As we recently marked the reopening of clothing shops in England and Wales, the Office of National Statistics (ONS) has confirmed the UK clothing sector has been one of the worst sectors affected by COVID-19 restrictions. More than 17,500 stores have permanently closed since non-essential shops were forced to shut over a year ago. The fashion landscape of the British high street has fundamentally changed with familiar brands including Oasis, Warehouse and Arcadia Group’s Topshop, Topman, Miss Selfridge and Dorothy Perkins all filing for bankruptcy and ceasing to exist as brick-and-mortar shops.

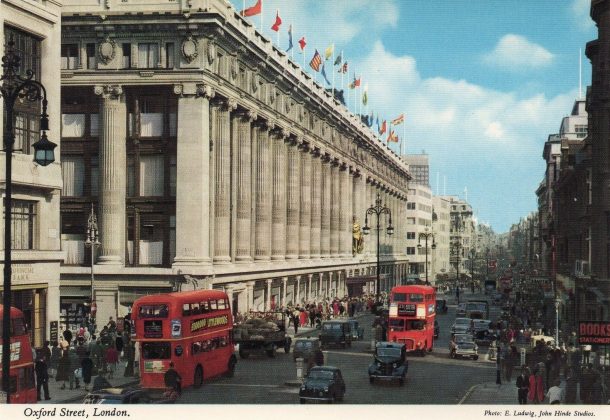

Some of Britain’s oldest and most established department stores – which have survived multiple recessions and bombing during the Blitz – have not gone unscathed; the collapse of Debenhams, established in 1778, is a particular blow. High-end department store Harrods, of 1824, and Selfridges, of 1908, have cut 450 and 700 jobs respectively as a result of the pandemic and resulting recession. John Lewis, founded in 1864, is permanently closing one third of its stores and may convert its London flagship into office space.

As someone who spent most Saturday afternoons of their teenage years trawling around Topshop’s Manchester store – seeking out the perfect polyester boob tube, cropped angora jumper or All Saints-esque vest tops and cargo pants – I mourn the loss of these British shopping landmarks. So many memories are tied to occupying these spaces with friends; clothes shopping is inherently a social activity that can’t be replicated by scrolling through pages of ready-to-wear online.

The clothing shop has been under threat for many years as consumer spending habits have shifted away from traditional in-store purchases to e-commerce. With many people stuck at home, few opportunities to get dressed up, and retail spaces remaining closed for much of last year, the pandemic has only accelerated that shift. ONS revealed UK in-store fashion sales plunged 25% in 2020, while online transactions were up 32% for the same period. This stark contrast in fortunes is underlined by online fashion retailer ASOS reportedly tripling its profits last year. Alongside fast-fashion peddler Boohoo, ASOS have acquired many of the failing high street brands listed above for their digital platforms, closing down stores and making them online-only.

Despite this trend, numerous reports have highlighted that UK shoppers are keen to return to stores. Total sales in the first week of re-opening non-essential retail shops this April saw a ten-fold increase in sales compared to the same time last year, when the UK was at the height of its first lockdown. So, what have we missed in a year of not going clothes shopping?

And what aspects of in-person retail can’t be replicated through shopping online?

Trying things on before buying is cited as a key reason for customers wanting to return to in-store shopping. Many consumers want to feel the materials, see the finish, and assess if an item suits them sartorially and is a good fit. Unlike every other area of retail, fashion is intrinsically connected with the people who wear it – designed to be worn on a body. Being physically separated from the clothes when buying online, and deciding to buy based on how things look on someone else’s body (the model), has always presented challenges for consumers and retailers alike, resulting in vast amounts of returns.

Arguably, the pandemic has made the online shopping process harder for customers, particularly with sizing given many people’s living habits have changed over the last year. Whilst online fashion retailers have benefitted from a surge in ‘lockdown’ clothing categories – namely active and casualwear – which are inherently stretchy or looser-fitting, anyone who has ever tried jeans or bra shopping online can confirm that it is problematic.

For brick-and-mortar clothing shops wanting to survive and thrive in a post-pandemic world, innovation and adaptation are key to enticing shoppers back into the physical retail space. As a source of inspiration, it’s useful to look back at some of the 20th century pioneers of fashion retail who paved the way for a new type of sartorial shopping experience.

