Albumen print

The albumen print was invented in 1850 and was the most common type of print for the next 40 years. It produced a clearer image than its predecessor, the salted paper print. An albumen print was made by coating paper with a layer of egg white and salt to create a smooth surface. The paper was then coated with a layer of silver nitrate. The salt and silver nitrate combined to form light sensitive silver salts. This double coated paper could then be placed in contact with a negative and exposed to the sun to produce a print.

Autochrome

Autochromes were the first really practicable colour photographs and were made by a process patented in 1904. An autochrome was a coloured, transparent image on glass, similar to a slide. The colour came from a layer of translucent granules of potato starch, each dyed red, blue or green to create a coloured mosaic on the glass plate. During exposure, light travelled through these granules to reach a light sensitive layer below; red granules would only allow red light to travel through, and so on. The light sensitive layer was therefore selectively exposed by colour. When the autochrome was held up to the light, the coloured granules were viewed in combination with the black and white image behind to create a colour photograph.

C-type print

A c-type print, usually made from a colour negative, is a colour print in which the print material has at least three emulsion layers of light sensitive silver salts. Each layer is sensitised to a different primary colour - either red, blue or green - and so records different information about the colour make-up of the image. During printing, chemicals are added that form dyes of the appropriate colour in the emulsion layers. It is the most common type of colour photograph.

Calotype

William Henry Fox Talbot patented the Calotype process in 1841. It is the direct ancestor of modern photography because it used a negative permitting multiple positive prints to be made from the negative and development of the latent image. The negative was a sheet of high quality writing paper which had been made light-sensitive with chemicals. Because the image was contained in the fabric of the paper rather than on a surface coating, the paper fibres tended to show through in the prints making them mottled and relatively ‘sketchy’.

Carbon print

Carbon printing was introduced from 1864. A sheet of paper was coated with a layer of light-sensitive gelatin which contained a permanent pigment (often carbon). It was then exposed to daylight under a negative. Carbon prints have a matt finish and can be produced in a variety of colours, ranging from rich sepia tones to cooler shades of grey and blue. Because of their resistance to fading they were much used in the 1870s and 1880s for book illustration and commercial editions of photographs.

Chemigram

Chemigrams are made by directly manipulating the surface of photographic paper, often with varnishes or oils and photographic chemicals. They are produced in full light and rely on the maker’s skill in harnessing chance for creative effect. Documented experiments are often an important part of the process.

Collage and Montage

Collage (from the French 'coller' - to stick) involves combining fragments of different materials, which are not necessarily photographic. There is normally no attempt to conceal the edges of the pieces and the artist might add pencil, pen or brush work onto the surface. Montage (from the French 'monter' - to mount) involves combining diverse photographic images to produce a new work. This is often achieved by rephotographing the mounted elements or by multiple exposures.

Cliché-verre

Cliché-verre is a photograph made from a hand-drawn negative. The design is either drawn or painted on to a sheet of glass, or, alternatively, scratched on to a piece of glass that has been made opaque by being painted over or blackened with smoke. The sheet of glass is then placed on a sheet of sensitized paper and exposed to light. The blackened area of the glass acts as a stencil, creating an image on the paper below only where light was able to pass through the glass.

Collodion negative

A sheet of glass hand-coated with a thin film of collodion (guncotton dissolved in ether). This contains potassium iodide and is sensitised on location with silver nitrate. For maximum sensitivity, the plate had to be exposed while still wet and developed immediately. Introduced in 1851 by F. Scott Archer, the process gave a high resolution of detail. Dry collodion negatives, introduced later, were made by covering the collodion with a layer of albumen or gelatin.

Discover more about the wet collodion process.

Collotype

The collotype process was used between about 1870 and 1920. A glass plate was coated with sensitised gelatin and exposed under a negative. Light passed through the negative would harden the gelatin on the glass plate. The unexposed gelatin would absorb the water when washed and the exposed gelatin would repel it. The washed glass plate would be coated with ink, adhering to the exposed gelatin and printed onto fine paper.

Cyanotype

The cyanotype process for making prints was invented by Sir John Herschel in 1842 and came from his discovery of the light sensitivity of iron salts. A sheet of paper was brushed with iron salt solutions and dried in the dark. The object to be reproduced - a plant specimen, a drawing or a negative - was then placed on the sheet in direct sunlight. After about 15 minutes a white impression of the subject formed on a blue background. The paper was then washed in water where oxidation produced the brilliant blue - or cyan - that gave the process its name.

Daguerreotype

The invention of the daguerreotype process was announced by the Frenchman Louis Daguerre in 1839 and was widely acclaimed. The image produced had a startling clarity and made the daguerreotype hugely popular as a medium for portraiture until the middle of the 1850’s. To create a daguerreotype, a silver plated sheet was given a light sensitive surface coating of iodine vapour. After a long exposure in the camera, the image was developed over heated mercury and fixed in a solution of common salt. As the image lies on the surface of a highly polished plate, it is best seen from an angle to minimise reflections.

