by Lupt Utama, MA candidate, V&A/RCA History of Design

I grew up in the mountainous city of Chiang Mai, in northern Thailand where Myanmar and Laos meet. As a young boy, I vividly remember my grandmother’s elaborate cotton pha-sin – a tubular skirt which she secured with a chainmail silver belt, to be traditionally worn with a hand-dyed cotton blouse with three-quarter-length sleeves.

I was particularly intrigued by the tapestry patterns at the bottom of these pha-sin: some were faded as the fabrics were naturally dyed, and each was named. One was called ‘Running Water’ or Lai Nam Lai. It represented the flowing water in the river and reminded me of a stormy river with sinking boats in the middle of it.

My mind fixated on those complicated patterns and how these skirts were woven and given a name, and on the clever women who could create and weave fabrics from their own imagination. I started to create my own stories based upon different patterns on my grandmother tubular skirts: stories of bears and tigers, of men and angels, and lightning and rivers.

***

These childhood experiences subsequently developed into a love of Thai textiles, artefacts and history and, in particular, an academic interest in court textiles and dress in 19th-century Thailand and Myanmar. Here as elsewhere, clothing and dress were redolent with shifting power relationships. More specifically, the hybridised dress styles of the indigenous peoples and European colonialists have acted as a key narrative in thinking about the formation of modern identity in Southeast Asia.

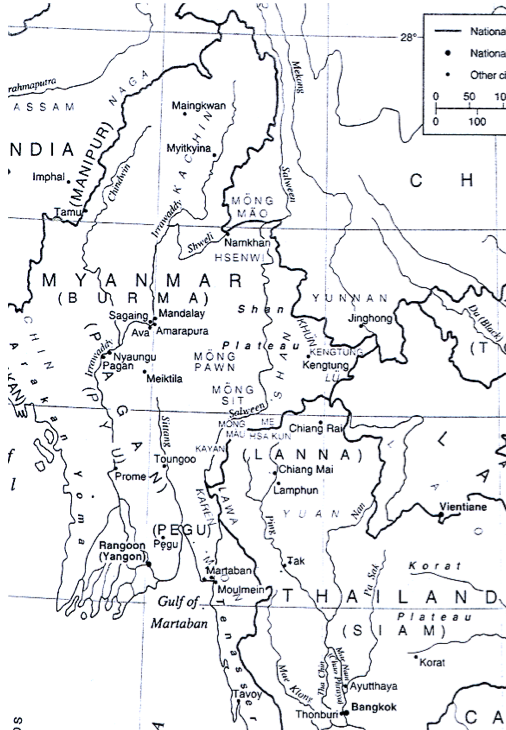

A recent talk by Dr Susan Conway (Research Associate, SOAS) provided a compelling backstory. This paper, ‘Power Dressing: Siam, Burma, China and the Tai’, addressed the politics of dress in Southeast Asia by exploring the configuration of ‘superpowers’ in the region before the arrival of European colonialism during the 19th century. To do so, it teased out the relationships and relative political agencies between the three regional ‘superpowers’, Siam (modern-day Thailand), Burma (modern-day Myanmar) and China, and the smaller principalities or city states in the Shan States (now part of Myanmar) and Lanna (Northern Thailand). (illustration 2)

The discussion was framed explicitly in relation to material embodiments of power, with Conway using ‘power’ in two ways: on the one hand to denote the mystical authority of Theravada Buddhist kingship, and on the other as a political force, expressed through tributary relationships and marital alliances. The tributes given by each principality were defined by available natural resources, and included silver, gold, timber, cotton, deer horns and ivory, but the main contribution expected was manpower, particularly during times of war.

Conway showed how the tribute system spread through all levels of society, so that even smaller, outlying communities presented a local ruler with a token of their respect annually; in this instance the material tribute could be as simple as wild orchids. In return, those giving tribute received acknowledgment in material form, including inscribed seals and gifts, such as dress, regalia and textiles. This was not gift giving amongst equals but a carefully calibrated series of exchanges that articulated the asymmetry in the power relationships between the superpowers and smaller principalities.

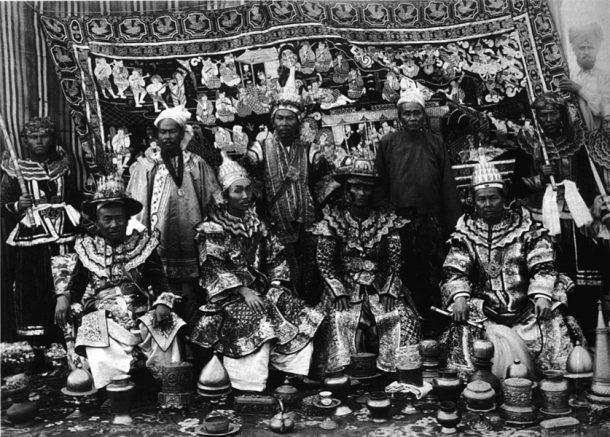

The idea of ‘tribute apparel’ was related by Conway to what would seem to be a very modern notion – ‘power dressing’. Turning the concept on its head – here after all were people dressing to reflect their comparative lack of power – she showed how the court dresses, textiles and regalia given to principalities by regional superpowers resonated with power and respect. Most notably, wearing these garments was a requirement when paying tribute to the courts of Siam, Burma and China. A photograph taken at the Delhi Durbar in 1903 (illustration 1), an event organised by the British Colonial Office in Delhi, clearly shows the rich variety of styles and values of tributary dress.

