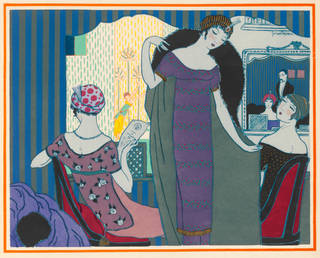

Designer Paul Poiret (1879 – 1944) led the fashion world in the first decade of the 20th century. This extract from his 1931 autobiography, 'King of Fashion', tells of his meteoric rise to fame, designing dresses for the esteemed Parisian couturier, House of Worth.

At the end of my military service, I thought of returning to my habitual occupations, and I wanted to get into dressmaking again. The best way of getting back into touch with the great houses was to become a designer once more. I returned to my former clients, and especially M. Worth.

The Maison Worth at that time was directed by the two sons of the great couturier who had dressed the Empress Eugénie. They were called Jean and Gaston. It was Gaston who made me the following proposition:

"Young man, you know the Maison Worth, which has always dressed the Courts of the whole world. It possesses the most exalted and richest clientèle, but today this clientèle does not dress exclusively in robes of State. Sometimes Princesses take the omnibus, and go on foot in the streets. My brother Jean has always refused to make a certain order of dresses, for which he feels no inclination: simple and practical dresses which, none the less, we are asked for. We are like some great restaurant, which would refuse to serve aught but truffles. It is, therefore, necessary for us to create a department for fried potatoes."

I perceived immediately what interest I might have in becoming the potato frier for this great house, and I at once accepted the position that was offered me. Its terms were, in any case, most flattering, and I began to make models that were severely criticised by the vendeuses (saleswomen), who reminded me of the Furies at Doucet's, but which pleased the public.

I got to know a type of dress that I had never before met with. I wanted to know everything that had been done before me, and several times I examined all the models successively. I even looked through the albums which told of the exuberances of good Father Worth the couturier of the Tuileries. They were full of samples and water-colour sketches, which spoke eloquently of the taste of the Court of the Empress. I especially remember a crinoline dress whose whole lower part was of telegraph wire, forming girandoles around which stuffed swallows flew and came to rest.

Another dress of the same period was garnished with great embroidered snails. I did not try to approximate my style to that of the House, but I must say that it had very much evolved, and that the dresses which came from the hands of M. Jean were models of art and purity. He worked a great deal after the pictures of the old masters, and I have seen him derive magnificent ideas from the canvases of Nattier and Largillière. He was surrounded by very highly skilled women, and by one, in particular, who moulded corsages as in the Great Century, out of plain or figured satin, which stood up stiff like armour, giving at the waist in charming folds to disclose the suppleness of the thighs. And he would make a sleeve out of a long tulle scarf held above the elbow by a row of diamonds and finished by two emerald tassels. (For he could not conceive that a dress could be made without some opulence). I can understand very well why my little man-in-the-street lucubrations seemed to him wretched and puny.

M. Jean Worth was not very pleased at having introduced into his House an element which, in his opinion, lowered it. He did not like me very much, because in his eyes I represented a new spirit, in which there was a force (he felt it) which was to destroy and sweep away his dreams. When I was showing him a model, a little tailor-made, I saw him suddenly pale, as if he were going to be ill (he was extraordinarily nervous) and he pronounced, standing before his customary audience of obsequious courtiers, the following words:

"You call that a dress? It is a louse."

And I, lest he should enlarge upon his theme, went off to hide my shame in my office. But this louse made its own way, and sold many times over; there must have been stormy arguments about me between the two brothers. I felt that I was hated by the one, supported by the other. Gaston Worth, who thought only of commercial results, foresaw the present day, and the threat that already overhung the Courts of Europe.

