In early March, the news and social media were full of photographs of queues of customers at supermarket checkouts, their trolleys filled with bales of super-saver, multi-ply bounty packs; then pictures of the long aisles with their white expanse of empty shelves. In Hong Kong, Singapore, Australia, Japan, US and UK, such images became the signifiers of imminent apocalypse, further driving panic-buying in an endless feedback loop. Fights broke out over the now precious commodity, and supermarket workers restocking the stripped-bare shelves had to protect themselves from the hordes with hastily constructed barricades. Stockpiling was criticized as an uncivil act, placing unnecessary pressure on supply chains, and customers were rationed to one pack each.

For about three weeks, as country after country entered into lockdown, and families prepared for self-isolation, our most private act became a matter of public anxiety and scrutiny. Much of the world prefers to use a jug of water for their ablutions – but, in a crisis, toilet paper, which contributes to massive deforestation, proved the basic necessity that our disposable culture felt it could not live without. The shortage was the subject of analysis by pundits and psychologists, and numerous jokes and memes. Two violinists wearing life jackets went viral with a video in which they played the theme tune to Titanic in front of supermarket shelves emptied of toilet tissue.

The Great #Toiletpapercrisis seemed worthy of an epilogue to Charles Mackay’s miscellany of folly, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (1841). Mackay’s study of ‘moral epidemics’ such as the South-Sea Bubble and ‘tulip mania’ sought to “show how easily the masses have been led astray, and how imitative and gregarious men are, even in their infatuations and crimes”. The recent frenzy, explained as an example of ‘herd mentality’, was not the first time toilet roll was the subject of collective, consumer panic. In 1973, at the height of the oil crisis, a throwaway remark by the TV comedian Johnny Carson warning of looming shortages caused a similar false scare. It was a self-fulfilling prophecy, with panic buying forcing prices up and leading to four months of scarcity.

Toilet paper, like Covid-19, originated in China. In 105 AD, Cai Lun (蔡伦) invented paper using a mixture of mulberry leaves, fish nets, rags and hemp. Specially perfumed sheets were made for use in the Emperor’s toilet, and by the early 14th century millions of packets were produced a year. Public conveniences in Britain became popular with the Great Exhibition of 1851, where 827,280 visitors chose to spend a penny to use one of George Jennings’ ‘Monkey Closets’ in the Crystal Palace Retiring Rooms. However, one Chinese visitor to Britain in the 1860s was appalled to find no purpose-made toilet paper: ‘Westerners love to be clean,’ he noted in his diary. “Their bathrooms and toilets are extremely clean, however they use newspapers and books together with other reading materials in the toilet to wipe their filth away, They don’t appreciate the value of written works.”