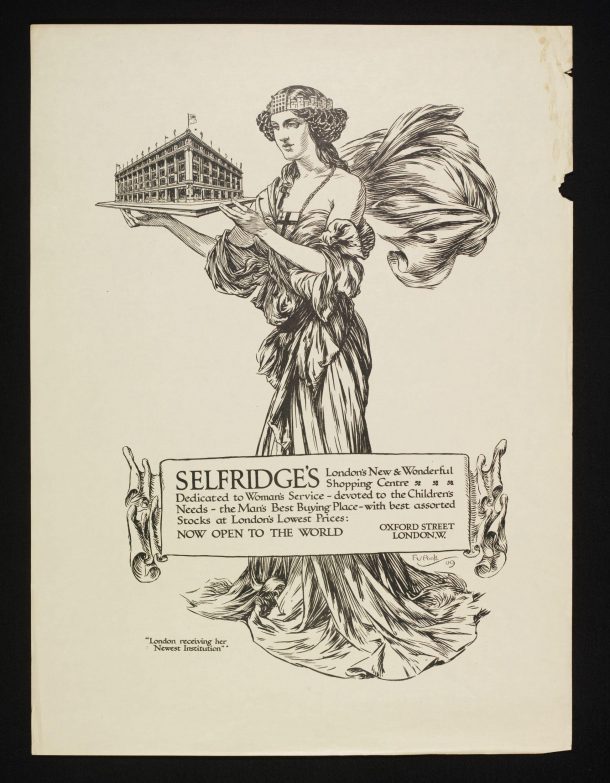

Selfridges: At a time when department stores were one of the few public spaces designed for women’s pleasure, Harry Gordon Selfridge stated ‘A store should be a social centre, not merely a place for shopping.’ His visionary approach saw Selfridges become the first department store to install women’s toilets in 1909, meaning women could spend the whole day away from the home without causing moral indignation, and ultimately led to shopping becoming a leisurely, enjoyable activity. Selfridges emphasised the experiential spectacle of shopping with an ice rink and shooting range on the roof, and theatrical shop window displays which were the first to be illuminated at night drawing significant crowds.

