The history of plywood is a history of the modern world. Combining lightness, strength and flexibility, plywood's story is a fascinating account of social, technological and design change over the past 170 years. Take a journey, through ten-ish plywood objects, from a leg splint to the fastest aeroplane of the Second World War, from the Antarctic to the Finnish forests, from the handmade to the digitally cut.

Plywood is made by gluing together thin sheets of wood called veneers, with the grain of each sheet running in an alternate direction. This creates a material that is stronger and more flexible than solid wood. The technique has been around for a long time – as early as 2600 BC in ancient Egypt – but it was not until the 1850s that plywood started to be used on an industrial scale.

Belter chair, about 1860

It has always been assumed that the history of plywood was mainly that of the flat board. This is not the case. Between 1850 and 1890 moulded plywood was the most common form of the material and furniture design the driver of innovation in its use.

The back of this chair, manufactured in around 1860, is surprisingly made of moulded plywood. It was made according to a technique for moulding furniture that was patented in New York in 1858 by John Henry Belter. His technique greatly increased the speed of manufacture and reduced production costs as chair backs could be made in batches of eight using a single mould.

Elevated plywood railway, 1867

During the 1800s designers and engineers were exploring ways to deal with increasingly crowded and chaotic city streets. In 1863 London opened the world's first underground railway, an incredible feat of engineering but with several fundamental flaws – it was very expensive to build underground and the air quality in the tunnels was poor. However, it was very successful for reducing congestion and other cities soon began to experiment with railways that moved traffic off the streets.

In 1867 a 107-foot long prototype elevated railway, made entirely as a moulded plywood tube, was exhibited at the American Institute Fair in New York. Seventy-five thousand people rode this extraordinary train, which was propelled by large fans. The designer, Alfred E. Beach, planned for the railway to be installed across the city, raised above the streets either on columnar supports or attached to the sides of buildings. Plywood's strength and lightness made it a good and cheap alternative to an underground railway of cast iron.

Cover and binding for Aurora Australis, 1908

It was not until the 1880s that plywood boards began to be made on a large scale. The Russian company A. M. Luther manufactured them in huge quantities and their most successful board products were tea chests and packing cases.

These plywood packing cases gained special notoriety from their use in Ernest Shackleton's 1907 – 09 Antarctic expedition. The expedition required over 2500 cases to carry provisions and equipment. Plywood was chosen for its lightness and strength. The cases were able to withstand extreme Antarctic conditions, including being buried beneath ice during blizzards. They were reused by the crew to make furniture for their living quarters and as covers and binding for Aurora Australis – the first book to be written, illustrated, printed, published and bound in the Antarctic. Astonishingly, Shackleton and his crew took a printing press on their expedition to 'guard [them] from the danger of lack of occupation during the polar night'.

Haskell canoe, 1917

Canoes like this were manufactured by the US firm Haskell (later Haskelite) from 1917 and sold in large numbers. They were made by moulding a single piece of plywood using a water-resistant glue that was developed by the company. The canoes were incredibly light, weighing under 27 kg (60 lbs), and very strong.

The company's advertising campaign focussed on the canoe's strength and durability. Advertisements showed the canoe supporting "seven grown men, a six-foot length of 12x12 inch solid oak timber, a hull full to the gunwale of damp sand [1551 kg/3420 lbs in total]", or surviving being thrown from the second-storey window of the Haskell factory.

The Haskell company later used their experience with moulding and water-resistant glues in the manufacture of plywood aircraft and vehicles.

Paimio armchair, 1932

From the 1920s, modernist architects and designers began to exploit and celebrate plywood's ability to be shaped into curved forms. Plywood was of particular interest as it was considered an industrial material – it was well suited to mass manufacture and its factory production symbolised the new machine age.

This chair was designed by the Finnish architect Alvar Aalto for the Paimio Tuberculosis Sanitorium in Finland and made in a small factory. The thin, light and curved plywood seat is suspended between two narrow frames, giving the impression of a seat floating on air.

In 1933 the same factory began manufacturing the chairs for general sale, alongside other furniture designs by Aalto. His furniture was exported in large quantities to the UK and the USA, where its innovative use of plywood had a significant impact on other designers.

