What makes Julia Margaret Cameron's work so highly regarded today? Discover her working methods and the personal touches that make her style of portrait photography so unique.

Julia Margaret Cameron was 48 when she received her first camera, a gift from her daughter and son-in-law. She soon transformed her home to accommodate her new pursuit:

I turned my coal-house into my dark room, and a glazed fowl-house I had given to my children became my glass house!

Before then, Cameron had compiled albums and experimented with printing photographs from negatives. On one occasion she printed a negative by the pioneering Swedish art photographer O.G. Rejlander, surrounding the portrait with ferns to create a photogram frame – a combination of an image made in a camera and a camera-less technique. It shows Cameron's experimental nature and provides a glimpse of her photographic practice before she acquired a camera of her own.

When Cameron took up photography, it involved hard physical work using potentially hazardous materials. The wooden camera, which sat on a tripod, was large and cumbersome. She used the most common process at the time, producing albumen prints from wet collodion glass negatives. The process required a glass plate (approximately 12 x 10 inch) to be coated with photosensitive chemicals in a darkroom and exposed in the camera when still damp. The glass negative was then returned to the darkroom to be developed, washed and varnished. Prints were made by placing the negative directly on to sensitised photographic paper and exposing it to sunlight.

Each step of the process offered room for mistakes: the fragile glass plate had to be perfectly clean to start with and kept free from dust throughout; it needed to be evenly coated and submerged at various stages; the chemical solutions had to be correctly and freshly prepared.

Yet Cameron quickly devoted herself to photography and within a month of receiving her camera, she made the photograph that she called her 'first success', a portrait of Annie Philpot, the daughter of a family staying in the Isle of Wight where Cameron lived. She later wrote of her excitement:

I was in a transport of delight. I ran all over the house to search for gifts for the child. I felt as if she entirely had made the picture.

From her 'first success' she moved on quickly to photographing family and friends. These early portraits reveal how she experimented with soft focus, dramatic lighting and close-up compositions, features that would become her signature style.

From life not enlarged

In the summer of 1865, Cameron began using a larger camera, which held a 15 x 12 inch glass negative. She used her new camera to begin a series of large-scale, close-up portraits, which she saw as a rejection of conventional photography in favour of a less precise but more emotionally compelling kind of portraiture. She wrote to Henry Cole, the director of the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A), that she intended this new series to "electrify you with delight and startle the world".

One photograph in this series, entitled Head of St. John, was a portrait of Cameron's niece May Prinsep. Lit from the side, with her hair loose, Prinsep appears androgynous, like a male saint. Cameron inscribed this photograph, 'From life not enlarged', to emphasise that the head was nearly life-size.

Cameron also produced a series of 12 life-size studies of children's heads with her new camera. These were intended as artistic studies, made with intensity and tenderness.

Her mistakes were her successes

Cameron included imperfections in her photographs – streaks, swirls and even fingerprints – that other photographers would have rejected as technical flaws. Although criticised at the time, these imperfections can now be appreciated as ahead of their time. In her work Iolande and Floss, for example, swirls of collodion used during the photographic process merge with the swirls of drapery, enhancing the dreamy, ethereal quality of the image.

We don't know if Cameron herself embraced these 'flaws' or if she simply tolerated them. We do know, however, that she sometimes scratched into her negatives to make corrections; printed from broken or damaged negatives and occasionally used multiple negatives to form a single picture, which tells us that she didn't mind a certain level of visible imperfection, at the very least.

One of her most extreme examples of manipulating a negative can be seen in a portrait of Julia Jackson. Cameron scratched a picture into the background of this pious portrait of her niece, to create a hybrid photograph-drawing. The drawing of a draped figure in an architectural setting evokes religious art.

She was not happy, however, with one type of imperfection: the appearance of cracking. She wrote to Henry Cole complaining that cracking had ruined some of her most "precious negatives", including a photograph entitled The Dream. She blamed her photographic chemicals for the cracks, while members of the Photographic Society suspected the damp climate of the Isle of Wight. Today's theory is that a failure to thoroughly wash the negatives after fixing them caused the cracking. She seemed not to be bothered, however, by the two smudged fingerprints in the lower right of The Dream.

