Architects have been drawing for a long time, often without much hope that their ideas will be realized. Some of the most famous images from the history of discipline, like the Cenotaph (or death monument) for the astronomer Newton designed by Étienne-Louis Boullée, would have been impossible to construct even if the budget had been forthcoming.

For many years, this use of drawings as a way of leaping into an imaginary future was sometimes mocked as “paper architecture” – great idea, but unbuildable. But as with many presumptions about architectural practice, postmodernism changed all that. This is one of the fascinating stories we have researched for our forthcoming V&A exhibition Postmodernism: Style and Subversion. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, a time of recession when few big commissions were available anyway, architects used drawings to explore their most outrageous and radical ideas: Archigram’s walking city, or Gaetano Pesce’s Church of Solitude, a cavernous underground cathedral proposed as a refuge below the skyscrapers of Manhattan.

A turning point came in 1979, when New York gallerist Max Protetch began showing architectural drawings – for both realized and unrealized projects. Figures like Michael Graves, who would become the most widely recognized exponent of postmodern style in America, had received only limited recognition until that time. But Graves’ beautiful drawings, halfway between cartoons and Beaux Arts renderings, were a big hit.

Protetch managed to create a market for these works on paper, and helped make Graves a star. As architects increasingly became celebrities in their own right, winning big urban commissions like the Denver Library (below, awarded to Graves in 1990), their drawings became ever more lavish and desirable – a good way to convince a client, as well as express an idea.

Of course, these renderings are made far into the design process, after many other preliminary sketches have been made. But they are still hand drawings, and therefore seem to capture the architect’s imagination in a direct and unmediated way. In more recent years, a new possibility has arisen which makes “paper architecture” even more potent and persuasive. This is the use of high-quality photography in relation to paper designs – in this case, three-dimensional models rather than drawings. Architects like Graham West, based in London, work with such accurate and beautifully crafted models that it can be difficult to tell if one is looking at a miniature study, or the real thing.

Of the two above images of a residence designed by West, only one is “real” – the other is a detail shot of the model he commissioned. (I’ll let you guess, answer below.) Though the motivation of this extreme hyper-realism isn’t that different from the one that animated Graves – to help the client imagine the architect’s aesthetic world before it exists – there is a surreal slippage here between different stages of reality, the prototype and the product. It’s a confusion that the German photographer Thomas Demand has famously exploited.

The above image, entitled Poll 2001, is enough to give anyone who remembers the Gore-Bush recount a shiver. Demand has duplicated the banal forms of desks and phones in paper – or perhaps I should say triplicated them, because of course the photo is an image of a copy. And there are even more levels of reality at work: Demand based his mockup on a printed newspaper image, so in fact his “paper architecture” serves as a mediator between one photo and another. In another work, entitled Treppenhaus, Demand drew not on an image but rather his own memory to create a full-scale model of a stairway from his own secondary school.

You can hear him talking about this work here. He left out every detail he couldn’t remember, and the eerie quality of the photo results to some extent from this stripping-away of reality. Mike Kelley’s similar work Educational Complex (made in 1995, the same year as Demand’s staircase) is another retrospective view, an architectural model in reverse. In this case the building is a composite of ever art school Kelley had ever attended; like Demand he simply left out anything he couldn’t remember.

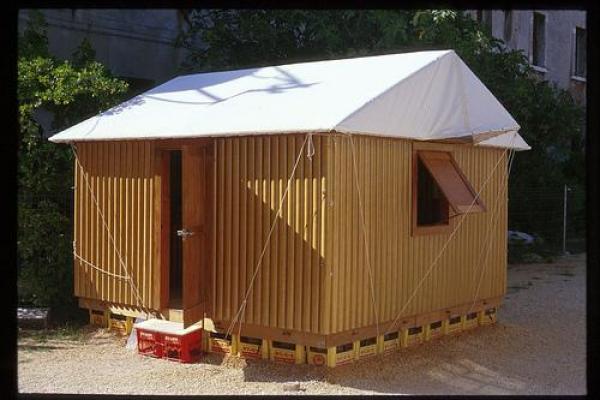

One final example of paper architecture shows how the aesthetic of the model can, occasionally, be turned to the task of a practical building. Or at least a semi-practical one: below are two images of Shigeru Ban’s cardboard tea house, auctioned off to the highest bidder in 2008.

This project shares something of the condensed, unearthly quality of Demand’s photos, but in this case the simplicity and “poverty” of materials also refers to the tradition of humility in building Japanese tea houses. Of course, given the commercial nature of the project, Ban is using modelmaking techniques to extend even further the marketing of architecture that Protetch began three decades earlier. But to be fair, he first explored the techniques of paper architecture while helping to conceive emergency housing after the Kobe earthquake, a project he has revived in the wake of the recent tsunami disaster. So “paper architecture” can be completely pragmatic after all.

My thanks to Graham West for his suggestions for this post. In the pair of shots of his work, the image on the left is a model and the one on the right the finished residence.

Awesome post! i love the Russian Paper Archietcts and this put them in a really interesting context

Thank you