The warm colour and translucency of amber makes it a beautiful material to work with. Used by artists for centuries to create jewellery, ornate furniture, or to carve small figures, the origin of the material was once a mystery and many wild theories emerged, including that it was formed from the hardened tears of a young maiden, whale’s sperm, or even solidified lynx urine! It was only in 1757 that the Russian polymath, scientist and writer Mikhail Lomonosov demonstrated what amber really was – fossilised tree resin. In Europe, amber is primarily found in and around the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe.

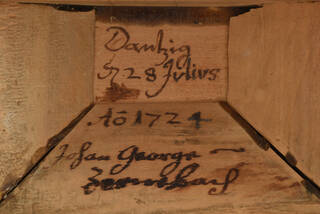

A fascinating discovery was made few years ago when a hidden inscription was found inside a cabinet almost identical to the V&A's. That cabinet is now part of the Museum of Amber collection in Gdańsk, Poland. Translated to English, the inscription read 'Danzig, 28 July 1724. Johann Georg Zernebach'. Although the cabinet in Gdańsk is decorated with ivory on the doors and on the top, the similarities between the two cabinets are striking. There is no doubt that both were made by the same workshop at around the same time. Still little is known about the maker, Zernebach, a master amber craftsman registered in the Guild of Amber, active in Gdańsk (formerly known as Danzig), in the 1720s.

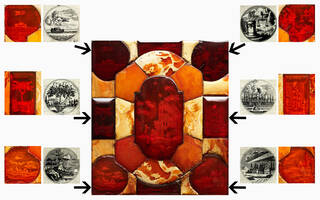

Many of the amber panels on our cabinet are exquisitely incised with figurative scenes, originally forming a significant part of the decorative scheme. The engraving was done on the back of each amber panel, and then plated with thin metal leaf before being glued to the wooden carcass of the cabinet. The metal leaf would originally have reflected the light, shimmering through the translucent amber to reveal the remarkable intricacy of the engraved scenes. Over time, the amber has naturally aged, forming tiny cracks that have obscured the engravings.

During the painstaking conservation treatment, Adriana Francescutto Miró, former Senior Sculpture Conservator at the V&A, was able to bring the designs on our cabinet back to life, revealing detailed allegorical scenes, emblems, landscapes and seascapes.

The front doors are decorated with large oval panels engraved with landscapes. Smaller corner panels each contain emblematic scenes with sayings in Latin.

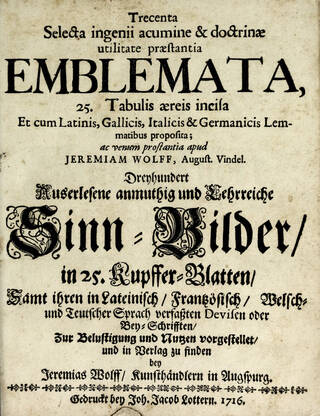

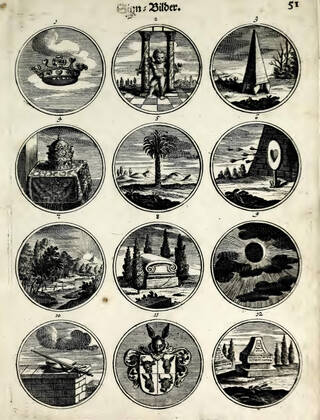

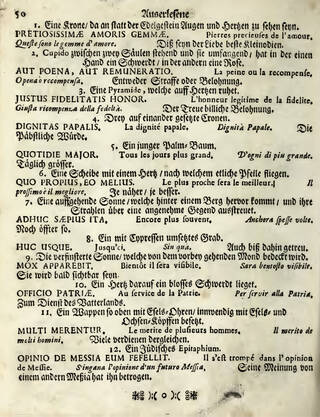

After conducting some research Kira d’Alburquerque, Senior Curator of Sculpture, found the source of these scenes in a book by Jeremias Wolff, published in Augsburg in 1714 and entitled Trecenta Selecta ingenii acumine & doctrinae utilitate praestantia Emblemata, which translates as Three hundred selected emblems, distinguished by their sharpness of wit and usefulness of doctrine.

The book contains emblems illustrated on 25 copper plates, accompanied by descriptions and mottos in Latin, French, Italian and German, on the opposite page. Although not clearly identifiable, many of the emblems relate to the theme of love.

Sadly, we don’t know anything about the person who commissioned the cabinet. A cabinet of this type would have been very costly and taken months to produce. The selection of emblems and the small sculpture at the top depicting Venus reclining with Cupid might suggest that the cabinet was made as a wedding gift. It could also have been a diplomatic gift. The two sets of five small drawers on both sides would have stored small collectable items, such as medals, jewellery, and gaming counters.

During conservation, the cabinet revealed one final secret – when it was x-rayed, we discovered that the entire lower part of the cabinet was, in fact, a hidden drawer, probably meant to safely store the most precious objects. Unfortunately, due to warping in the wooden structure, the drawer cannot be opened – maybe there are more secrets yet to be revealed...