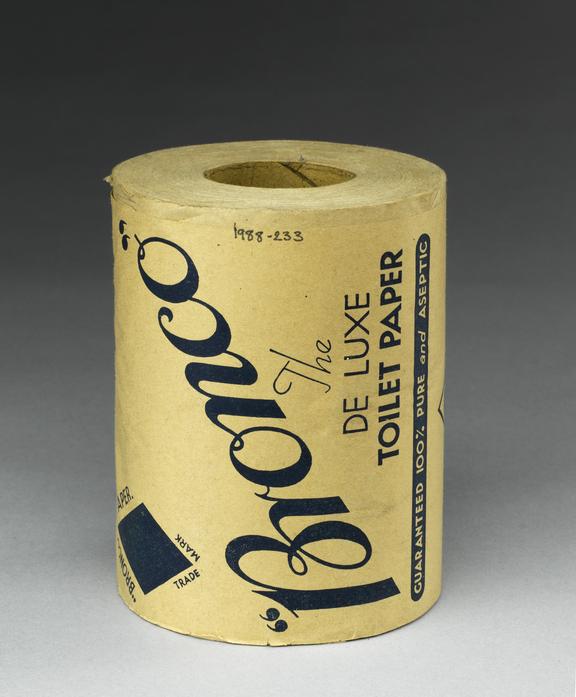

Mass manufacture first occurred in the USA in 1857, when Joseph Gayetty introduced his brand of ‘therapeutic paper’, each sheet soaked in disinfecting medicinal oils; it was advertised as ‘the greatest discovery of modern time so far as alleviating and preventing human suffering is concerned’. The first perforated toilet paper produced in rolls, as we use it today, was invented in 1879 by British businessman Walter Alcock. The British Perforated Paper Company product, manufactured in Hackney Wick, was not as soft, splinter-free or absorbent as we now expect, but was rough on one side and shiny on the other. In the 2.3 million objects in its collections (with the exception of this symbolic Greenpeace protest), the V&A has no examples of toilet paper, now a multi-billion pound industry, and surprisingly few of sanitaryware, but over the road at the Science Museum they have a roll of Bronco, the not-so ‘De Luxe Toilet Paper’ produced by The British Perforated Paper Company in the 1930s and advertised with the slogan, ‘Bronco, for the bigger wipe’.

The Science Museum also has four rolls of ‘Kleenex Quilted’ produced in 1997 with a Penrose tiling embossed design. As design critic Alice Twemlow notes in an essay of the marketing of toilet paper in the magazine Dirty Furniture, brands with comforting names like Purex, Cushelle, and Velvet use images of cupids, fluffy clouds and Labrador puppies in their advertising: “The hope is that these images will befuddle us sufficiently to prevent us from considering the lack of any real technological innovation in toilet paper over the past 120 years, and to postpone any self-reflection on what we are actually doing with it, which is far from nesting in it, seeking emotional comfort in its embrace, or, unfurling it along the corridor…”

It was perhaps this insulating sense of emotional comfort that buyers sought with their recent hoarding and nesting. In Purity and Danger (1966), the anthropologist Mary Douglas noted that “reflection on dirt involves reflection on the relation of order to disorder, being to non-being, life to death.” As we became a nation of germophobes, with every journey into the dirty public sphere seeming to involve mortal danger, the buying of toilet roll seemed to offer some kind of defence against the invisible enemy, a reassuring sense that you had prepared for the battle. Sigmund Freud connected the anal phase of a child’s development with the learning of control, and hoarding with anal retentiveness. As we all became exiles in our own countries, to cocoon ourselves in toilet paper, in the face of contagion, seemed to offer a final, precarious safety line.

Further Reading:

‘The Soft Sell’, Alice Twemlow, Dirty Furniture, 3/6 – Toilet, October 2016.

‘What Everyone’s Getting Wrong About the Toilet Paper Shortage’, Will Oremus, Medium, 2 April 2020. h

‘The Psychology of Why Toilet Roll, of All Things is the Latest Coronavirus Panic Buy’, Scottie Andrew, CNN, 9 March 2020. h

‘The Issue with Tissue: How Americans are Flushing Forests Down the Toilet’, Jennifer Skene, Natural Resources Defence Council, 2019.

Bathroom, Barbara Penner, (Reaktion, 2013).

Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, Charles Mackay, (1841).

From the Collections:

Greenpeace toilet paper, lithograph print, 1991

Greenpeace anti-pollution ephemera; a toilet roll wrapped in paper and printed with European flags. Britain, then pouring large volumes of sewage straight into the North Sea, was known as ‘The Dirty Man of Europe’, and the Union Jack therefore incorporates a skull and crossbones at the centre.

Man Selling Toilet Paper, Watercolour, ca. 1790.

Paper was invented in China by Cai Lun, a Chinese official working in the Imperial court during the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), supposedly inspired by the nests of paper wasps. Early paper was used for used for wrapping and writing, as well as for toilet paper, tea bags, and napkins.

WeChat GIF, 2017, Animation depicting a puppy offering a roll of toilet paper.

In a bid to combat thieves of toilet paper, customers in some public toilets across China have to use their smart phones to scan a WeChat QR code on an automated dispenser before sheets of toilet paper are issued.