I still remember the first time I accidentally bumped into a passer-by in a crowded park. It was the first weekend of lockdown and we, as Londoners, were still acclimatising to new codes for sharing public green space. We were both making our way around a woodland corner, giving it a wide berth in line with the obligatory 2-m ‘social distance’, but both took steps in the wrong direction on a narrow path. Our momentary encounter was brief and apologetic. Ten weeks on, public parks continue to be busy spaces of the pandemic. They have also emerged as arguably one of the most contested public realms of the lockdown experience.

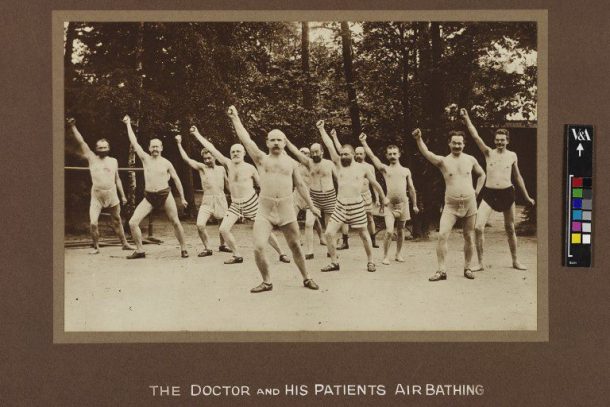

The importance of urban green space for public health has long been known, and accordingly from the outset of the lockdown outdoor exercise has been permitted by UK government regulations. Restrictions for going outdoors have gradually eased since March – from once-a-day local walks to ‘unlimited’ outdoor exercise and most recently, permission to have a ‘socially-distanced’ picnic. For those living in crowded cities, public parks have been given a vital role for restoring our mental and physical well-being, a space of collective healing during COVID-19. Such beliefs in the restorative capacities of the natural environment are not new, and indeed ‘nature cures’ have long been associated with boosting immunity and tackling respiratory health in particular – from the healing powers of sunshine (‘heliotherapy’) to the vital necessity of fresh air (known in nineteenth- and twentieth-century European sanatoria as ‘air bathing’). The more intangible, emotional joys of reconnecting with the natural environment are also powerful here. Early lockdown Instagram feeds marked the arrival of spring with endless documentation of tree blossoms as Londoners walked around more, and perhaps spent more dedicated time in green spaces than ever before. On this level, our reconnection with public parks during COVID-19 may have a lasting and vital benefit, as both a timely re-kindling of our close need for trees and green spaces and a re-appreciation of the crucial role these play in rebalancing our polluted urban habitats. Understanding our entanglement with the natural world has never been more important.

However, our use of public parks during this pandemic has not gone uncontested.

For one, public green space has been the arena for us confronting a dramatic change to social codes. Park use in the first phase of UK lockdown had the memorable slogan of ‘keep moving’, where quite literally, we were no longer permitted to sit. As parks were recalibrated for ‘COVID-safe’ use, the traditional objects that furnish our green public realm were also taken out of use. From police lines cordoning off brightly-coloured playgrounds to taped-up picnic tables and benches, the warning signs that we are in a pandemic are still constantly visible.

New signs have entered this sphere too: the graphic of two figures separated by an arrow is the code we now enact. Other classic park design features, such as meandering lanes and narrow paths, have also been tested as we try and figure out how best to keep ‘social distances’ with ease in crowded parks. Venturing off-path and traversing a rolling green expanse may be the best option so far, but it is also clear that old forms of casual strolling can no longer apply. As users, we are now finding new paths through these designed, landscaped spaces. French philosopher and social scientist Michel de Certeau explored such ‘tactics’ of walkers in his theories on the ‘practice of everyday life’, and now as ‘everyday life’ has changed, our walking reimagines these spaces again.

Public parks have a long history as a stage for diverse forms of behaviour on display: from the conspicuous promenading in fashionable attire that was performed in London’s Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, to the unspoken codes around group sport and safely flying frisbees today. German choreographer Pina Bausch created an homage to the parade of behaviours in public parks with ‘1980’, a now famed work of her dance/theatre company in Wuppertal. Now, as the realities of COVID-19 continue, public parks are the setting for leisure during pandemic: requiring self-regulation and distancing; they are the stage for new choreographic practices of collective trust. Instances where such trust was reportedly considered lacking saw London parks introduce wardens to monitor behaviour. Structures for issuing fines exist as well.

