Reopening of UK universities under Covid-19 has been subject of heated debates in recent months, with approaches to managing student accommodation during the pandemic among the most contested issues. One prestigious English university made headlines this summer for introducing new student accommodation contracts, which made possible eviction at short notice should new pandemic restrictions come into force. Elsewhere in England, challenges of social distancing meant significant increases in rent as twin rooms were turned into singles and students were charged double as a result. In Scotland, on the other hand, new legislation has been introduced to better manage the challenges of student living and protect students in these uncertain times.

The need to attract students not only back to campus, but also to their university-owned and supposedly Covid-safe accommodation, was, of course, an issue of university finance (the university accommodation sector is today worth a staggering £53 billion). But it was also an important part of offering students the kind of ‘student experience’ they have grown to expect. As Carla Yanni, author of Living on Campus: An Architectural History of the American Dormitory puts it, “residence halls are not mute containers for the temporary storage of youthful bodies and emergent minds…” they embody the “educational ideals of the people who built them.” This new rush back to campus during global pandemic brought into sharp relief the ideological commitments of the UK higher education sector today. The idea of ‘student experience’ goes hand in hand with the rise to prominence of dedicated, often purpose-built student accommodation. Living on-campus is a characteristic manifestation of a particularly Anglo-American educational ideology motivated by a commitment to ‘socialisation’ through social interaction in and outside of the classroom. Communal student accommodation embedded within the university space is an important tool of such a carefully constructed model of education.

While most of the oldest European universities, including Bologna, Sorbonne, and Utrecht did not offer substantial dedicated student accommodation up until the 19th century, in the UK and the USA living on-campus has always been an integral part of university education. At Oxford and Cambridge, medieval monasteries served as the architectural precursors of the characteristic quadrangle architectural model of college accommodation (which in turn became a model for many American college buildings, including the Thomas Jefferson-designed Woodburn Circle at the West Virginia University, The Quad at Harvard, and the Old Campus at Yale). Notably, Harvard’s first governing board thought that provision of on-campus accommodation, integrated into the college space and separate from the world outside of it, provided a unique advantage to learning. Cohabiting as part of this scholarly community, which studied, ate, slept and socialized together was to create America’s first class of leaders. University and college accommodation in this Anglo-American model, then, was designed to construct and maintain cultural norms and hierarchies and to encourage socially acceptable forms of interaction. When University College London was first established in 1826, its critics saw lack of residential accommodation provision as proof that this new institution was no real university at all.

As access to university education increased, and the higher education sector expanded dramatically, a boom in construction of dedicated student housing also followed (e.g. in 1958, the University of California could house 2,900 students across all of its 9 campuses; by 1970 its capacity had increased to 20,000 residential spaces; in the UK, 67 new on-campus student halls were built across the country between 1944 and 1957, supported by new dedicated government funding). And while the post-war university accommodation might have become a somewhat more democratic space, the idea of ‘student experience’ remained central to the university’s institutional mission. As the authors of Which University?, the first UK university guide published in 1964, put it, “many people now feel that for students to live at home is a negation of the idea of university education.” The ‘great building projects’ of the 1960s’ university expansion saw a proliferation of new campuses across the UK, often in modern and brutalist style, inclusive of comprehensive on-campus accommodation provision. Today, in the UK over 80% of all full-time students leave home for study. Almost 50% of these students live in purpose-built student halls. In Ireland, on the other hand, nearly half of all undergraduate students live with their parents and in Australia students are more likely to live in their family home than anywhere else while at university. Across Europe, only 18% of students live in dedicated accommodation.

