The Aesthetic Movement in Britain (1860 – 1900) aimed to escape the ugliness and materialism of the Industrial Age, by focusing instead on producing art that was beautiful rather than having a deeper meaning – 'Art for Art's sake'. The artists and designers in this 'cult of beauty' crafted some of the most sophisticated and sensuously beautiful artworks of the Western tradition and in the process remade the domestic world of the British middle-classes.

Beauty has as many meanings as man has moods. Beauty is the symbol of symbols. Beauty reveals everything, because it expresses nothing. When it shows itself, it shows us the whole fiery-coloured world.

These new Aesthetic artists included romantic bohemians such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones; maverick figures such as James McNeill Whistler, then fresh from Paris and full of 'dangerous' French ideas about modern painting; avant-garde architects and designers such as E.W. Godwin and Christopher Dresser; and the 'Olympians', the painters of grand classical subjects who belonged to the circle of Frederic Leighton and G.F. Watts.

From 1860 to 1900, the Aesthetic Movement initiated sweeping artistic and design changes and its modern concepts of middle-class lifestyle and domestic environment reverberate even into our own time. Today Aestheticism is acknowledged for its revolutionary renegotiation of the relationships between the artist and society, between art and ethics, and between the fine and decorative arts, all of which prepared the way for the art movements of the 20th century.

The 1850s: the avant-garde takes shape

Individual Aesthetic artists drew inspiration from a variety of cultures and periods. They found beauty in Renaissance painting, ancient Greek sculpture and East Asian art and design, especially Japanese prints. This rich eclecticism is one of the Aesthetic Movement's most intriguing characteristics, one which Whistler and others exploited to stimulate new reactions to their works of art.

Despite using titles that might seem to establish a literary or historical connection, Aesthetic painters were only interested in evoking a mood or prompting vague associations. This unnerved a public who weren't used to this new way of 'reading' a painting. Aesthetic artists were also interested in employing the technique of synaesthesia in their paintings – the stimulation of one sense through another, such as imagery activating a sense of smell – in order to produce a layering of responses to the artwork and deepen the viewer's experience.

Architecture and decoration

If you want a golden rule that will fit everybody, this is it: have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.

A few key members of Rossetti's circle took a keen interest in the design arts, seeking to transform banal and pretentious furnishings and domestic objects of the middle-class home. With a refined sensibility to line and geometrical form or, in the case of William Morris, with a feeling for natural ornament and harmonious colour, these designers aimed to produce chairs and tables worthy of the name 'Art Furniture' and to create ceramics, textiles, and wallpapers entirely unlike ordinary 'trade' wares. These were to be quality household goods that would please the eye of the artist and grace the houses of Aesthetic patrons, collectors and connoisseurs. It was argued that if furnishings were refined enough in form, materials and their quality of making, and carefully considered in colour, they – and the decorative arts in general – could rise to a new level and blur the Royal Academy's longstanding strict division between the 'fine' arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture and so-called artisan crafts – decorative arts design and fabrication.

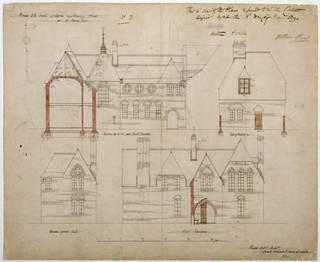

A perfect example of this approach can be seen in William Morris's Red House, designed by architect Philip Webb and described by Rossetti as 'more a poem than a house'. Its coordinated style, described as 'neo-vernacular mellowness with high art seriousness', would become Morris's trademark.

Morris enlisted the help of his wife, Pre-Raphaelite muse, Jane Burden and friends to furnish Red House, believing "the growth of decorative art in this country... has now reached a point at which it seems desirable that artists of reputation should devote their time to it". Morris established a widely influential commercial enterprise focused on the home as a centre of simple comfort and beauty, with designs based on simplicity of form, quality workmanship and truth to materials.

In the following years, artists' houses and their extravagant lifestyles became the object of public fascination. The influence of the 'Palaces of Art' created by Rossetti, Burne-Jones, Morris, Leighton and the Dutch painter Alma Tadema was out of all proportion compared to the numbers of people who ever actually gained access and saw these spaces for themselves. However, there existed at the time many books, illustrated articles and instructive manuals that supplied the necessary details.

The ideal of 'The House Beautiful' sparked a revolution in building and interior decoration and led ultimately to a more widespread recognition of the necessity of beauty in everyday life. This idea would have a lasting impact not only on architecture but also on social theory and political thinking for years to come.