One day the House was filled with red velvet, and no other word was heard but Crimson. It was the colour of the cloaks of State at the Court of England, and the forthcoming coronation of Edward VII had been announced. M. Jean Worth proudly showed me a notice received from the English Court, describing the etiquette. All the nobility wore, according to their titles and precedence, longer or shorter trains, and more or less numerous ermine borders. For three months we made nothing but Court mantles. They were distributed throughout every room in the House, for one could not think of working on tables these fragile velvets, woven according to secular tradition – they would have been ruined if they had been pulled about. They were therefore placed over wooden mannequins, and their trains pinned to the floor; swarms of workwomen circled about them, working at pressure but meticulously, like arch-deacons around some holy relic. M. Worth showed everyone these hieratic masterpieces, which to him seemed to represent the superlative of beauty. He exulted. I must avow, with shame, that I never understood what he found admirable about them. I compared these conventional get-ups with the red, gold-fringed draperies held high by the Maison Belloir over important marriages, or distributions of prizes, in municipal ceremonies.

One day M. Worth was looking out of the window in the Rue de la Paix; he loved to see the coming and going of the carriages that brought to him the flower of the whole world. It was his familiar custom. Suddenly he turned round as if a spring had been released, saying:

"Mesdames, Princess Bariatinsky!"

And I saw that his heart was beating more quickly.

All the vendeuses rose with one movement, the chairs were ranged along the wall, as if for a revue, and everybody went toward the landing stage outside the lift. From every corridor there came forth members of the staff, who had been hastily informed. The whole House was on deck, in front of the door, and M. Worth stifled with his hands the barks of the little dog he was holding under his arm and which, stirred by the commotion, wanted to take part in the general rejoicing. I was at the end, curious to see the beautiful Princess who was the cause of this sensation. The lift took an immense time to come up, doubtless it was bearing a heavy weight. When it arrived at the landing, I was disillusioned to see in its interior nothing but a sort of fat little curate, black clad, with congested face, bent double over two sticks, and smoking a big cigar. Everyone bowed or curtseyed. M. Worth prostrated himself. The Princess, in a voice full of assurance, said to him with the most perfect Russian accent:

"Worth, show me your confections."

It was thus that she referred to the gowns.

M. Worth most obsequiously made her sit down, while the mannequins appeared with speed, and I had the honour of showing the Princess a cloak I had just finished, and which was then a novelty. Today it would seem banal, almost outmoded, but then nothing like it had been seen. It was a great square kimono in black cloth, bordered with black satin cut obliquely; the sleeves were wide right to the bottom, and were finished with embroidered cuffs like the sleeves of Chinese mantles. Did the Princess have some vision of China, which for Russia bore a hostile face? Did she see Port Arthur, or something other? I know not, but she cried out:

"Ah! What a horror; with us, when there are low fellows who run after our sledges and annoy us, we have their heads cut off, and we put them in sacks just like that . . ."

I already felt that my head was in the sack. I disappeared, cast down and despairing of ever pleasing Russian Princesses.

Soon after that an opportunity presented itself whereby I could make, in Paris, the dresses I best liked for the women I most esteemed. Premises in the Rue Auber were falling vacant. And a vendeuse from a neighbouring House was also about to be disengaged. I began to feel my wings spread, I had followed the advice of M. Doucet, and I had taken a pretty mistress, who was much remarked for the elegance with which I decked her out; I would try my luck.

One day I arrived from Auvers in M. Gaston Worth's office, and I said to him:

"You asked me to create a department for fried potatoes. I have done it. I am satisfied with it, and I hope you are too. But it spreads through the House an odour of frying, which appears to incommode a great many people. I therefore think of setting up for myself in another quarter, and frying chips on my own account. Will you pay for my frying pan?"

M. Worth smiled, and said he understood my impatience, and he congratulated me on my initiative, but he could not dream of taking an interest in any other business but his own, and in the pleasantest way in the world he wished me good luck.

The complete King of Fashion: The Autobiography of Paul Poiret is now available in the V&A Fashion Perspectives e-book series from online retailers.