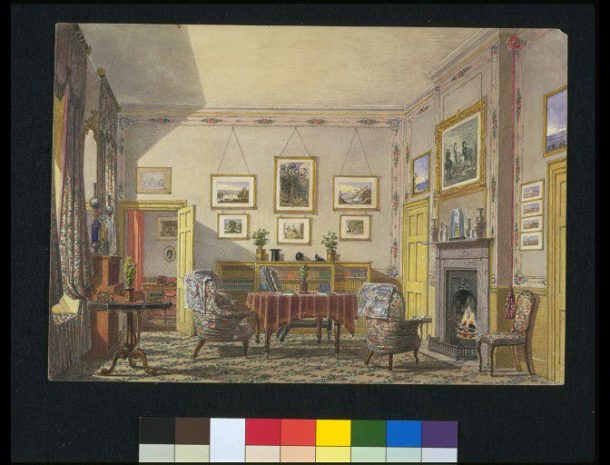

The role of student housing in the UK is such a central part of student experience that Times Higher Education – a leading trade publication for the higher education sector – now publishes a league table ranking the top 50 student accommodation halls in the UK. A far cry from student accommodation blocks of only 20 years ago – somewhat shabby, a tad smelly, furnished with the least comfortable beds, and decorated with compulsory garish curtains – student accommodation blocks of 2020 are increasingly designed to impress. The ‘Top Ten Instagrammable Student Halls’ of 2019 include the Stay Club at Colindale, London which hosts an in-house nightclub, features a picturesque roof terrace, a cinema room, and a lounge area that’s wall-lined with vinyl records as well as Scotway House in Glasgow, ‘furnished with playful neon art, millennial pink velvet seating and lush green hanging plants.’

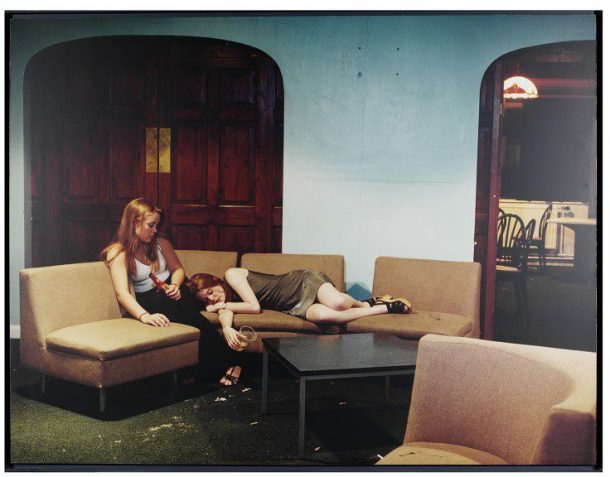

What has not changed with the arrival of the ‘luxury’ student accommodation block, however, is the temporary nature of student accommodation. A student room, an exact copy of the other 300 rooms in a purpose-built student accommodation block, is a space of transition into the freedom and independence of adulthood (with few of its responsibilities). It is never designed to feel like home. In times of Covid, when home has come to represent a new kind of intense and enforced domesticity, this unhomelike space has posed unanticipated challenges of experiencing the pandemic. Communal bathrooms might have given way today, for the most part, to en-suite showers and communal dining halls might have been replaced by modern kitchens in self-catered student flats, but these spaces remain designed for communal living, they are designed to enable and encourage interaction. That is, it is a model of living which makes social distancing challenging at best.

As universities prepared to welcome their students this year, assurances of Covid-19 secure accommodation provisions were a-plenty. But reports of student Covid-19 cases started proliferating almost as soon as students returned to universities. According to data collated by UniCovidUK, on 2 November 2020 there were 34,555 reported student cases across 119 UK universities. Student accommodation blocks are now new Covid-19 hotspots – “the care homes of the second wave of the pandemic,” as The Guardian’s Jonathan Wolff put it – and heavily contested spaces of living in times of Coronavirus. Monitored by private security firms, under strict lockdown rules, the student accommodation block has become one of the most heavily policed spaces of the pandemic. This necessary shift in the way university space is inhabited, and transformation of ways in which bodies in that space are monitored and controlled, has made visible the disciplinary function of educational institutions in new and unexpected ways. And while discipline is always, as Michel Foucault tells us (see: Discipline and Punish), a characteristic feature of education, these new restrictions imposed on student accommodation blocks have proven controversial not as a means of controlling the pandemic but because they invite and prohibit at the same time the very approach to ‘student experience’ that makes communal student accommodation a necessary component of university education.

