People had long been fascinated by the exotic nature of luxury products, such as porcelain, silk and lacquerware, that had been flowing into Europe from East Asia since the early 16th century. These imports stimulated Rococo designers of the mid-18th century to imitate and adapt oriental motifs and ornaments for a wide variety of objects. They didn't distinguish between what was Chinese, Japanese or Indian, but combined motifs to create an exotic fantasy world.

Chinoiserie is characterised by a number of frequently occurring motifs. In 18th-century Britain, China seemed a mysterious, faraway place. Although trade between the two countries had increased over the 17th and 18th centuries, access to China was still restricted and there were few first-hand experiences of the country. Chinoiserie drew on these exotic, mysterious preconceptions. Objects featured fantastic landscapes with fanciful pavilions, sweeping lines of the roofs of Chinese pagodas, fabulous birds and figures in Chinese clothes. Sometimes these figures were copied directly from Chinese objects, but more frequently they originated in the designer's imagination. Mythical beasts such dragons also became a common Chinoiserie motif, summoning up all that was strange and wonderful about the East.

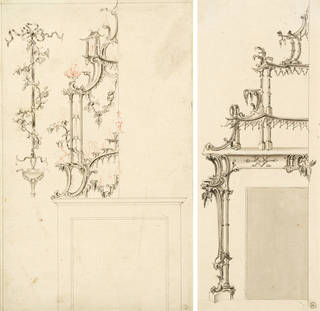

Publications like William Halfpenny's New Designs for Chinese Temples (1750) and Thomas Chippendale's The Gentleman and Cabinet-maker's Director (1754) helped to popularise the production of Chinoiserie furniture. The Director showed the full range of furniture available in the 18th century and the range of styles that were fashionable. Chippendale created a trademark fusion of Rococo style with Chinese and gothic elements, which was the basis of 'English' Rococo.

The designs in Chippendale's influential book were often imitated and adapted by other chair-makers, as is the case with this Chinoiserie-style chair whose overall form relates to Chippendale's designs, but includes other decorative details, such as small hanging bells.

More authentic designs were offered by Sir William Chambers (1723 – 96). Chambers is best known as a classical architect – inspired by the principles of Greek and Roman architecture of classical antiquity – but in his buildings he worked in a great variety of styles, including Chinoiserie. As a young man Chambers had travelled widely in the East, visiting the great Chinese port of Canton (Guangzhou). In 1757 he published a record of his observations in Designs of Chinese Buildings. Chambers designed a number of Chinoiserie buildings for the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew in London, including the first pagoda built in Europe (1761), an aviary and a bridge. These structures were not based on any real Chinese examples, but Chambers did aim for accurate imitations which contrasted with the fanciful creations of his contemporaries.

Chinoiserie motifs similar to those found on chinoiserie furniture and porcelain – pagodas, floral designs, and exotic imaginary scenes – also appeared on wallpaper during the 18th century. Chinese wallpaper first arrived for sale in London in the late 17th century as part of the larger trade in Chinese artefacts. Despite their cost, these Chinese papers were a popular amongst the upper and middle classes as decoration for bedrooms and apartments, especially those used by women. It was not surprising that English and French manufacturers soon sought to capitalise on this new fashion by producing imitations, which appear crude in comparison and inaccurate in their depictions.

Chinoiserie was not universally popular. Some critics saw the style as lacking logic and reason while others considered the style, with its inaccuracies and whimsical approach, to be a mockery of genuine Chinese art and architecture.

Interest in Chinoiserie continued into the 19th and 20th centuries but declined in popularity following the First Opium War of 1839 – 42 between Britain and China. China soon closed its doors to exports and imports and for many people chinoiserie became a fashion of the past.