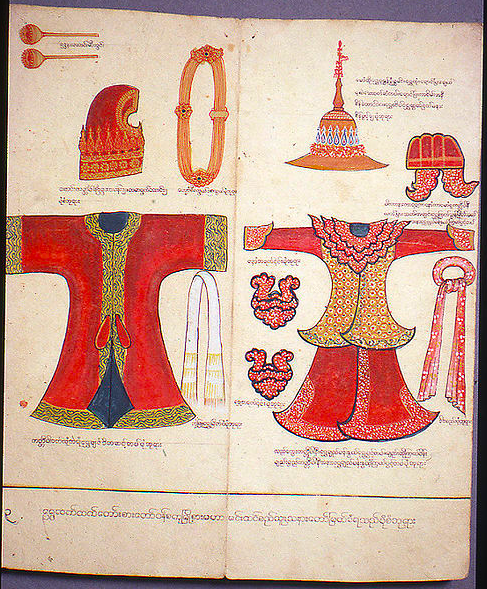

Although beyond the scope of the paper, it is worth noting that the tribute system was of considerable antiquity: the Shan princes paid tribute to China until the 16th century, when most of them came under the authority of Burma. The tribute systems in the Shan States were notably complex, as those Shan princes in the north states, closer to the border with China, continued to accept the authority of the Emperors of China through the office of the Governor of Yunnan. Dress played an important part in articulating these power relationships. The Imperial Court sent a ‘Chinese robe’, like the 19th-century example shown here (illustration 3), as part of a tribute dress to be worn (Illustration 4) during the tribute ceremony, itself a lavish affair, in order to reiterate the authority of the Chinese Emperors.

Similarly, Shan princes who paid tribute to Burma attended the Royal Court of Amarapura until 1823, when the court moved first to Ava and finally to Mandalay during the reign of King Mindon (r. 1853-1878). The Burmese court sent these princes beautiful and heavily embroidered tribute dresses of gold thread and sequins.

Photographs, such as the image showing the prince and mahadevi of Yawnghwe (illustration 5), document garments that placed considerable restrictions on the movement of wearers, providing a suggestive metaphor, perhaps, for the political constraints experienced by those under Burmese sovereignty.

Political anxieties around dress were evident, too, in the strict dress codes and sumptuary laws attached to court and tribute dresses. Folding manuscripts, comprising detailed drawings and sketches, carefully detailed the type of textiles, regalia and jewellery appropriate for court officials under the Burmese kings. (Illustration 6)

Lanna princes also paid material tributes – first to Burma until 1774, when the Burmese were expelled from Chiang Mai, then the capital city of Lanna Kingdom – and then to Siam. Tributes from the Lanna principalities to the Bangkok court took the form of trees made of gold and silver, their outstretched branches exemplifying the protection that would be extended to those who paid tributes, alongside ivory and teak timbers.

The Siamese court reciprocated with Indian silk brocades, jewellery and regalia. Its most customary gift was the seu-krui. As images (illustration 7) and surviving examples (illustration 8) show, this was a magnificent full-length coat of gold-thread embroidery, intended to be worn over court dress.

My own research further complicates this picture by showing that during the reign of King Chulalongkorn of Siam (r. 1868-1910), the newly introduced European-style diplomatic and military dress uniforms were imposed on the Lanna princes as a form of tribute. These new uniforms, as worn by the 7th King Ruler of Chang Mai and Ruler of Lanna in a late 19th-century painting, essentially ‘recast’ the Lanna princes as State Governors, instead of rulers in their own right, reflecting the increasingly centralised authority of Siam over the regional princes. (Illustration 9)

In combination, these examples clearly suggest how dress was employed as part of a political strategy during the pre-colonial period in Southeast Asia. As Conway’s presentation showed, clothing and textiles provide vital evidence in discussions of identity, loss and imbalances of power, regional geopolitics and the imagined borders between principalities. Engagement with the materiality of tribute apparel, as well as the customs associated with its gifting and use, reveals how the identity and agency of those who wore it were concealed and even suppressed. Conversely, at the same time, the exact same forms of dress enhanced the status and power of those to whom tribute was being paid – in this instance the regional superpowers of Siam, Burma and China – putting a very different spin on what is meant by ‘power dressing’.

The V&A/RCA History of Design Research Seminar series returns on Thursday 22 January 2015, when Professor David Matless (University of Nottingham) presents, ‘In the Nature of Landscape: Cultural Geography on the Norfolk Broads’. Further details of all seminars in the series can be found here.

Please join me on my new blog about Burmese silver, I need Burmese translations and Jataka narratives if you could help please

Hi John,

I’m replying on behalf of the author, Lupt Utama, who regrets to say that he is unable to read Burmese, but thanks you for your kind interest in his post.

Very best luck with your blog — it looks fascinating!

Elaine

Hi,

Nice collection and I am very interesting historical dresses.Btw I am from burma and also interesting in burma language

Regards

Thanks for your info. very much

No.5. is the picture of Yaunghwe Saopha Sir Sao Maung and his Mahadevi Sao Nang Yar.