Beauty in the home: furnishing the artistic interior

I have found that all ugly things are made by those who strive to make something beautiful, and that all beautiful things are made by those who strive to make something useful.

The Aesthetes' eccentric lifestyles piqued public fascination, fuelling a vogue for all things 'Artistic', whether this was an expensive redesign by a fashionable architect or the acquisition of a single Japanese fan for the mantelpiece. Manufacturers and new commercial ventures responded to the demand, making distinctive items available at various price points, attractive to even a modest budget. The middle-class home became the Aesthetic focus and an avalanche of 'How To' publications offered guidance on how to achieve the new look.

The flamboyant author and self-appointed style guru Oscar Wilde had much to say about creating 'The House Beautiful'. He covered each aspect of domestic decoration and gave some common sense advice. For example, "stained glass can reduce the glare from a large window and fill a room with more subtle lighting".

The artful home showcased an array of artistic bric-a-brac, but items of Japanese origin or inspiration took pride of place. Japan's forced opening to foreign trade in 1853 revitalised the European veneration of all things Japanese, exemplified by England's passion for old 'Blue-and-White' Asian ceramics. Extensive displays at the Old Water Colour Society and the 1862 International Exhibition's Japanese Court introduced a wider audience to enticingly 'exotic' Japanese forms. A Japanese inflection – featuring asymmetry, flat patterning, simplified form and elegant surface ornament – became a hallmark of the Aesthetic vocabulary.

Furniture forms were also reimagined by Aesthetic designers. Unlike the heavily ornamented curvilinear Louis XIV styles so popular with Victorian consumers, Artistic furniture is elegant and simple in design. Despite appearing 'modern' to today's eye, Aesthetic designs reference Asian, Egyptian, Greek, vernacular, and even delicate 18-century English examples.

Preferred furniture types – sideboards, corner and hanging cupboards, and overmantels – created the display platform for treasured items, including the ever-present blue-and-white china. Manufacturing and commercial establishments launched their own 'Art' lines, engaging versatile celebrity designers, including Godwin, Dresser, Walter Crane, and Lewis Foreman Day to produce designs for all types of furnishings.

Parody and decadence

The figure of the Aesthete, whose super-subtle sensibility and passionate response to works of art, emerged fully fledged in the 1870s. Considered to be tainted by unhealthy and possibly dangerous foreign ideas, the Aesthete was treated with a considerable degree of suspicion by journalists and the general public. However, by the beginning of the 1880s the Aesthete, with his self-proclaiming attachment to poetry, pictures and to the nuances of interior decoration – in short, the character so astutely adopted by Oscar Wilde – had become the popular butt of friendly satire. In both George Du Maurier's long-running series of sharply observed cartoons in Punch Magazine (which had begun as early as 1876) and in Gilbert and Sullivans popular opera Patience (1881) the velvet-clad Aesthetes were ridiculed for their 'stained-glass attitudes', overly precious speech, and enthusiasm for the curious appeal of pale lilies, sunflowers, peacock feathers, fragile blue-and-white china and Japanese fans.

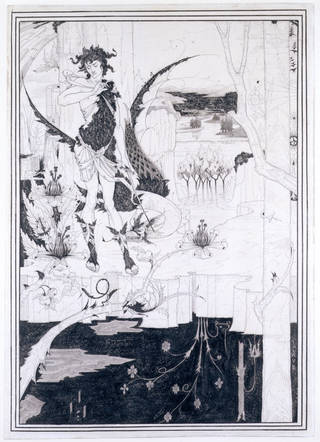

From the first, Aestheticism had critics suspicious of the lifestyle of its artists and the amorality of its imagery. By the 1890s, a new and dangerous French inflection had started to influence the British Aesthetic, including the self-indulgent and self-destructive ideas of the French writers Paul Verlaine, Stéphane Mallarmé, Arthur Rimbaud and Joris-Karl Huysmans. Criticism intensified following the brief career of the English illustrator and author Aubrey Beardsley with his drawings in black ink, which emphasised the grotesque, the decadent, and the erotic.

The Aesthetic project finally ended following the scandal of the trial, conviction and imprisonment of Oscar Wilde for homosexuality in 1895, following its outlaw that same year. The fall of Wilde effectively discredited the Aesthetic Movement with the general public, though many of its ideas and styles remained popular into the 20th century.