How people live, work, travel, consume and communicate have changed in extraordinary ways since 1900. Designed objects help us understand these changes and prompt us to ask questions about the past, present and future.

A robot as my colleague?

The first decades of the 20th century saw vast changes in how goods were manufactured. The introduction of the first moving assembly line at Ford Motors in 1913 dramatically altered the way things were made. Mechanised production had a direct impact on workers, with more repetitive work on the one hand and incentives like higher wages and the first paid holidays on the other. How things were designed also shifted. Simpler shapes and fewer decorative features made manufacturing more efficient, as is the case with the Luterma luggage, produced in Estonia from the early 1900s. Objects inspired by the new possibilities of the machine emerged, even if they were not always machine-made. Designs coming out of the Bauhaus, the trailblazing German art school, in the 1920s demonstrates this.

How and where we work has also transformed since the beginning of the 20th century. Automation in the early 1900s boosted productivity in factories. And today, computers, robotics and smart devices have reshaped habits and working patterns. In some factories wearable computers provide employees with automated instructions on which products to collect, scan and pack.

Increased connectivity has also shaped where we work, with many now working away from the office. During the Covid-19 pandemic the challenge has broadened to include the new demands of remote working and setting up offices in the home. In these fast-changing conditions, designers' attention has turned to what businesses and workers need: from products to maximise efficiency and profit, to those that create healthier working environments.

How do you create housing for all?

In the 1920s, a new international movement known as Modernism sought to reinvent society through the design and architecture of the home and the city. Modernist architect Le Corbusier wrote: "The house is a machine for living in" and books including Erna Meyer's The New Household (1926) looked to automation in factories to suggest ways of optimising productivity in the home.

The efficient, affordable home became a key subject of debate at this time and initiatives such as the affordable public housing programme 'New Frankfurt' in Germany resulted in over 10,000 new homes built between 1925 and 1930. The so-called Frankfurt Kitchen by the architect Margrethe Shütte-Lehotsky was designed for this development and has shaped the way compact kitchens have been designed throughout the 20th century and into the 21st.

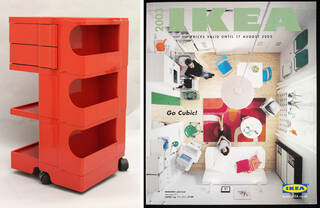

Today, over half the world's population lives in urban areas, a figure expected to climb to two-thirds by 2030. As in the early 1900s, this dramatic expansion has generated the urgent need for more homes, and designs that make compact living possible. The Boby trolley by Joe Columbo from 1970 is one such example. While the Ikea 'Go Cubic' catalogue from 2003 is a more recent expression of the same issue.

How can crisis shape design?

The two World Wars and rationing, the Cold War and nuclear threats, the 2008 financial crisis, the Covid-19 pandemic and growing inequality are just some of the issues we have faced as a society over the last 120 years. In times of need, design is an exercise in problem-solving. When money or resources are scarce, designers and makers seek innovative solutions and push for change. In 2015, residents from Granby, a neighbourhood in Liverpool, co-founded Granby Workshop with the London-based architecture collective Assemble. Producing ceramics, stoneware and textiles, it is a social enterprise supporting the community through making, with all proceeds being reinvested in the local area.

The Janma Clean birthing kit provides the tools required for a safe childbirth. It was designed for distribution in rural and poor communities where pregnant women do not have easy access to hospitals or medical assistance.

In 2020, the UN estimated that the world had more than 270 million migrants. Almost 70 million of these were refugees or displaced people, forced to flee due to conflict or a changing climate. This scale of mass movement is the largest it has been since the Second World War. Better Shelter is an initiative that provide flat-packed steel-frame shelters for displaced people living in temporary accommodation for extended periods of time. More durable and secure than a tent, it can be built within four hours without specialist tools.

How does design add value?

In the 20th century, many international companies started to recognise that design was an important part of building a brand. They brought designers on board to make their goods more efficient, luxurious and even fun. The rise of advertising has also helped to fuel materialism. As the century progressed, advertising agencies increasingly began to promote alluring lifestyles and branded products to sell new consumer products to targeted audiences.

In the 1970s graphic designer Thomas Miller of Morton Holdsholl Associates temporarily redesigned the logo of drinks brand 7Up to evoke the can's fizzy content. His visually impactful packaging design and the promotional campaign, which included a radio in a can, successfully boosted 7Up's appeal and increased sales.

What we consume and how we show it also allows us to control how we present ourselves to others. Through our choices, we can conform to society's expectations, or break free from a set of prescribed, and to some restrictive, ideals. The Mae West Lips sofa designed by Salvador Dalí and his patron Edward James from 1938 is an extravagant example of breaking free from these norms. It formed part of a movement of Surrealism in art and design.

When did design become sustainable?

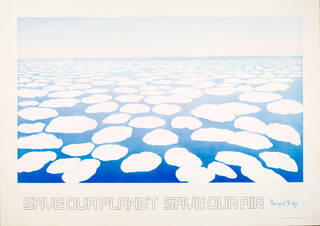

The 1960s saw a growing concern about the impact of industry and large-scale agriculture on the planet and its inhabitants. This kick-started environmental awareness with the first Earth Day staged in the US on 1 April 1970, and a number of popular poster campaigns captured this moment of collective concern.

Olivetti, the computer and typewriter manufacturer, issued a series of posters by famous artists around this time, to push for more consciousness around the environment.

As the 20th century came to a close, many designers, artists and architects reflected this change of mood, becoming more socially, politically and environmentally conscious. They subverted established norms by offering up critical and playful commentaries on society through alternative and radical propositions for new ways of living. This gave rise to movements such as Memphis and Postmodernism, which rejected prevailing design norms shaped by Modernism.

Others, motivated by a concern for the planet, focused on finding eco-friendly solutions for how their products were made and consumed. The Body Shop is a well-known example to come out of this moment.

Yet heightened awareness of how our choices take their toll on the world's natural resources and ecosystem has in recent decades led to artists and designers looking to reuse waste and develop alternative materials. These environmentally sustainable approaches are promising steps towards a zero-waste culture. The Flax chair by Christien Meindertsma is produced from a board made from flax and bioresin and is biodegradable. While the Katran chair uses discarded textiles to create a colourful woven seat.

Who owns my data?

Our world has opened up in unimagined ways in the 21st century. High-speed broadband, smartphones, social media and machine learning are radically reshaping how we interact and communicate across the globe.

The Chinese app WeChat has pioneered new ways of communicating digitally in the 2010s, popularising the use of animated GIFs called 'stickers' as a simple way of conveying emotions.

Digital technologies offer immense freedom and opportunity – but with this comes a shared responsibility for how they are used and regulated. Telecommunication systems and the introduction of radio broadcasting in the 20th century enabled us to speak across distances and send news around the globe. But with this came the opportunity for individuals, corporations, and governments to listen in.

The Kalighat painting by Kalam Patua from 2009 depicts these concerns by portraying a woman disappearing in to the night with her mobile phone in hand, the glowing light of the screen revealing her whereabouts to the man watching from the window.

At moments of heightened political tension, designers have created devices, software and apps to gain greater or covert access to individuals' information. Yet at the same time, others have devised pro-privacy objects that act as barriers to this encroachment, such as the USB condom designed to prevent the accidental release of personal information while charging your digital devices publicly.

Today, the computers and smartphones we use, the gadgets we wear, the websites we browse and the apps we download are all designed to gather data and track our habits. It has led to a new self-awareness that is both insightful and, at times, intrusive. The Fitbit demonstrates this well, by tracking your resting and activity habits, leading to what is now termed "the quantified self".