Embroidery Pattern Books 1523 - 1700

For wealthy women of the 16th and 17th centuries, embroidery was an important part of everyday life. Clothes, household furnishings and book covers were all embroidered and the more lavish and extravagant the design the better. In some families where the women were unable or unwilling to do the work themselves, professional embroiderers could be employed, but for a lot of women embroidery provided a fulfilling and creative occupation.Although many women were skilled embroiderers, rather fewer could design the intricate, detailed patterns that were fashionable. This problem was overcome in several different ways. Pattern draughtsmen could be commissioned to create a design to order, drawing tutors employed or, by the 17th century, fabric with the pattern already drawn out could be purchased.

By far the most commonway of getting a design however, was through pattern books. The first recorded example was published by Johann Schonsperger in Germany in 1523 and others followed quickly throughout Europe, especially in France and Italy. Between 1523–1700 more than 150 separate titles were published. Although the high number of titles would seem to indicate a wide range of different patterns, plagiarism was rife and the same designs appear right across Europe over and over again; sometimespublishers would have new wood blocks cut with small embellishments but quite often they were a direct copy. In Britain, the output of pattern books was small and only four titles have been recorded. This was partly due to the paucity of good engravers but also publishing laws which meant only certain types of books could be published in quantities large enough to be financially viable.

Most pattern books included sections on lace and cutwork as well as embroidery and were small enough to be easily handled. The patterns were mainly floral or geometric, suitable for repeating as borders, but sometimes whole scenes were drawn out.

Transferring a pattern from a book to material was done by ‘pouncing’: this was a technique which involved pricking out the outline of the pattern with a pin, attaching the page to a piece of fabric then rubbing soot or charcoal through the pin holes so that when the page was removed the pigment would be left in place. Many patterns were printed on squared paper. This allowed the embroiderer to increase the size of the finished embroidery by drawing out the designs using the same proportions but on a grander scale onto more squared paper, often provided by the publisher. Experienced or confident needlewomen would use the paper to adapt the designs for specific projects or for their own work. As women got more skilled they could move from embroidery books to patterns designed for bookbinders or calligraphers and for the really inventive, herbals and emblem books.

For modern embroiderers these little books still provide a source of inspiration, and for historians a fascinating insight into 16th century publishing and domestic history.

La Vera Perfettione del Disegno, Giovanni Ostaus

La Vera Perfettione del Disegno

Giovanni Ostaus

Venetia

1591

Pressmark 95.0.39Most pattern books included sections on lace and cutwork as well as embroidery and were small enough to be easily handled. The patterns were mainly floral or geometric, suitable for repeating as borders, but sometimes whole scenes were drawn out, such as the one shown here.

Model-Buch Dritter Thiel, Rosina Fuerst

Model-Buch Dritter Thiel

Rosina Fuerst

Nurnberg

1676

Pressmark 95.O.16An embroidery design with pinholes caused by 'pouncing'.

Pouncing was a technique which involved pricking out the outline of the pattern with a pin, attaching the page to a piece of fabric, then rubbing soot or charcoal through the pin holes so that when the page was removed, the pigment would be left in place.

Embroidery design from Das Neue Modelbuch, 1593

Embroidery design from Das Neue Modelbuch

1593

St. Gallen

Pressmark 95.O. Box 1This embroidery design was to be transferred by pouncing.

Pouncing was a technique which involved pricking out the outline of the pattern with a pin, attaching the page to a piece of fabric, then rubbing soot or charcoal through the pin holes so that when the page was removed, the pigment would be left in place.

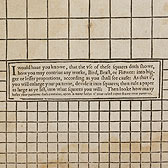

Squared paper from A Schole-House for the Needle, Richard Shorleyker

Squared paper from A Schole-House for the Needle

Richard Shorleyker

London

1623

Pressmark 95.O.50Squared paper, such as this from A Schole-House for the Needle, was provided to scale up embroidery drawings from the book.

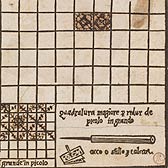

Embroidery design on squared paper from Il Monte, libro secondo

Embroidery design on squared paper

Il Monte, Libro Secondo

Giovanni Bindoni

Venetia

1559

Pressmark 95.O.38An example of an embroidery design created on squared paper.

Symbolorum & Emblematum, Joachim Camerarius

Symbolorum & Emblematum

Joachim Camerarius

Nuremberg

1593-1604

Pressmark CLE.C.13As women got more skilled at embroidery they could move from using patterns from embroidery books to patterns designed for bookbinders or calligraphers and, for the really inventive, herbals and emblem books such as this.

The National Art Library of the V&A holds 60 original embroidery books including the only extant copy of Richard Shorleyker’s‘Schole house for the needle’ of 1632.

A copy of Arthur Lotz’s ‘Bibliographie der Modelbucher’ (1963) annotated with NAL pressmarks can be found in the National Art Library at REF 746.2016 LOT.

In 1933, Arthur Lotz compiled a bibliography of all known needlework pattern books and allocated a number to each title. The Lotz number has become the standard international language for pattern books and is often cited in other reference works.

V&A Innovative Leadership Programme

The V&A Innovative Leadership Programme is aimed at managers working in the arts & creative industries looking to develop new skills, insight and opportunity. Applications are now open for the next course.

Apply now