Africa is home to an abundance of cloth types, encompassing a breadth of materials and techniques as diverse as the continent itself. Revered for their distinctive weaving, dyeing, and decorative processes, as well as the raw materials used, these cloths are the tactile result of centuries of technical skill, knowledge and self-expression that remains alive to this day. Far from static, these cloths are the focus of constant re-invention and re-imagination, with artisans adapting them to suit contemporary tastes, introducing new patterns, new fibres, and new dyes.

Whether fashioned into tailored clothes or draped in uncut lengths, cloth envelopes the body in a visual display that adorns and signifies through colour, pattern and texture. Invoking a specific sense of place, a cherished heritage, a memory or a feeling, they reveal the many layered histories of the continent and the cultural exchanges within. Their ability to embody countless stories and histories, from the personal to the political, lends cloth a particular gravitas felt by many across the continent and diaspora. As the sculptor El Anatsui once said, echoing fellow artist Sonya Clark, "Cloth is to the African what monuments are to Westerners".

Though by no means exhaustive, numerous examples of cloth from the continent exist in the V&A's collections, representing many of the innovations, evolutions, and continuations of Africa's long textile tradition.

Àdìrẹ

Àdìrẹ is an indigo-dyed cloth traditionally produced by Yoruba women in south-western Nigeria. A range of resist-dye techniques are used to create àdìrẹ patterns, often incorporating more than one technique in a single cloth. The ground-cloth cotton is folded, stitched, tied or otherwise worked-upon in preparation for dyeing – these areas resist the dye, creating the cloth's distinctive blue and white patterns. The precise origins of àdìrẹ are unknown, though indigo-dyeing has been seen across West Africa for centuries. Àdìrẹ has an enduring presence in the region, becoming a popular, everyday cloth, with many women dyeing àdìrẹ of their own design within the home. Once dyed, àdìrẹ cloth can be wrapped or stitched to create garments, such as a woman's ìró (wrapped skirt). From the 20th century onwards, factory-woven cloth began to be used – this cloth accepted the dye more easily, creating a finer clarity of design. Whilst factories are now able to mass-produce imitation àdìrẹ, the popularity of the traditional hand-worked cloth remains, made by local artisans in historic dyeing centres such as Ibadan.

Today, àdìrẹ is undergoing another revolution, popularised by fashion brands such as Maki Oh, Lagos Space Programme and Orange Culture, it has become a staple on the catwalk and in our wardrobes.

Àdìrẹ is subcategorised according to the method of resist-dyeing used, each of which carries its own history and produces its own recognisable effect:

- Àdìrẹ alábẹ́rẹ́ relies upon stitching as a means of resist-dyeing. This is achieved by folding and stitching down the cloth, or by stitching designs directly onto it and removing the thread after dyeing. Stitching can be done by hand, using either raffia or cotton thread. In more recent times, machine-stitching with cotton thread has become more common.

- Àdìrẹ ẹlékọ is often seen as the most recently developed àdìrẹ technique, using a cassava starch paste as the resist. This is applied with a brush or feather using either a meticulously cut metal stencil, or, painted freehand onto the cloth – the latter providing the opportunity for more stylised and complex designs.

- Àdìrẹ oniko uses tied raffia thread to create the resist-dyed pattern, in what is probably the oldest àdìrẹ technique to emerge. Prior to dyeing, sections of the cloth are manipulated by pleating, folding or gathering the cloth and tying it tightly with raffia. A secondary method sees the cloth wrapped around a small object – such as a stone or stick – and then tied with the raffia. Eleso is a specific variation of àdìrẹ oniko, whose circular pattern is created by seeds which act as the resist.

Find out more about àdìrẹ.

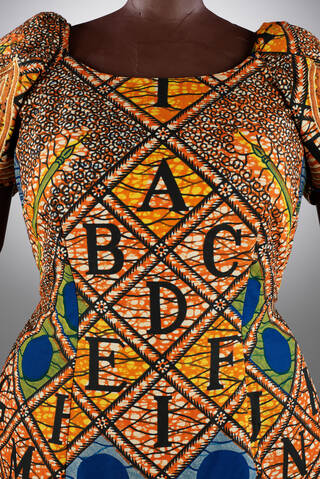

Ankara

Ankara is a printed cotton cloth, produced in a variety of patterns formed by the layering of polychromatic dyes. Fashionable in West and East Africa since the late 19th century, ankara is variously known as 'African wax' or 'Dutch wax' print – despite wax rarely being used in its manufacture. Embodying the overlapping colonial interests that prevailed in the region and beyond, the cloth has a complex history – rooted in trade monopolisation and cultural appropriation, yet acting as a conduit for African agency and resistance.

