Opera developed in western Europe in the early 17th century as a means of bringing together all the arts, including painting, poetry, drama, dance and music. Our collections document its evolution from early Baroque extravaganzas through to contemporary productions.

Opera's early origins

Initially enjoyed in the Italian and French royal palaces in the 17th century, opera emerged from spectacular, expensive productions intended to impress visiting dignitaries and present a positive image of a ruler and his court. They included vast processions, dances, sung episodes, sumptuous costumes, and acted interludes, accompanied by coaches, chariots and elaborate stage effects. The stories or themes were taken from classical mythology, often drawing parallels between the present day rulers and mythological gods or heroes.

The first recognisable opera, with the story told through song and music, was Orfeo by Monteverdi, first performed in Mantua in Italy in 1607. In our collections is a review for its first London production, which took place more than 300 years after it was written. Although Orfeo, based on the Greek myth of Orpheus, remains the earliest opera still regularly performed today, it was not heard outside Italy until the 20th century.

18th-century opera

The 18th century saw an explosion of opera across Europe. Opera houses were built in all the major European cities and new operas were commissioned for each season. In London, the King's Theatre, Haymarket, offered opera as the main evening's entertainment, usually interspersed with dances and sometimes a short play or farce as an afterpiece. Operas were composed for individual singers, who were the great stars of the performance. The composer's job was to write music, often within a short space of time, to show off the star's voice. Star singers had considerable freedom to improvise. Certain passages of musical ornamentation were left to the singer's own inclination and would change from night to night.

Two opera forms developed: 'opera seria' (serious opera) and 'opera buffa' (comic opera). In opera seria, the story was told in recitatives (sung in the natural rhythm of speech), while sung arias (long accompanied songs for a solo voice) expressed emotion. The characters were noble or mythological and the plots were about political intrigue and history. The German composer, George Frideric Handel, who had settled in London with his patron, George I, introduced opera seria to the city. His operas were vocally elaborate, with long arias designed to display the virtuosity of the singers.

The libretto (manuscript) for Radamisto, Handel's first opera for the newly formed Royal Academy of Music, was used as a prompt book for the opera's first performance on 27 April, 1720, at the King's Theatre, London. Markings in the text note the performers' moves and calls, as well as cueing sound effects. The text is written in Italian on one side, with an English translation opposite. 18th century auditoriums would have been candlelit, allowing the audience to read the text during the performance.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Another 18th century champion of opera is Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Often considered one of the greatest composers of all time, Mozart, born in Salzburg, Austria, started writing music before he was four years old. As a child prodigy, he toured the courts of Europe playing his own compositions to adoring audiences. Once he grew up, his audiences lost interest and, despite his genius, he had to work hard throughout his life to earn a living, finding patrons and composing music to order. He died almost penniless.

Today, Mozart's operas are some of the best loved. He wrote several well-known opera buffas, such as The Marriage of Figaro and Don Giovanni. Compared to the pomp of opera seria, opera buffa staged ordinary characters and dealt with lighter topics. A playbill in our collections promotes an 1841 performance for Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro at Drury Lane, part of a three-month opera season given by a company gathered from theatres across Germany and Vienna.

19th-century nationalism and the rise of the composer

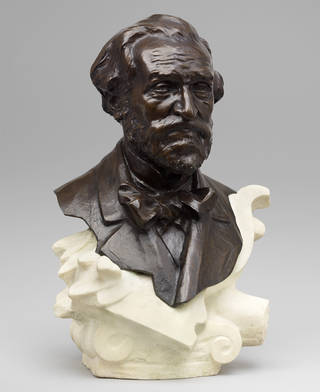

In the 19th century, the composer assumed more importance than ever before. This was the era of Richard Wagner and Giuseppi Verdi, who weren't just composers but national heroes. Nationalism became a driving force for many European countries and opera was now seen as a means to express identity, with Wagner in Germany, Verdi in Italy, Mussorgsky in Russia, and later, Janacek in Czechoslovakia. With this rise in nationalism, different operatic styles developed. In Russia and eastern Europe, composers became inspired by history and literature. In France, 'Grand Opéra' flourished, with great scenic effects, action and ballet. 'Opéra Comique', a genre of opera that contained spoken dialogue as well as sung arias, was also very popular. A well-known example is Carmen by Bizet.

In the second half of the century, Richard Wagner revolutionised opera with The Flying Dutchman (1843), Parsifal (1882) and the four operas of The Ring of the Nibelung (1869-1876). Wagner gathered music, drama, poetry and staging, in what he called 'music drama'. He frequently used the leitmotiv, a recurrent musical phrase associated with a character, event or idea, and aimed to compose works that abandoned the usual operatic conventions of recitative and aria, blending orchestra, voice and words into one dramatic unity.

In Italy, the voice remained predominant. The 'bel canto' (beautiful singing) tradition continued, championed by Giuseppe Verdi, who wrote a number of much-loved and passionate operas, such as Rigoletto (1851), La Traviata (1853), and Aïda, (1871).

20th-century individualism

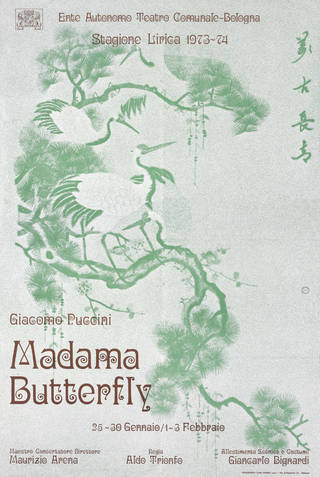

The 20th century saw a more individualistic approach. In Italy, Puccini recreated 19th century romanticism with well-loved operas such as Tosca (1900), Madam Butterfly (1904), and Turandot (1926). In France, Debussy explored poetic and evocative melody, composing Pelleas and Melisande, (1902), while in Germany, Strauss was dissonant and intentionally shocking in his approach, with extreme subject matter such as Salome, with its erotic 'Dance of the Seven Veils', in 1905. As the century progressed, the general trends of opera became even more fractured, under the influence of the Avant Garde movement. In Austria, Alban Berg wrote the atonal Wozzeck in 1925, while Kurt Weill created his jazz-inspired work, The Threepenny Opera, in 1928. In Britain, Benjamin Britten composed both 'traditional' operas like Peter Grimes (1945) and pared-back 'chamber operas' such as The Rape of Lucretia (1946) and The Turn of the Screw (1954).

As opera continues to evolve, it becomes more varied than ever. The great operas of history maintain their popularity through repeated reinterpretation, but are presented alongside earlier rediscovered works and new contemporary operas, such as Mark Anthony Turnage's Greek, based on Stephen Berkoff's original play, which sets the Oedipus myth in 1980s London. The art form remains as relevant and entertaining today as it was 400 years ago.