Restrictions placed on students in dedicated accommodation blocks where outbreaks were recorded have been particularly strict, far surpassing restrictions imposed on those self-isolating elsewhere. As a result, grassroots activist groups have been emerging on campuses across the UK. Earlier this week, introduction of fencing around halls of residence in Manchester – a new Covid-19 control measure – led to a wave of student protests in the city. The ‘Cut the Rent’ campaign has called rent strikes in a number of major university cities (with 1,000 students pledging to join the rent strike in Bristol alone). Others, including the ‘Students Before Profit’ group have been campaigning for better conditions for students experiencing lockdown in halls. Demands from different groups vary but pressures to release students from their accommodation contracts has been a prominent feature of these campaigns. As a second English lockdown was being announced last weekend, and speculations of a planned pre-Christmas university lockdown proliferate, increasing numbers of students have been choosing to, quite unsurprisingly, defy the guidance, leave their student accommodation and get back home before new restriction come into force. This new, unseasonal exodus of students from halls – a familiar ritual which repeats every term – is a telling manifestation of the changing function, meaning and perception of student halls in time of Corona. No longer hubs of student activity and hardly essential to ‘student experience,’ which under Covid-19 is socially distanced and predominantly lived online, student halls have become a poignant symbol of commercialization of the higher education sector and stark expression of the broader impact of economic pressures during the pandemic.

Related Objects from the Collections:

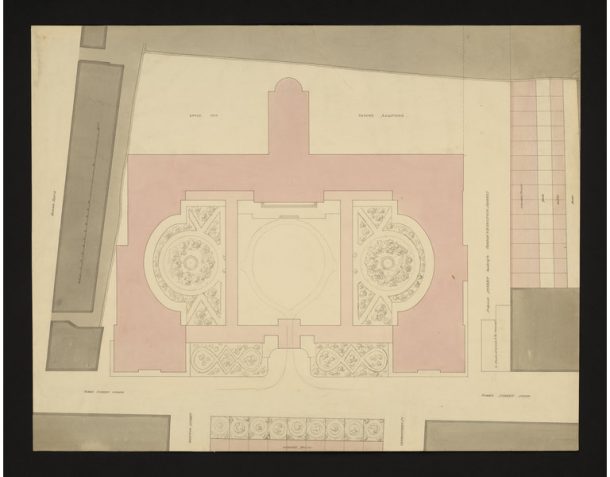

‘Design for University College Buildings, Gower Street’, Charles Robert Cockerell, 1827 (V&A: E.2091-1909)

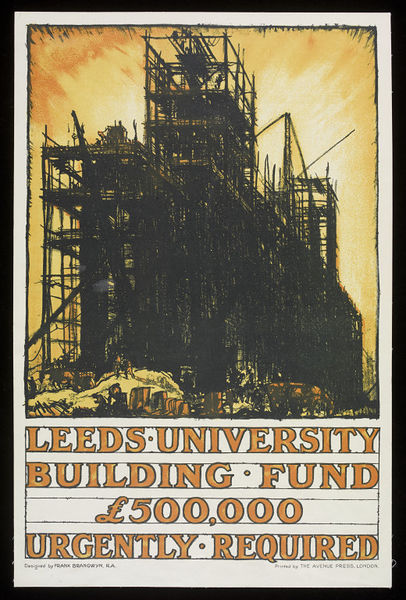

‘Leeds University Building Fund’ (poster), Frank Brangwyn, 1925 (V&A: E.2598-1931)

‘Untitled May 1997’, Hannah Starkey, UK, 1997 (V&A: E.491-1998)

Seminar Chair, Selman Selmanagic, 1947, Dresden (V&A: W.7-2007)