Originally produced in the Netherlands, ankara emerged from experiments to mechanically replicate batik, an Indonesian wax-print cloth traditionally developed by hand. Early Dutch attempts roller-printed a resin-resist onto both sides of the cloth before dyeing; the resist was then washed out, with additional layers of colour added by repeating this process, hand-blocking and/or roller-printing. The intended export market of Indonesia did not respond well to this imitation batik, as the resin was prone to cracking and bubbling, producing defects in the print. A keen market for the cloth did, however, emerge across West Africa in the 1890s, such that several factories – chiefly in Britain and the Netherlands – began producing ankara with this new customer in mind. Responding to market feedback on popular colours and patterns, European producers adapted ankara designs to suit the tastes of their discerning West African customers. In a collaboration between the consumer, dealer and manufacturer, local sellers would inform European merchants which styles were in demand and suggest motifs that would likely sell well.

By the early 20th century, a cheaper and more refined method of ankara production had been developed, roller-printing only one side of the cloth with a design, without the use of a resin-resist. Many examples of this later ankara purposefully include the imperfections that originally marred Dutch attempts to replicate batik – alluding to the more esteemed resin-resist technique.

Decades after its arrival, independence from colonial rule saw the production of ankara relocate to the continent, when African competitors established their own rival businesses. Ankara designs during this time often featured political symbols and slogans, celebrating a new era of independence. For many, ankara remains a powerful signifier of West African identity, reinforcing personal style and national pride. The ensemble in our collection featuring the alphabet was tailored in the 1990s, using ankara purchased in Ghana by the wearer. The ABC pattern can be traced back to at least the 1920s and alludes to the value of education. Contemporary fashion designers such as Christie Brown and Lisa Folawiyo continue to spotlight ankara within their work, reimagining the cloth for a contemporary consumer through innovative tailoring techniques and additional embellishment.

Aṣọ-òkè

Aṣọ-òkè is a handmade strip-woven cloth historically produced by the Yoruba in south-western Nigeria. Stripweave is an ancient textile type created by stitching together individual, narrow strips of handwoven fabric to form a whole finished cloth. Locally sourced silk and cotton has historically been hand-spun, dyed and woven by the Yoruba in the production of aṣọ-òkè. Weaving is traditionally the domain of Yoruba men, who use a single-heddle loom to produce long strips around four inches wide. These are then cut and stitched together to create the prestigious aṣọ-òkè cloth.

Loosely translated as 'cloth from above' or 'cloth from the hill', the term aṣọ-òkè alludes to a revered past and the elevated status of the cloth. Aṣọ-òkè can be subcategorised as one of three major types; sányán, àlàárì or etù, which are distinguished by their use of colour, signifying the status, age or gender of the wearer:

- Sányán is a beige aṣọ-òkè associated with morality, woven with natural undyed silk, usually in combination with white cotton.

- Àlàárì is a deep red or magenta striped aṣọ-òkè of cotton or silk, whose colour suggests strength, bravery and protection from danger.

- Etù aṣọ-òkè is a dark blue and white striped or check cotton, whose use of indigo dye conveys the wealth, maturity and elevated status of its wearer.

Garments and textiles created from aṣọ-òkè serve a variety of functions, with certain pieces reserved for special religious, communal or family occasions. Worn by both men and women, aṣọ-òkè is typically striped, though this design may be supplemented by additional weft-float decoration. Occasionally, hand embroidery is added, as seen in the ensemble of sányán and àlàárì aṣọ-òkè created by Nigerian fashion designer Shade Thomas-Fahm, a notable advocate of Nigerian textiles.

Bògòlanfini

Bògòlanfini is a patterned cloth produced by the Banama of West Africa using vegetable dye and mud to create abstract patterns. Bògòlanfini – sometimes referred to as bòkòlanfini – employs a unique, multi-step discharge-dyeing technique that produces an off-white and brown patterned cloth. The ground of plain-weave cotton or wool cloth is typically woven by men, whereas women usually complete the dyeing process. Firstly, natural dye is used to colour the entire cloth yellow. Decoration is then hand-painted or stencilled on with an iron-rich mud solution, filling the background to create a negative-space pattern of geometric or stylised forms. This mud solution can be applied in layers to create a deeper tone of brown. Surplus mud is then removed, before the lighter areas of yellow are bleached out by carefully painting over the pattern.

Despite the cloth's decorative patterns being designed and created by women, bògòlanfini was historically predominantly worn by male hunters, and was thought to hold protective power. In the 1970s, Malian designer Chris Seydou began experimenting with bògòlanfini, using it in tailored ensembles, spearheading its use as a global fashion fabric. Over the following decades, the cloth became one of Seydou's design signatures, as he created his own bògòlanfini, abstracting traditional patterns in respect to their historic significance.

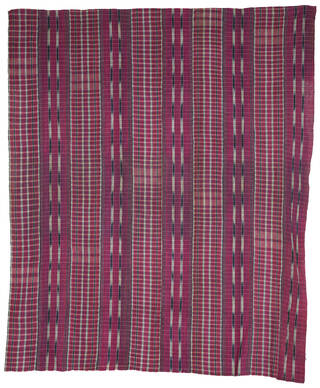

Ikat

The term 'ikat' is of Indonesian origin and is a technique of producing patterned cloth via the process of resist-dyeing yarn prior to weaving – an ancient technique found in many cultures around the globe. The resist pattern is achieved through tie-dyeing bundles of thread, typically with indigo, before weaving them – often in conjunction with other plain yarns. Most African ikats are warp ikats, whereby only the warp – and not the weft – is resist-dyed.