Defective impressions

Our Julia Margaret Cameron collection includes 67 photographs that once belonged to her friend and mentor, the artist G. F. Watts. Watts wrote to Cameron:

Please do not send me valuable mounted copies… send me any… defective unmounted impressions, I shall be able to judge just as well & shall be just as much charmed with success & shall not feel that I am taking money from you.

His request for "defective unmounted impressions" explains why this group includes numerous examples of Cameron at her most experimental: figures stand out starkly against black backgrounds caused by missing collodion, faces swim in swirling chemical mists, or are framed by the lines of a cracked negative. Many are unique, which suggests that Cameron was not fully satisfied with them.

Viewed alongside those prints that we acquired from Cameron herself, the photographs she sent to Watts shed light on Cameron's working process and personal standards. They can be understood as unfinished sketches that she sent to Watts for comment as part of her process. The very 'defectiveness' of these prints suggest Cameron was a more discerning artist than assumed by critics, both in her own time and after.

Portraits, Madonna groups and fancy subjects

Cameron described her photographic subjects in the categories 'Portraits', 'Madonna groups', and 'Fancy Subjects for Pictorial Effect'.

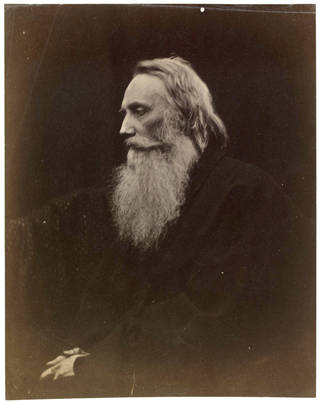

For portraits, she often photographed her intellectual heroes such as Alfred Tennyson, Sir John Herschel and Henry Taylor, saying that she wanted to record "the greatness of the inner as well as the features of the outer man". Selling prints of these photographs also offered the opportunity to earn money, since her family's finances were precarious. Within her first year as a photographer, she began exhibiting and selling through the London gallery Colnaghi's, where she used the subjects' autographs to increase the value of some portraits.

One of Cameron's earliest celebrity portraits is of Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Poet Laureate and one of the most famous writers in England at the time. He was also Cameron's close friend and neighbour on the Isle of Wight. Tennyson moved slightly during the exposure, resulting in a doubling that gives the portrait a sense of vitality.

Another prominent sitter was the naturalist Charles Darwin, who had rented a cottage with his family on the Isle of Wight from the Camerons in the summer of 1868. Due to his celebrity, Cameron later had this portrait reprinted as a more stable carbon print.

The largest proportion of Cameron's portraits still featured members of Cameron's family and household. The powerful portrait of her niece and goddaughter Julia Jackson, depicted as herself, rather than a religious or literary character, is one of a series of portraits in which the dramatically illuminated Jackson fearlessly returns the camera's gaze.

In contrast to her portraiture of individuals, Cameron looked to painting and sculpture as inspiration for her allegorical and narrative subjects. She made some works as photographic interpretations of specific paintings by artists such as Raphael and Michelangelo. In others she aimed to create more generally what she described as 'pictorial effect'.

In aspiring to make this kind of 'high art', she also wanted to make photographs that could be uplifting and morally instructive. She was a devout Christian and also a mother of six, so the motif of the Madonna and Child was particularly significant for her.

The South Kensington Museum purchased many of Cameron's 'Madonna groups', depicting visions of the Virgin Mary and the infant Christ. Her housemaid Mary Hillier posed as the Virgin Mary so often that she became known locally as 'Mary Madonna'.

When she acquired her larger camera in 1865, Cameron continued to make narrative and allegorical tableaux, which became larger and bolder than her previous efforts. Her maid Mary Ryan posed as the title character of Tennyson's poem 'The May Queen' in the photograph May Day, which shows the English rural custom of crowning a young girl as Queen of the May on the first of that month. Cameron would later revisit this theme in two volumes of illustrations to Tennyson's poems.

Throughout her career, Cameron continued to work interchangeably between portraits, Madonna groups and 'fancy subjects for pictorial effect', moving comfortably between photographing her wider social circle and her closer world, including members of her family and household. Our collection of Cameron's prints is representative of her wide range of subject matter as well as the forward-looking and experimental nature of her working process.

Discover more about Julia Margaret Cameron.