If there is any common denominator of living through a pandemic, it is perhaps the feeling of disconnection. Almost a full year since the startling shock of that first lockdown, Covid-19 has changed our relationships to public space and to other people. We are used to carving wide berths around others on the street, and avoiding shared touch. In the absence of natural, daily connection with others, we’ve witnessed a return to the handmade, and the things we have at home. Radio is a quiet force in this resurgence of the simple, as a vehicle for connection.

Almost every household in the UK has an analogue radio, radio in their car, or access to digital radio on a phone or computer. According to Radio Joint Audience Research (RAJAR), almost 90% of adults in the UK listen to the radio weekly. All three national lockdowns have seen a marked increase in both listener numbers and listening time, as people are confined to the house or working from home. In the early anxious days of last March, news stations saw a particular boost, as people turned to radio as a trusted source of information and reassurance. Many others, when interviewed, state that radio simply keeps them company.

Radio has long been considered a dying medium, overtaken first by television, and since by the internet. But there is something evergreen in radio’s humble power, which derives perhaps from its relationship to time. Unlike the internet, where everything lives forever, or the podcast – available always, to which you listen independently – radio is essentially ephemeral, and anchored to the present. Digital playback services aside, listening to the radio live involves a kind of kinship, however fleeting or subconscious, with others listening elsewhere.

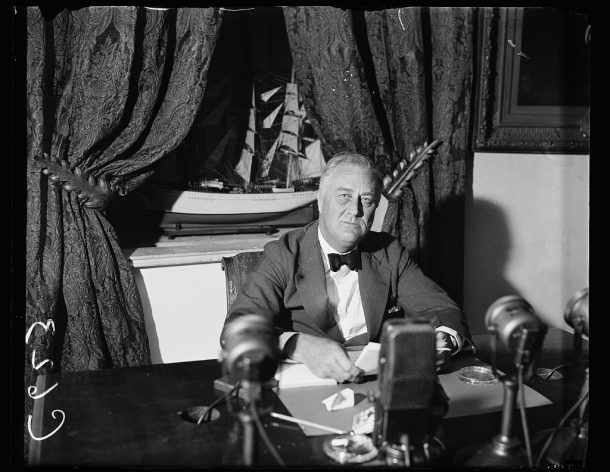

Historically, radio has been used to great effect in moments of national urgency. Franklin D. Roosevelt harnessed the intimacy of listening and the sheer reach of radio during his tenure as US President. Between 1933 and 1944, Roosevelt delivered around 30 radio addresses to the nation. Although serious in content, his ‘Fireside Chats’ were characterised by an informal, conversational style, and were designed to feel for the listener as though the President was speaking directly to them. Initially intended to garner support for Roosevelt’s New Deal policies, the chats became an important source of hope and security throughout the Great Depression and World War II. Their nickname conjures images of families gathered by the fireplace, radio on the mantel, listening collectively at the hearth.

The radio has always been a powerful political instrument, but it is not necessarily complex technology. The first radio was patented in 1896 by Guglielmo Marconi, and by the 1920s ‘amateur’ radio was broadcasting all over the world. The accessibility of radio clashed with desires for national control. A 1933 conference in Lucerne officially assigned frequencies to European countries so they could manage broadcasts at home and across their colonies in the Middle East and Africa. One such example was the Palestine Broadcasting Service, established in 1936 and modelled after the BBC, which ran until the end of the British Mandate in 1948 and was then taken over by Palestinian broadcasters.

Radio has always been both an instrument of colonialism, but also a medium for resisting it. In Algeria, clandestine radio transformed the way independence was understood and imagined in the minds of Algerian listeners. In 1956 the Voice of Algeria began its broadcasts, uniting the Algerian people in solidarity and resistance. Although the French colonial government confiscated radio sets and jammed the Voice’s frequencies, its messages got through. As Frantz Fanon writes, “buying a radio, getting down on one’s knees with one’s head against the speaker, was no longer just wanting to get the news…it was hearing the first words of the nation.” (from the English translation of A Dying Colonialism, 1965)