This example of Yoruba cloth is an aṣọ-òkè comprised of woven silk and plain and indigo-dyed cotton, which utilises the ikat technique to produce the blue and white vertical stripes.

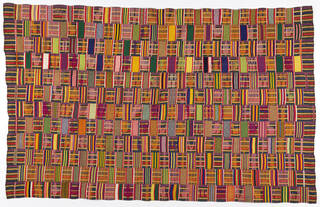

Kente

Formed by stitching together narrow strips of handwoven cloth, Kente often features colourful woven patterns. The term is particularly used to refer to the silk cloth of West Africa, where it has been traditionally crafted and worn by Asante and Ewe populations since at least the 17th century, chiefly in the region of modern-day Ghana. Stripweave is an ancient textile type, created by stitching together individual, narrow strips of handwoven fabric to form a whole finished cloth. Asante and Ewe men traditionally took on the role of weaving, using a small double-heddle handloom to make the cloth strips, typically warp-striped and often enhanced with weft-float patterns. These strips are arranged in an off-set manner of alternating patterns – the resulting effect is that of an elaborate design that if it were one continuous length would require a much larger and more complex loom. Historically the reserve of royalty and the elite, this highly prized textile is still today worn by many, often for important occasions and celebrations.

Different kente weaves, patterns and colours often hold special symbolic meaning. Many are given a particular name, usually assigned by the weaver, based on proverbs, current events, or everyday objects. It is possible to distinguish between Asante and Ewe kente through the types of pattern and fibres used – whilst Asante favour geometric patterns in silk, Ewe are known to include figurative motifs such as animals, people and letters in their weft-float designs, utilising a blend of cotton and silk. Whilst the names of individual weavers often go unrecorded, lost to history, one kente within the our collections bears a tantalising signature – possibly that of the weaver, or the cloth's commissioner.

Kuba

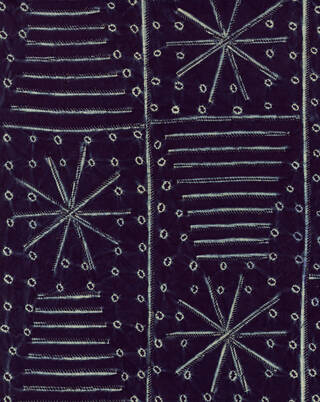

Kuba is a cloth of handwoven raffia palm fibres, often embroidered, dyed, appliqued or otherwise decorated in distinctive geometric patterns after the weaving process. Originating from the ancient Kuba kingdom of central Africa, the cloth is produced by the Kuba in the region that is today the Democratic Republic of Congo. The plain weave raffia ground of Kuba cloth is typically filled with a complex pattern of interlocking angular motifs. This is commonly achieved through a cut-pile technique using natural and dyed fibres. Designs are firstly stitched onto the cloth before raffia fibre is drawn through with a needle and closely cut to make a dense pile, creating a plush, velvet-like effect, as in the example pictured above. Areas of cut-pile can be complemented by uncut topstitch embroidery, again in raffia, adding to the textural interest of the cloth.

The production of Kuba cloth traditionally followed a gendered division – the ground cloth being woven by men using a single-heddle loom, whilst the decorative application of pattern by fine needlework was completed by women. At first glance, many Kuba cloth designs appear to bear regular repeat patterns. Irregularities are however the norm, thought to be a product of the individual embroiderer's inventiveness, as she introduces variety into the huge repertoire of existing named designs that are familiar to many. Once completed, Kuba cloth can be fashioned into garments or used within a domestic setting, acting as an indicator of status and wealth. In fact, the prestigious Kuba cloth was historically used as a form of currency within Kuba society.

Okene

A handwoven cloth, traditionally of cotton and bast (plant stem) fibres, produced by the Ebira in Central Nigeria. The cloth takes its name from the town of Okene, which historically acted as the central trading hub of the cloth. Typically woven by women in a domestic setting, okene cloth is produced on a vertical, single-heddle loom, at a rate of around five yards in a three-week period. Known locally as ita-inochi, okene cloth has a centuries-long history in the region, and by the middle of the 20th century the loom was still a common feature in most Ebira households.

Okene can be produced in plain cloth, but the vast majority exhibits a striped pattern, created by alternating warps of different colour. Additional visual interest may be added during the weaving process by the introduction of a supplementary weft-float pattern. Sold in sets of panels, okene can be stitched or wrapped into various garments for men and women. Indigo and white striped okene is, however, reserved for funerary cloth. Displayed around the home of the recently deceased and used as a burial cloth, the arrangement of the cloth's striped pattern varies according to the gender of the person being mourned.

Disclaimer

We have sought to use the correct accents and characters for words, but we are aware that common usage and standardisation can vary.