William Morris is best known as the 19th century's most celebrated designer, but he was also a driven polymath who spent much of his life fighting the consensus. A key figure in the Arts & Crafts Movement, Morris championed a principle of handmade production that didn't chime with the Victorian era's focus on industrial 'progress'. Our collections hold a huge amount of his work – not only wallpapers and textiles but also carpets, embroideries, tapestries, tiles and book designs.

Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.

Morris was born in Walthamstow, east London in 1834. The financial success of his broker father gave Morris a privileged childhood in Woodford Hall (a country house in Essex), as well as an inheritance large enough to mean he would never need to earn an income. Time spent exploring local parkland, forest and churches, and an enthusiasm for the stories of Walter Scott, helped Morris develop an early affinity with landscape, buildings and historical romance. He also had precociously strong opinions on design. On a family trip to London in 1851, Morris (then aged 16) demonstrated his loyalty to craft principles by refusing to enter the Great Exhibition – which championed Machine Age design – on the grounds of taste.

After school, Morris went to Oxford University to study for the Church. It was there that he met Edward Burne-Jones, who was to become one of the era's most famous painters, and Morris's life-long friend. Burne-Jones introduced him to a group of students who became known as 'The Set' or 'The Brotherhood', and who enjoyed romantic stories of medieval chivalry and self-sacrifice. They also read books by contemporary reformers such as John Ruskin, Charles Kingsley and Thomas Carlyle. Belonging to this group gave Morris an awareness of the deep divisions in contemporary society, and sparked his interest in trying to create an alternative to the dehumanising industrial systems that produced poor-quality, 'unnatural' objects.

In 1855, Morris and Burne-Jones went on an architectural tour of northern France that made both men realise that they were more committed to art than the Church. Soon after, Morris began work in the office of George Edmund Street, the era's leading Neo-Gothic architect. Morris showed little talent for architecture and spent most of his time setting up Oxford and Cambridge Magazine, a vehicle both for his own writing and that of other members of The Brotherhood. Morris left Street's office after only eight months, to begin a career as an artist. Burne-Jones's connection with the artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti – a central figure in the Pre-Raphaelite group – soon led to Morris working with Rossetti as part of a team painting murals at the Oxford Union.

While working in Oxford Morris had a chance meeting with a local stableman's daughter, Jane Burden. Consciously flouting the rules of class, Morris married Jane in 1859 (and her striking looks were to make her a model of idealised beauty for members of the Pre-Raphaelite group for the next 30 years). Morris commissioned architect Philip Webb – whom he had met during his time at Street's – to design and build a home for himself and his wife in rural Kent. In part, Morris wanted to realise the idea of a craft-based artistic community that he and Burne-Jones had been talking about since they were students. The result was Red House, a property that would be 'medieval in spirit' and, eventually, able to accommodate more than one family.

Morris and Jane moved into Red House in 1860 and, unhappy with what was on offer commercially, spent the next two years furnishing and decorating the interior with help from members of their artistic circle. Huge murals and hand-embroidered fabrics decorated the walls, creating the feel of a historical manor house. Prompted by the success of their efforts (and the experience of 'joy in collective labour'), Morris and his friends decided in 1861 to set up their own interiors company: Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. Everything was to be crafted by hand, a principle that set the company firmly against the mainstream focus on industrialised 'progress'.

Initially, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. specialised in the kind of wall paintings and embroidered hangings that had been produced for Red House. Although in its first few years the company didn't make much money, it did win a series of commissions to decorate newly built churches, and became well known for work in stained glass. Morris had always wanted the firm to be based at Red House but the practical restrictions of a small, rural workshop (as well as the death of Burne-Jones's young son) meant that the idea of a medieval-style craft-based community was abandoned. Morris sold Red House in 1865 and the family moved back to London.

In the late 1860s, two prestigious decorating commissions helped establish Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co.'s reputation: one for a new dining room at the South Kensington Museum (later the V&A), and another at St James's Palace. During this period, Morris was also working on The Earthly Paradise, an epic poem with an anti-industrial message that established Morris as one of the foremost poets of his day. He was also busy producing his first wallpapers, whose designs were inspired by English gardens and hedgerows. To make them, he researched and revived historical printing and dyeing methods. This insistence on establishing a 'from scratch' understanding of process was to become a hallmark of Morris's career.

In 1875 Morris became sole director of the renamed and restructured Morris & Company. Over the next decade he continued to design at an impressive rate, adding at least 32 printed fabrics, 23 woven fabrics and 21 wallpapers – as well as more designs for carpets and rugs, embroidery and tapestry – to the company's range of goods. All of these were sold in the shop that Morris opened on Oxford Street in 1877, in a fashionable space that offered a new kind of 'all under one roof' retail experience. By 1881 Morris had built up enough capital to acquire Merton Abbey Mills, a textile factory in south London. This allowed him to bring all the company's workshops together in one place, and to have closer control over production.

In his political life Morris became increasingly disillusioned with parliamentary politics as a means of ending class division, and in 1884 he helped set up a new group called the Socialist League. He made frequent street-corner speeches and went on marches, but his fame protected him against the sanctions of a disapproving establishment. Increasingly, Morris began to leave matters at Merton Abbey in charge of his assistant Henry Dearle and other senior members of the firm, including his daughter, May. He did however continue his interest in tapestry, and for the last five years of his life was involved with Burne-Jones and Dearle on the design of a set of panels based on the Search for the Holy Grail.

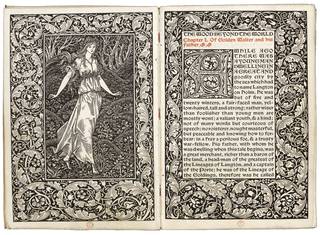

Towards the end of his career, Morris began to focus increasingly on his writing, publishing a number of prose narratives, including his most celebrated: News from Nowhere (1890). Infused with his socialist ideas and romantic utopianism, this book offers Morris's vision of a simple world in which art or 'work-pleasure' is demanded of and enjoyed by all. In 1891 (the same year he turned down the Poet Laureateship after the death of Tennyson), Morris set up the Kelmscott Press. The books the Press produced – eventually, a total of 66 – were printed and bound in a medieval style, with Morris designing their typefaces, initial letters and borders. The most famous of these is an illustrated edition of the works of Geoffrey Chaucer, which was published in 1896, a few months before Morris's death.

Find out more in the book News from Nowhere, written by William Morris.

Read more about Morris in our comprehensive illustrated book, with chapters on painting, church decoration and stained glass, interior decoration, furniture, tiles and tableware, wallpaper, textiles, calligraphy and publishing.