Discover more about the daguerreotype process.

Digital image

Digital images are created using a gridded mosaic of light sensitive picture elements, called pixels, embedded on a computer chip. The pixels emit electrical signals in proportion to the amount of light they receive and these signals are converted to numbers and then stored electromagnetically - in a computer or on a disc, for example. Digital images can be manipulated and altered by computer and regenerated in many ways: on computer or television screens, on film, printed or projected. The technology for producing digital images is evolving rapidly with new possibilities constantly emerging.

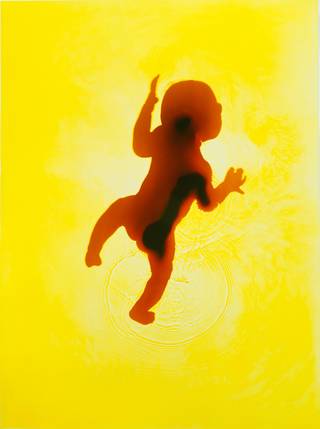

Dye destruction print

Dye destruction prints are made using print material which has at least three emulsion layers, each one sensitised to a different primary colour - red, blue or green - and each one containing a dye related to that colour. During exposure to a colour transparency, each layer records different information about the colour make-up of the image. During printing, the dyes are destroyed or preserved to form a full colour image in which the three emulsion layers are perceived as one. Dye destruction prints are characterised by vibrant colour. The process used to be called Cibachrome: it is now known as Ilfochrome.

Dye transfer print

Dye transfer prints are prized for their rich colours and relative permanence. A dye transfer print is produced from three separate negatives made by photographing the original negative through red, green and blue filters. A mould is made from each of the three negatives which are transfered to a gelatin coated paper to produce a full colour image.

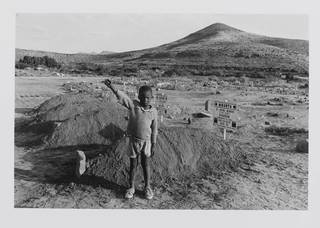

Gelatin-silver print

Gelatin silver prints are the most usual means of making black and white prints from negatives. They are papers coated with a layer of gelatin which contains light sensitive silver salts. They were developed in the 1870's and by 1895 had generally replaced albumen prints because they were more stable, did not turn yellow and were simpler to produce. Gelatin silver prints remain the standard black and white print type.

Watch photographer, Sunil Gupta, as he demonstrates how to make a gelatin silver print using a negative from his first photographic body of work, Christopher Street, in 1976.

Gum bichromate

This type of printing, popular in the early twentieth century, allowed a high degree of control and artistic manipulation. The paper is brushed with a coating of gum arabic, water, pigment and potassium (or ammonium) bichromate, and usually exposed in contact with a negative. Brushing or washing the surface could dissolve areas of the coating hardened more or less by exposure, thus changing contrast and adding effects reminiscent of drawing or painting

Heliograph

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce invented this process in which he first coated a pewter plate with light-sensitive Bitumen of Judea (asphaltum). Taking an existing engraving on paper, he waxed it to make it translucent and placed it on the plate in the sun. Its rays hardened the bitumen under the light areas of the image. The plate was washed with a solvent, which removed the unexposed areas, and etched in acid. It was then ready for inking and printing. Recent technical analysis of the Niépce plates in the Victoria and Albert Museum has revealed the use of another light-solidified material, which resembles the resin obtained when heating lavender oil, and a range of levels of etching and hand-tooling over the plates. Niépce also experimented with the plates inside a camera, producing the earliest known surviving photograph made in a camera, View from the Window at Le Gras (1826 or 1827).

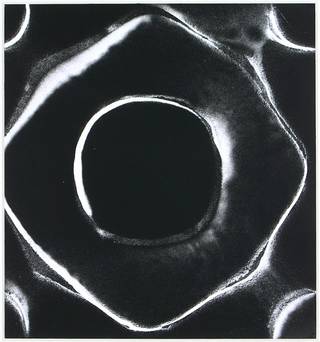

Luminogram

A variation of the photogram. In a luminogram, light falling directly on the paper forms the image. Objects placed between the light and the paper (but not touching the paper) will filter or block the light, depending on whether they are transparent or opaque.

Photocopy

Commercial photocopying was introduced by the Xerox company in 1959. Most current photocopiers rely on xerography technology, a dry process using electrostatic charges on a light-sensitive photoreceptor to first attract and then transfer toner powder onto paper in the form of an image. Heat, pressure or a combination of both is then used to fuse the toner onto the paper.