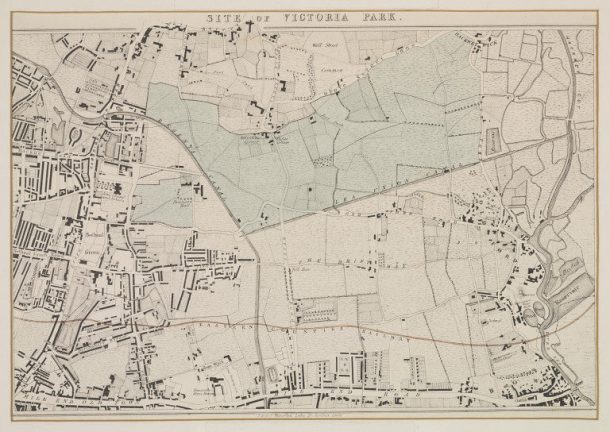

The contested experience of public parks during this pandemic has also sparked important debate over equitable access to green space. In the case of London, the UK’s most densely populated region, the pressure on public parks has been high. Google’s COVID-19 response venture of ‘Community Mobility Reports’ (which has been rightly flagged for privacy concerns) mapped global data patterns on park visitation, with London data showing a 61% increase compared to pre-pandemic use. Successive weeks of lockdown saw surges in park visitor numbers, with many reported cases of overcrowding and threatened closures over public health concerns. The outcry over the temporary closure of Brockwell Park in South London in April proved a key turning point, throwing into sharp focus the long-existing inequalities of green space experience in London – an enduring challenge for urban planning in our capital. For many, in the absence of the luxury of a private garden or even a balcony, public parks have been the only outdoor green spaces to offer respite from lockdown confinement. And access to parks remains unequal, with a Guardian report highlighting the city’s wealthiest wards having the highest proportion of spaces at 35%, compared to only 25% in the most deprived. Indeed, the very emergence of public parks, as distinct from commercial pleasure gardens and royal grounds, was part of a Victorian era movement to ensure fairer access. Victoria Park in East London was the city’s first purpose-designed public park that opened in 1845 with a layout by architect James Pennethorne, the design drawings for which are held in the V&A Collection. During this pandemic, Victoria Park was overwhelmed with visitors, resulting in tight regulations for its use.

The recent debate’s conclusive defence of the fundamental right to public park space must not be forgotten as we seek to plan for a post-COVID-19 world. As shared community assets, public parks will continue to play an important role for public health, and the wider environmental balance of our cities, as the living ecosystems and ‘green lungs’ that sequester carbon, purify our air and help slow the dangerous pace of climate change. Across the UK it is estimated there are currently 27,000 park spaces however, as the pandemic has shown, more green public realm is vital. We may look to other big cities for inspiration on enhancing access to public green space – San Francisco’s bold move to open vast swathes of golf course territory to the public during the pandemic has already sparked a petition for the UK. Urban design policy and housing developments will also need to safeguard public greenery in planning. As we return to sharing the spaces of our city again, we may also want to cast a critical eye to London’s long list of private, gated squares. New parkland design may need to take on the learnings of social distancing. And while extreme scenarios of green labyrinths may not be the direction to go, we will need to think about future-proofing. For us as individuals, this moment also presents an opportunity to re-frame and expand how we enjoy urban nature. London is after all, technically, a forest. With over 8.4 million trees and counting, there is almost one tree per London resident. Apps such as Tree Talk offer new tools for exploring our urban habitats. Let’s think creatively about how to use this urban forest better, and grow it too.

Further Reading:

‘UK sunbathers may trigger stricter coronavirus lockdowns’, Lanre Bakare and Peter Walker, The Guardian, 5 April 2020.

‘Coronavirus: Should outdoor exercise be banned and parks closed?’, BBC News, 20 April 2020.

‘Coronavirus park closures hit BAME and poor Londoners most’, Pamela Duncan , Niamh McIntyre and Sam Cutler, The Guardian, 10 April 2020.

‘Coronavirus UK: Jenrick has ‘made it clear’ parks must stay open’, Aaron Walawalkar, The Guardian, 18 April 2020

‘The case for making golf courses public parks during coronavirus’, Quartz, 26 April 2020.

‘How the coronavirus is already reshaping the design of parks and streets in New South Wales’, Rob Stokes, The Guardian, 8 May 2020.

‘Public Parks’, House of Commons Communities and Local Government Committee, Report of Session 2016–17

‘Land for the Many’, George Monbiot (ed.), A report to the Labour Party, June 2019

London is a Forest, Paul Wood (Quadrille / Hardie Grant Publishing, 2019)

Related Objects from the Collection:

Site of Victoria Park (Print), Waterlow & Sons, London, c.1841 (E.4945-1923)

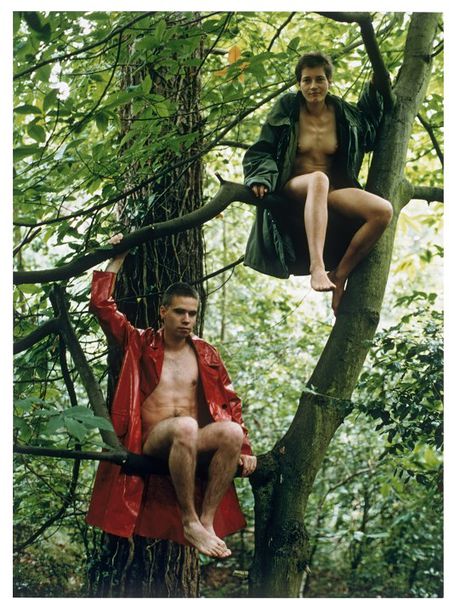

‘Lutz & Alex sitting in the trees’, (Photograph), Wolfgang Tillmans, 1992 (E.846-1994)

Huntley & Palmers trade card (Print), Huntley & Palmers, 1890s (E.1822-1983)