20th century, in step with the growing dominance of the petrol car, gasoline became an increasingly valuable resource. During the First World War, and throughout the 1920s, there were concerted efforts by European countries and the USA to gain control of world oil supplies. Oil had become a significant player in global power, with increasingly elaborate systems developed to control its movement across national borders and through global trading networks.

The market for petroleum reached its peak after the Second World War. Driven directly by a massive increase in car ownership, demand for gasoline shot up. Production was able to keep step with rising consumption due to increasingly sophisticated techniques for drilling, transportation, refining and prospecting that had been developing steadily since the 1920s. By 1964 oil had surpassed coal as the world's most commonly used fuel, and by 1970 rich countries were consuming four times as much oil as they had in 1950.

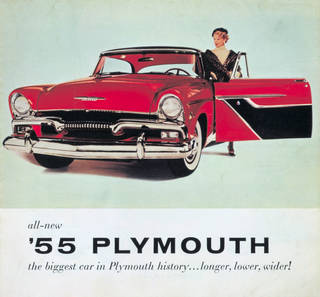

Major oil companies were keen to sell petroleum as the key to a new way of living. This began with the automobile, with cheap fuel enabling US car manufacturers to produce ever larger and more petrol-hungry models. Giant, gas-guzzling engines became the norm, heralding a huge shift in fuel efficiency: while a large Cadillac would have driven around 20 miles to the gallon in 1949, by 1973 American-made cars averaged only 13.5 miles per gallon.

Following the formation of OPEC (the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) in 1970, oil-producing member states agreed not to tolerate further lowering of crude-oil prices by major multinationals. World oil prices quadrupled between 1973 and 1975, sending shock waves through North American and European markets.

At the same time that the global geography of oil was shifting, there was also increasing alarm about the vast environmental destruction caused by the gasoline engine. This ranged from disastrous spills out of a growing network of oil rigs, tankers and pipelines, to the increasingly urgent problem of carbon emissions and air pollution. Although manufacturers had been aware of the huge rate of automobile emissions since at least the 1950s (and even 1890s' accounts of petrol motors often discussed their 'dirtiness'), there was no action to limit this until a wider public engagement with the issue in the late 1960s and 70s. With 60 – 80 per cent of US air pollution deriving from motor vehicles in the mid-1960s, a number of state and eventually federal measures were introduced to force car manufacturers to reduce emissions. Even after the Clean Air Act was passed in 1970, it took most of the rest of the decade for many US manufacturers to make any real changes to the levels of pollution from their cars.

In response to a growing awareness of air pollution, Ford, General Motors and other companies such as General Electric made highly publicised attempts to design battery-powered cars in the mid- to late 1960s. More significant than these short-lived electric experiments was a consumer-led shift away from large cars. Where giant gas-guzzlers had previously reigned supreme on the US market, drivers hit by increases in fuel prices began to buy smaller cars in the early 1970s. This triggered a growth in the sales of fuel-efficient Japanese and European models, prompting American manufacturers to scale down, in an attempt to match the competition.

Unfortunately these changes were very temporary. With the collapse of high oil prices in the mid-1980s, and an economic boom in the 1990s, drivers were quick to return to larger, petrol-hungry models. Huge gas-consumers like SUVs (sport utility vehicles) gained a massive proportion of the global market and, according to the UN, energy use for transport (of which 95 per cent was petroleum) increased by 66 per cent between 1973 and 1996.

As we move into the third decade of the 21st century we inhabit a world in crisis. In October 2018 the UN released a climate report warning of the now-unavoidable and disastrous consequences of global warming. Without extremely drastic measures in the next 10 years, the planet is facing huge rises in sea levels, a devastating loss of biodiversity through species extinction, spreading areas of drought and large-scale loss of forest. While the combustion engine is not the only factor that has fuelled this fire, petrol cars remain a significant contributor to carbon gas emissions.

Triggered by this dire environmental situation, electric vehicles are beginning to increase in number and profile. Their new fashionability was perhaps best illustrated by the wedding of Meghan Markle and Prince Harry in spring 2018, when millions of viewers watched as the happy couple drove away from their reception in an e-Type Jaguar fitted with an electric engine. Despite the seeming optimism of the gesture, the e-Type's neat splice between forward-thinking and nostalgia does point to murky waters ahead. Jaguar's decision to encase their electric future in the body of a speeding 1960s' sports car highlights the difficulties inherent in moving on from the dream of gasoline.

Although electric cars are beginning to be produced in larger quantities, with manufacturers paying greater attention to the need for an alternate fuel, petrol cars remain hugely dominant and the non-petrol engine is still (as it was in the 1890s) very often discounted due to concerns about battery range and the lack of a refuelling infrastructure.

It seems that the same culture that shaped 19th-century attitudes to electric and petrol cars continues to have an influence. The long life of the so-called Jeep 'Cherokee' (now approaching its 45th year of production) highlights the extent to which manufacturers persist in selling drivers the myth of the wilderness, and a vision of heading out to conquer the unknown.

This is an edited extract from 'The Race to Extraction' by Lizzie Bisley, taken from the exhibition book Cars: Accelerating the Modern World