Photogenic drawing

Photogenic drawing was William Henry Fox Talbot’s name for the results of his first cameraless photographic process which he announced in 1839. In its simplest form a smooth high quality sheet of writing paper was immersed in a solution of table salt and then dried. Talbot brushed the paper with a solution of silver nitrate. This combined with the salt to produce silver chloride which is light sensitive. Small objects such as leaves and lace could then be placed on the paper and exposed to sunlight. This produced a light image of the object against a dark background; in other words, a negative image.

Photogram

A photogram is a photograph made without a camera or a lens by placing an object or objects on top of a piece of paper or film coated with light-sensitive materials and then exposing the paper or film to light. Where the object covers the paper, the paper remains unexposed and light in tone: where it does not cover, the paper darkens. If the object is translucent, midtones appear. After exposure the paper is developed and fixed.

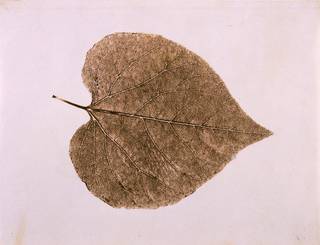

Photographic and photoglyphic engraving

These are methods of photographically producing copper or steel printing plates that can then be used in a conventional press. The first was patented by William Henry Fox Talbot in 1852, and the second by him in 1858. At first, a copper or steel plate was coated with a gelatin solution made light-sensitive with potassium bichromate. The object to be depicted, such as a leaf or piece of fabric, was placed on top. Exposure to daylight hardened the areas not covered by the object. The unhardened areas were then washed off and the plate etched in acid. With etching complete, the gelatin was removed and the plate could then be printed. The addition of screens or other graining allowed Talbot to devise his second process, which had a much wider tonal range. A glass photographic positive was put over the sensitized plate and used to make the image. Nature made the faithful original photographic drawing, but, in the final prints, carbon-based ink relied on nothing light-sensitive and preserved the original image for posterity. This was the direct forerunner of the photogravure process.

Photogravure

Photogravure is a process for reproducing a photograph in large editions. It uses gelatin to transfer the image from a black and white negative to a copper printing plate. The gelatin carries the image because it hardens in proportion to its exposure to light. Areas of the gelatin not exposed stay soft and can be dissolved away in water. What remains is a gelatin version of the image which is then pressed onto a copper plate. The plate is placed in an acid bath. Where the gelatin is thick, the acid eats the metal away slowly, where the gelatin is thin or absent, the acid eats faster. Consequently, the plate is etched to different depths according to the tones of the original image. When inked for printing, the varying depths hold different amounts of ink.

Pigment print

This form of digital print is made via an inkjet printer. As a form of art reproduction, inkjet prints became more widely available in the 1980s, when digital printer technology improved and printers became less expensive. The first inkjet prints were created with Iris printers, developed by Iris Graphics, Inc., and are therefore sometimes known as Iris prints. High-quality versions are sometimes termed giclée prints. Some types of digital inkjet printing use pigments rather than ink or dyes. Pigment particles embed into the receiving paper and are therefore more permanent.

Platinum print

The process for making platinum prints was invented in 1873 by William Willis. The process depends on the light sensitivity of iron salts to create an image. Chemical reactions exploited during developing, however, dissolve out the iron salts and replace them with platinum. Platinum prints were popular until the 1920's when the price of platinum rose so steeply that they became too expensive. They were valued for their great range of subtle tonal variations, usually silvery greys, and their permanence. Recently platinum prints have enjoyed a revival for fine art photography.

Polaroid

An instant film, giving an almost immediate positive print.

Radiograph

Radiography is the imaging technique using X-rays that pass through an object and are captured directly behind it on photographic film, or, more recently, on digital sensors. The first X-ray images were made in Germany by Wilhelm Röntgen in late 1895.

Salt print

Salt prints were the earliest positive prints and were invented by William Henry Fox Talbot in 1840, as a direct development from his earlier photogenic drawing process. A salt print was made by soaking a sheet of paper in salt solution and then coating one side with silver nitrate. This produced light sensitive silver chloride in the paper. After drying, the paper was put directly beneath a negative, under a sheet of glass, and exposed to sunlight for up to two hours. Salt prints were made until about 1860 having been gradually replaced by the albumen print which gave a clearer image although the process was sometimes revised later.

Scannergram (scanography)

The process of directly capturing digitized images of objects uses a flatbed ‘photo’ scanner. Commercial flatbed colour scanners were intended to copy paper documents, but they became increasingly available and affordable in the 1990s and led to experimentation by artists. The scanner’s limited depth of field means that three-dimensional objects placed on it only appear in focus about 12 mm from the surface, yet the image resolution is comparatively high compared with standard digital camera capture.

Woodburytype

The Woodburytype was a form of photomechanical reproduction of a photograph patented in 1864 by Walter Bentley Woodbury. Despite the painstaking care required, it remained popular until about 1900 because of the very high quality of the final image. This image was formed in pigmented gelatin rather than ink, with thicker or thinner areas of gelatin giving darker or lighter tone. The result was a reproduced image that was very true to the original and highly luminous.