While many people are aware of the use of whales’ baleen in historical fashion, the use of ambergris in the perfume industry is less well known. Volunteer Lydia discusses the origins and use of ambergris in fashion and the effect on whale populations.

Written by Lydia Caston, Volunteer

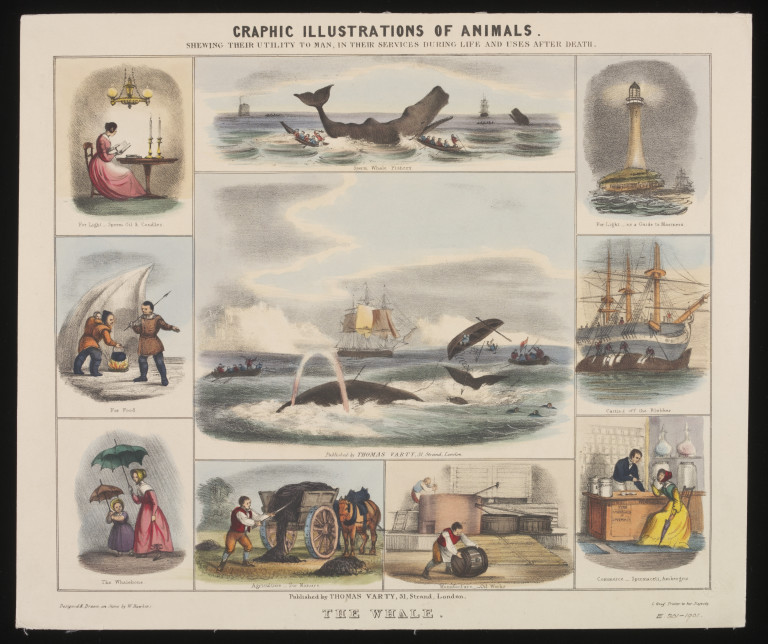

Large-scale whaling began around 1880. This coincided with the expansion of the fashion industry, the rise of the department store and greater disposable income for many families. Whalebone, the colloquial name for baleen, acts as a strainer for filter feeder whales that eat small plankton and krill. As baleen plates are made of keratinous protein like our hair and finger nails, they are strong and pliable. In 18th and 19th century fashion, baleen was used to stiffen and shape women’s garments such as petticoats, corsets and bodices, and was used as one of the main resources for umbrellas until the late 19th to early 20th century. The high demand for baleen led to overhunting and significantly reduced whale populations.

One of the most fascinating objects Richard showed us was a piece of ambergris. Ambergris was widely employed by European and American perfumers. So popular was ambergris in the 19th century that the 1851 novel Moby Dick suggested that ‘a faint stream of perfume’ came from the corpse of a whale. Resembling a large solid rock, ambergris was used as a fixative in the perfume industry and whales were targeted in the hope that ambergris could be extracted.

Ambergris is developed in the intestines of whales. Sperm whales eat a large amount of squid and cuttlefish, but cannot digest the beaks and pens. To ensure that the indigestible parts do not damage the mamma’s organs, they are covered in a greasy substance. This is ambergris, which remains inside the whale for the rest of its life. If expelled, it can fatally rupture the whale’s rectum. As ambergris remains in the sea after its release from the whale, a white coating forms around it due to oxidisation in the salty water. Typically, the lighter the colour of the ambergris, the sweeter the fragrance.

Ambergris was integrated into cigarettes, was used as incense, flavoured food and was thought to prevent infection with the plague. Perfume became an important way to mark status for men and women in 19th-century Europe. Whilst some scents were home-made from collected flowers, herbs and spices, cities offered ready-made concoctions which favoured floral and ambergris scents. Throughout her reign, Queen Victoria wore Fleurs de Bulgarie. Combining notes of Bulgarian rose, bergamot, musk and ambergris, it continues to be sold today with its original ingredients.

Ambergris’ status as a waste product means that it is not covered by animal protection provisions and its use remains legal in the United Kingdom, France, Switzerland and New Zealand. It is not the only animal resource used in the perfume industry. Civet is extracted from the anal glands of the civet cat, castoreum comes from the beavers’ sacs, and musk from the sheath of the musk deer. From Dior’s Miss Dior, Rochas’ Femme, Guerlain’s Shalimar to fragrances by Chanel, Givenchy and Gucci, ambergris plays an important role in some of the most familiar perfumes today. Synthetic chemical alternatives to ambergris do exist, but are rarely used in luxury perfume brands. Their increased use could safeguard the future of whale populations.

In the next blog post, students from the London College of Fashion explain the idea behind their audiovisuals in Fashioned from Nature.