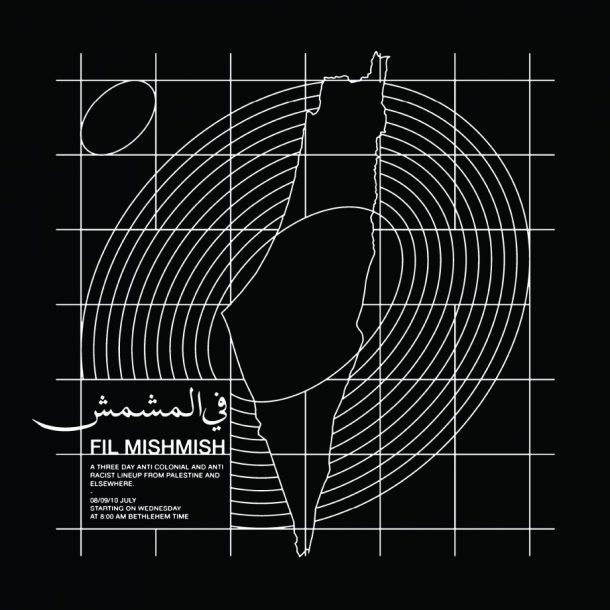

The pandemic has been a catalyst for new online radio stations across the Middle East and North Africa. In Palestine, Radio al-Hara (the Neighbourhood Radio) began broadcasting on 20 March 2020, run by five friends based between Ramallah, Bethlehem and Amman – architects Elias and Yousef Anastas, artist Yazan Khalili and graphic designers Saeed Abu Jaber and Mothanna Hussein. The station’s programming harnesses the reach of the organisers’ vast networks, and Radio al-Hara quickly became a site for free expression and global communion with others, programmed by its own listeners. Tune in to hear artist Jumana Emil Abboud telling Palestinian folk tales; Raja Khalidi addressing the economy; an hour of 1960s Black nationalist poetry by The Last Poets; and musicians and DJs from all over the world playing sets from their sofas. In July 2020, Radio al-Hara organised a three-day protest-broadcast, triggered by the proposed annexation of part of the West Bank, which was mirrored on radio platforms from London to Tunis. After the port explosion in Beirut on 4 August 2020, the station ran a 30-hour fundraiser stream to support those affected. In her recent ‘Love letter to radio’, Rayya Badran observes, “These recent communal experiments with radio…are incredibly exciting, not only because they summon us to listen, alone and together, but to harness a transnational collectivity that is otherwise made impossible by harsh and imposed borders.” (from ‘The Idea of Playback’, presented at How to walk through a labyrinth, Mosaic Rooms online event, 2 July 2020.)

Such transnational potential is particularly meaningful in Palestine and across the Middle East, but radio is inherently planetary technology. Like light, radio waves are a form of electromagnetic radiation, around us all the time, oscillating between the scale of a body and a building. Listening to the radio means tapping in to something elemental – to waves bouncing between the ionosphere and earth, to sound sizzling across borders. Radio is pirate and planetary, public and clandestine, reassuring and revolutionary; it resounds during moments of national and global urgency. While we remain, for now, home-bound and separate, radio’s power to connect us has rarely felt so precious.

Further Reading:

Listen to Radio al-Hara here, and to other online radios from the Middle East – many of which began during the pandemic – on Yamakan.

Did Marconi’s fake his famous trans-Atlantic broadcast? ‘Faking the waves’, Laurie Margolis, The Guardian, 11 December 2001.

Yasmina Reggad’s we dreamt of utopia and we woke up screaming is an ongoing research project that takes as its starting point the radio shows of Algerian liberation movements in the 60s and 70s.

Radio Earth Hold is a research collective making and commissioning broadcasts about histories of the radio and sonic solidarity. Their first project, The Colonial Voice, addresses the history of radio in Palestine.

From the Collection:

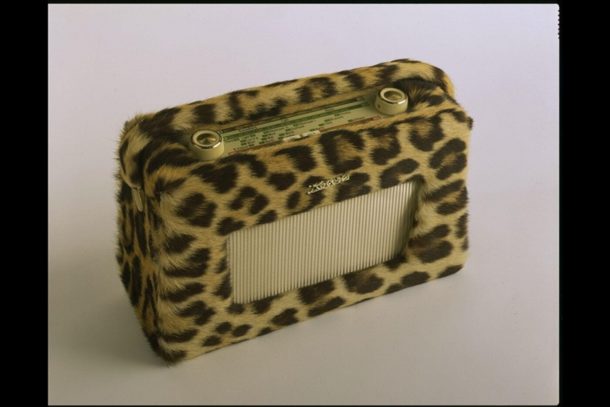

Roberts Model R500 radio, Roberts Radio Co Ltd, UK, 1964 (W.33-1992)