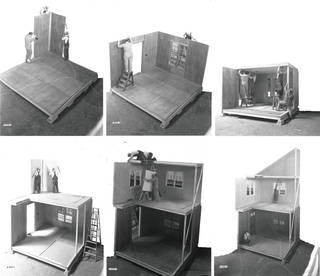

Forest Products Laboratory (FPL) house, 1937

In the United States schemes to create cheap, factory-produced houses flourished during the 1930s. This was motivated by high unemployment, small household incomes and a shortage of low cost housing during the Great Depression. Designs for prefabricated houses focused on quick fabrication and easy disassembly. Plywood was perfectly suited to standardised, lightweight panel systems which could be factory-produced and assembled on site. The invention of synthetic glues in the mid-1930s also meant that plywood manufacturers could produce new waterproof plywoods, ideal for exterior use.

During the Depression the US Forest Products Laboratory (FPL) published schemes for an experimental 'all-wood' house that could be factory-produced using standard plywood panels, then quickly erected on site. In 1936 they built a demonstration house at the Madison Home Show. Twelve thousand visitors queued to see the fully furnished house. They marvelled at the fact that the parts were made in a factory and the house could be built by seven men in only 21 hours.

DKW car, 1938

Throughout the 20th century designers and engineers experimented with plywood as a material for vehicle construction. Often stronger, lighter and more elastic than metal, plywood was used flat and also moulded for the bodies of cars, sidecars and vans. Plywood's use in cars was often influenced by aeroplane and boat design and a number of companies worked across several of these fields. The French entrepreneur Georges Lévy, for example, designed both plywood sidecars and seaplanes – the floats on the seaplanes essentially re-using the rounded form of the sidecar's body.

From 1928, the German company DKW used moulded and flat plywood for the body of their affordable family cars. Combatting prejudice that plywood was less reliable than metal, DKW emphasised its unique properties – strong and stress-bearing, easy to repair and quieter on the road due to better suspension. DKW's advertisements demonstrated plywood's strength and modern, industrial credentials by showing photographs of factory workers standing on a plywood board, balanced on the roof of one of their cars.

Mosquito aeroplane, 1941

Plywood's most technologically significant use from the 1910s to 1945 was as a material for aeroplane design. Its strength and lightness allowed for the construction of radical new planes that revolutionised the nature of flight. In the early 1910s, ground-breaking experiments with moulded plywood allowed for the construction of the first enclosed, streamlined aeroplane fuselages. These moulded plywood shells – known as 'monocoque' – were strong enough to be self-supporting, meaning that the planes did not need significant internal structure or cross-bracing. The revolutionary 'monocoque' fuselage became standard in future aeroplane design.

The British de Havilland Mosquito (DH-98) was the fastest, highest-flying aeroplane of the Second World War. Its moulded plywood monocoque fuselage made it light and quick enough to fly without defensive weaponry. The Air Ministry initially wanted to commission a metal plane. De Havilland convinced them to trial the Mosquito as a low-cost design that could be made relatively cheaply using workers from furniture and other wood working factories in Britain, Australia and Canada.

Charles and Ray Eames designs, 1940s

American designers Charles and Ray Eames experimented with plywood during the Second World War, developing a method for moulding complex curved forms. In 1942 they designed a lightweight, stackable moulded plywood leg splint for the US Navy. Later in the war they went on to make plywood parts for aircraft.

The Eames's design for the DCM (dining chair metal) with its three-dimensionally moulded seat was greatly influenced by their wartime work. It was one of the most influential chairs of the second half of the 20th century and was imitated and adapted by designers around the world. British designer Robin Day said of the period: "Every designer I knew had a picture of the Eames chair [the DCM] pinned to their drawing board".

Mirror dinghy, 1960s

The 1950s and '60s saw an explosion of do-it-yourself. Plywood was particularly suitable for working at home. Easy to shape, it did not require complicated tools, was forgiving of amateur workmanship and was easily integrated into post-war leisure culture.

The Mirror dinghy, made mainly of marine plywood, was and remains one of the most popular boats of the 20th and 21st centuries. Sold as a kit of parts for home assembly, it was intended to be affordable and was aimed at a wide market of beginner sailors. The dinghy used a construction method advertised as 'Stitch and Glue' in which plywood panels were joined by loops of copper wire threaded through drilled holes. This allowed for very easy construction by amateurs with no experience of woodworking.

Opendesk, 2013

Plywood is one of the most common materials of the digital age. Makers and designers share plywood projects around the world, either by distributing digital cutting files for CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machines, or with videos and images posted online.

The company Opendesk holds no stock and operates entirely online. Under a system of distributed manufacturing their designs can be downloaded anywhere in the world for cutting on a CNC router – a computer controlled machine that cuts with a rotating bit called an endmill. Individuals can make the furniture themselves, or be put in touch with a local maker. Virtually all Opendesk designs are plywood. The material was chosen after balancing cost, availability and global standardisation, to ensure uniform construction.