"Of course, that a scientific study of aerodynamics […] would be translated to a world of static objects that were hardly in need of going anywhere fast is one of the great comedies of 20th-century design".

On 29 April 1899 a young Belgian entrepreneur did something that had never been done before. On a public road outside Achères – a town on the outskirts of Paris – Camille Jenatzy propelled his body 105.882 kilometres per hour. He did so using just a metal tube, a chassis with four rubber wheels and an electric engine. By exceeding the 100 km/h mark for the first time, Jenatzy had broken the world land-speed record. The vehicle that won him the honour was called La Jamais Contente, which translates as 'the never satisfied'. Although it was jokingly a reference to his wife, the name also speaks of Jenatzy's stubborn drive to improve on his own speed records (he had already set two in the previous four months). But 'never satisfied' was also prophetic, as it would go on to perfectly symbolise the compulsion to go ever faster, which has afflicted the hearts and minds of thousands of engineers, designers, mechanics and drivers over the past 120 years.

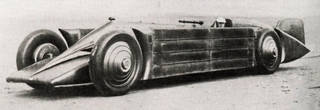

By the 1920s and '30s, the public appetite for speed was not only helping to transform new driving technologies but was also helping to fundamentally change the look of everyday objects. Most improvements to car performance were taking place under the bonnet, invisible to the naked eye, but in the first few decades of the 20th century the application of aerodynamic testing began to have a drastic impact on the exterior shape of a car. From La Jamais Contente's torpedo body to the Golden Arrow's (1928) low-slung, angular form, these early streamlining tests were mostly focused on one-off experimental cars designed purely to break records and, as such, for many years the aesthetic of streamlining remained relatively marginal. It was Hungarian-born engineer Paul Jaray, however, who sought throughout the 1920s and '30s to bring the look to a popular audience by applying the principles of streamlined car design to modern production cars.

Working at Luftschiffbau Zeppelin in 1915, Jaray was able to use the company's wind tunnel to make his first major attempt at stream-lined design: the airship Lz-120 Bodensee, whose bulbous front and tapered end would influence all subsequent zeppelin designs. In the 1920s he used this knowledge to try and develop a comprehensive set of principles for streamlined car design, setting up a business to license these designs to automobile manufacturers. But while Jaray had discussions with many major car companies, the Czech company Tatra was the only one finally to mass-manufacture a streamlined car in collaboration with him. After working with Tatra chief designer Hans Ledwinka, the t77 was revealed in 1934; it was sleek, low and incorporated a fin running down its back.

Other streamlined designs would follow: the Chrysler Airflow debuted in the same year, with some dubious similarity to many of the ideas Jaray had been trying to sell to the company over the previous few years. Peugeot was also a major adopter of streamlining methods, most noticeable in its 402, which was launched in 1935, and its 202, a supermini that launched in 1938, with its characteristic sloping front grille. Perhaps most conspicuous, though, was the influence of the t77's streamlined successor, the t97, on Adolf Hitler and Ferdinand Porsche. Hitler specifically named Tatra as an example to follow, while directing Porsche to design him a people's car, and the resulting Kdf-Wagen – the Beetle – bears many resembling traits.

Meanwhile, the enthusiasm for streamlining, and the characteristic teardrop shape that could be found in many of Jaray's early aerodynamic tests, were already taking hold in the world of product design. Of course, that a scientific study of aerodynamics – applied to zeppelins and automobiles for reasons of speed, efficiency and handling – would be translated to a world of static objects that were hardly in need of going anywhere fast is one of the great comedies of 20th-century design. Soon, anything and everything that could be styled with sleek curves and tapered ends, to signify modernity and futurity, was given such a treatment. Pencil sharpeners, fans, hats, chairs, irons and even meat slicers were formed as if they had been put through wind-tunnel testing, reducing what was a serious scientific study to a cheap marketing ploy.

The industrial designer Raymond Loewy treated streamlined style as some kind of natural evolutionary step. His 1930 Chart of the Evolution of Design depicts the morphing silhouettes of a car, a train, a telephone, a clock, a chair, a stemmed glass, a dress and a bathing suit. With each object he argued that over the course of time their essential shapes had improved and evolved, towards the smooth, flowing minimal forms characteristic of his era.

Streamlining eventually fell out of fashion, but the tendency to translate technical advancements in speed into other forms and mediums still remained. An equally misguided episode took place immediately after the Second World War, when Harley Earl, head of General Motors' Styling Department, became deeply inspired by the image of fighter jets and started translating their look into the design of his cars. He began with a series of concept cars – Firebird I-IV – that were powered by jet engines and were kitted out with all the latest in aviation control technology. He soon found ways to incorporate a sense of cutting-edge flight into his production cars by including tail fins (mainly used for stabilisation at high speeds) and 'dagmar' bumpers (to convey artillery shells or projectile missiles) on his Cadillacs, along with an excessive use of chrome. None of this had anything to do with the actual speed or functionality of the car, and as these accessories grew with each subsequent model, it became clear that styling had entered an aesthetic dead end, in need of a rethink.

This article is an edited extract from the exhibition catalogue Cars: Accelerating The Modern World, by Brendan Cormier & Elizabeth Bisley