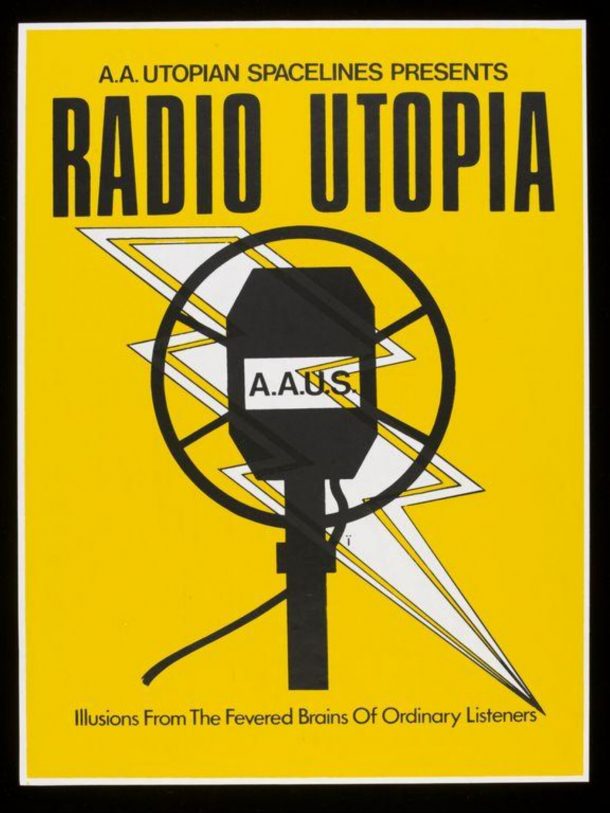

Radio Utopia poster, Greenwich Mural Workshop, Great Britain, ca. 1975-1984 (E.102-2011)

Credit card radio, Sony, Japan, c.1985 (W.20-1992)

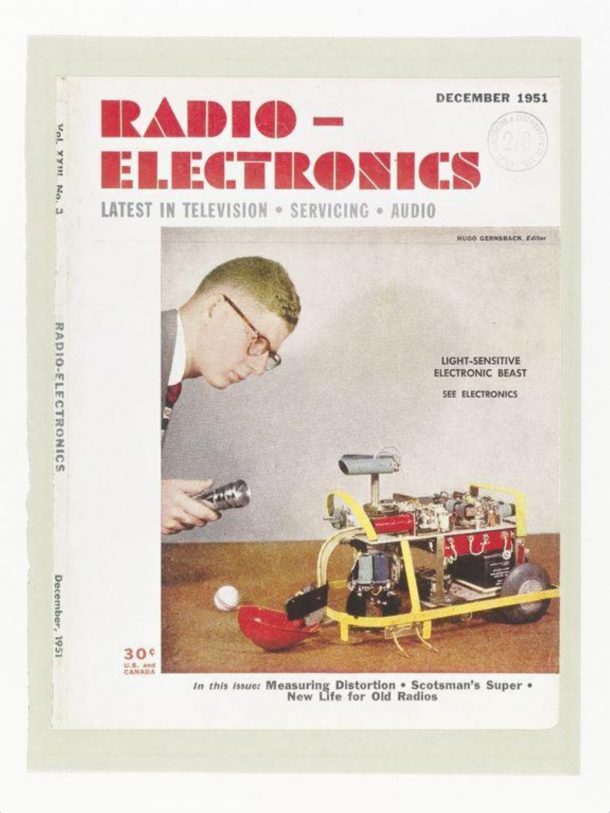

‘New Life for Old Radios’ print, Eduardo Paolozzi, UK, 1972 (CIRC.540-1972)

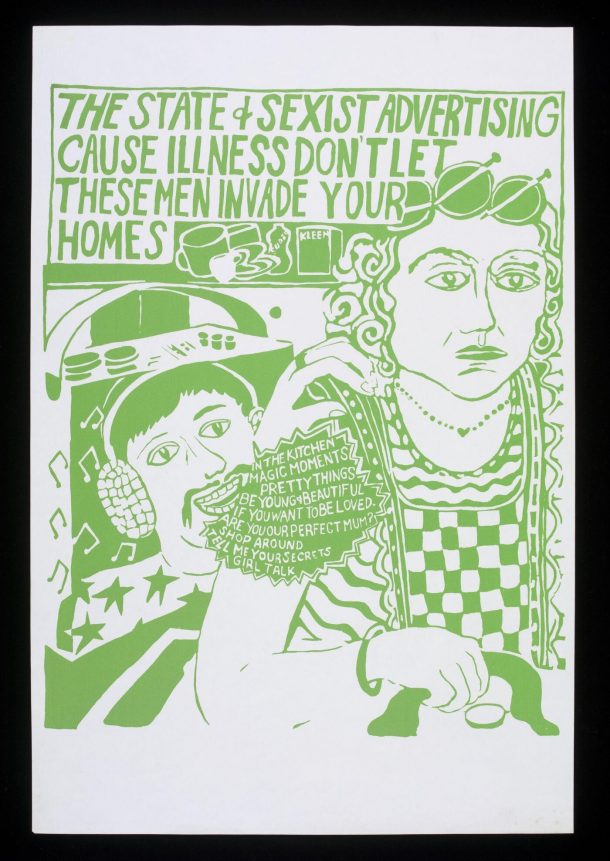

‘Disc Jockey’ poster, See Red Women’s Workshop, UK, c.1974 (E.85-2011)

Rachel has some funny ideas about Palestine and Israel

Sadly, very few are fact-based

She drinks a lot of Hamas Kool-Aid.