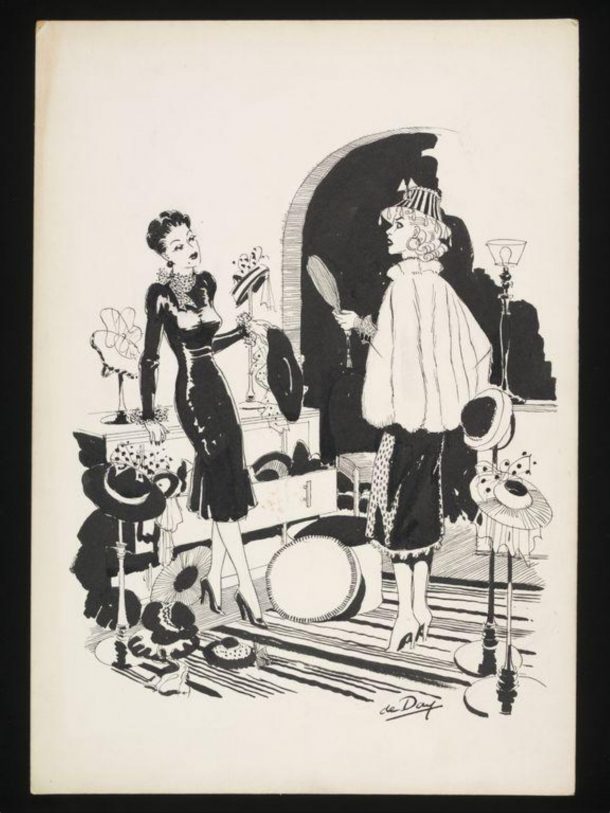

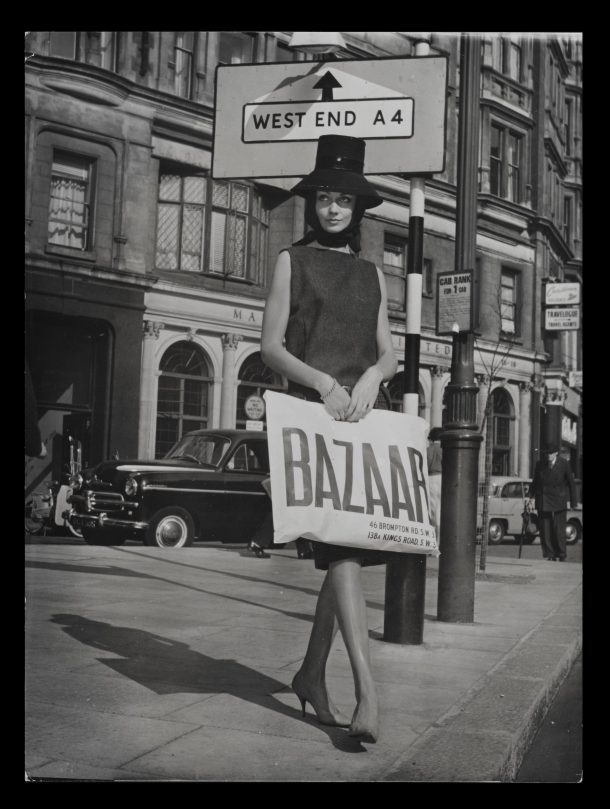

Bazaar: Mary Quant’s 1955 Bazaar boutique at 138a Kings Road, Chelsea was the forerunner to the explosion of boutique shops which happened in the late 1950s and 60s London. Bazaar transformed the retail experience playing music, serving drinks, hosting fashion shows and – for a brief time before Quant was caught out by strict trading laws – offering Saturday late-night shopping. Quant’s irreverent approach to window display, forward-thinking visual branding and marketing and constantly changing stock ensured a steady stream of repeat customers. The inclusion of Alexanders restaurant below the shop cemented Bazaar’s reputation as a cultural hub – a place to ‘see and be seen’.

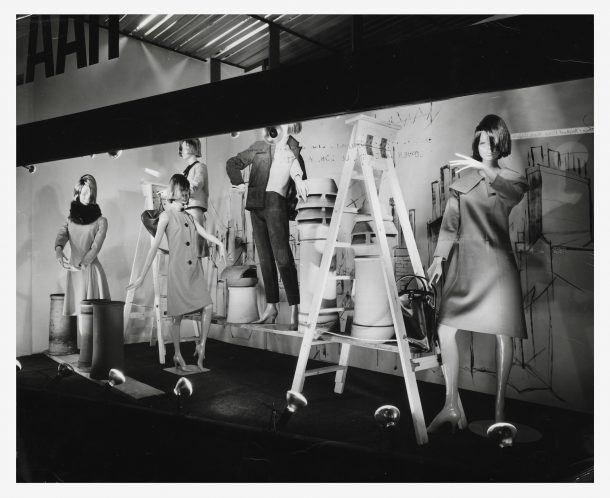

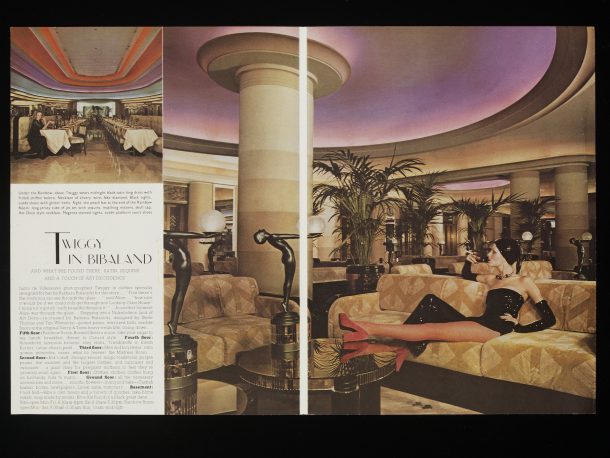

Biba: Barbara Hulanicki’s Biba began in 1963 as a mail-order business but quickly became a retail phenomenon. Its ultimate success was its affordability which set it apart from other boutiques and swiftly fostered mass-market appeal and celebrity endorsement. Each successive boutique offered the unique Biba sensorial experience; moody and dimly lit, filled with antiques and Victorian furniture and featured a communal changing room.

Big Biba which opened in 1973 was the epitome of immersive, experiential shopping; seven floors of opulent, palm-filled departments – each with a unique Biba logo – where you could buy everything from Biba baked beans to wallpaper and curtains. It attracted up to a million visitors a week, making it one of London’s most visited tourist attractions.

Other features included a flamingo-filled roof garden which lived on as Kensington Roof Gardens until 2018, and the Rainbow Room restaurant which doubled as a gig venue for bands including the New York Dolls and the Ronettes and later featured in David Bowie’s 1984 ‘Blue Jean’ music video.

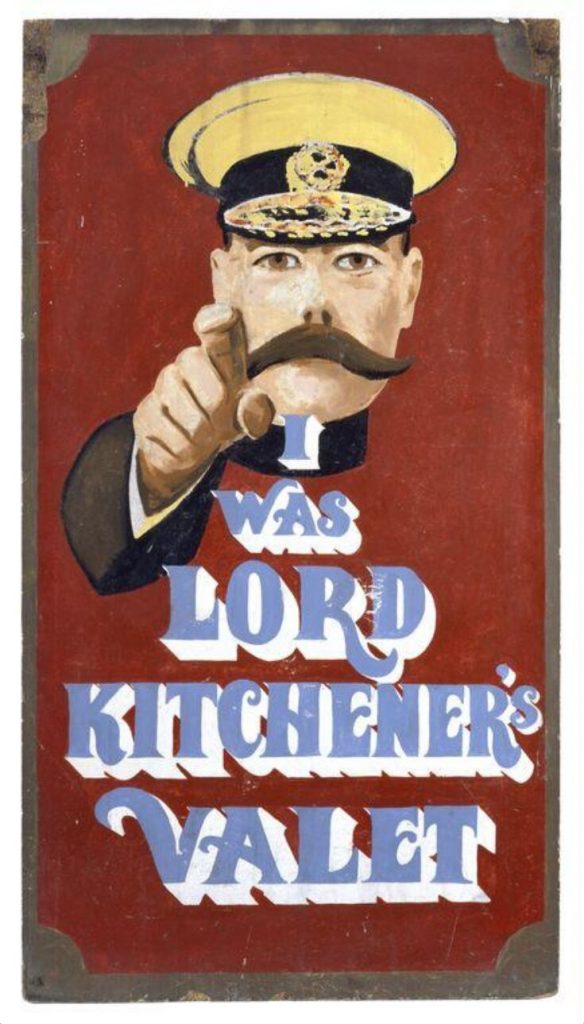

I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet: London boutique I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet’s unique selling point was its branding and merchandise. It specialised in decommissioned military uniforms bought cheaply from British Army Surplus stores and re-imagined them for the anti-establishment youth. This unique second-hand boutique gained instant success and celebrity endorsement from Jimi Hendrix, and Mick Jagger who bought a Grenadier guardsman drummer’s jacket in 1966 and wore it on the TV show ‘Ready Steady Go’ when performing ‘Paint it Black’.

The design of the shop sign directly referenced the famous 1914 armed forces recruitment poster designed by Alfred Leete which featured Lord Kitchener, then Secretary of State for War, pointing at the viewer with the words ‘Your Country Needs You’.

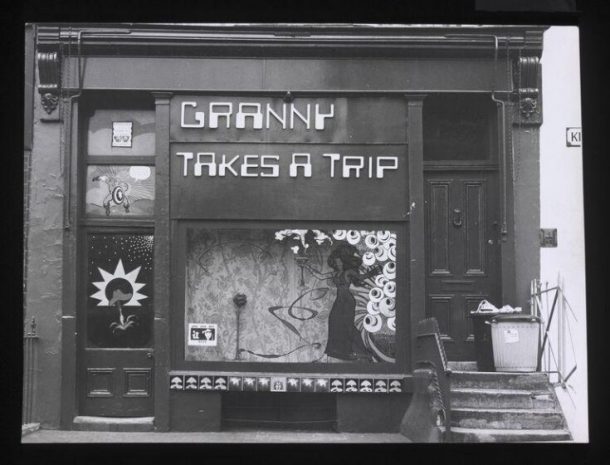

Granny Takes A Trip: or Granny’s as it was fondly known, was an emporium of re-styled, one-of-a-kind vintage fashion and floral Liberty print tailored jackets. Opened in 1966 at 488 King’s Road, the shop catered to a dedicated following of flamboyant, elite clientele including some of the most iconic musicians of the time like Pink Floyd, The Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin. The boutique became just as known for its distinctive changing façade, which at one stage was painted with a pop-art face of Jean Harlow, and later replaced with an actual 1948 Dodge car which appeared to crash out of the window and onto the forecourt.

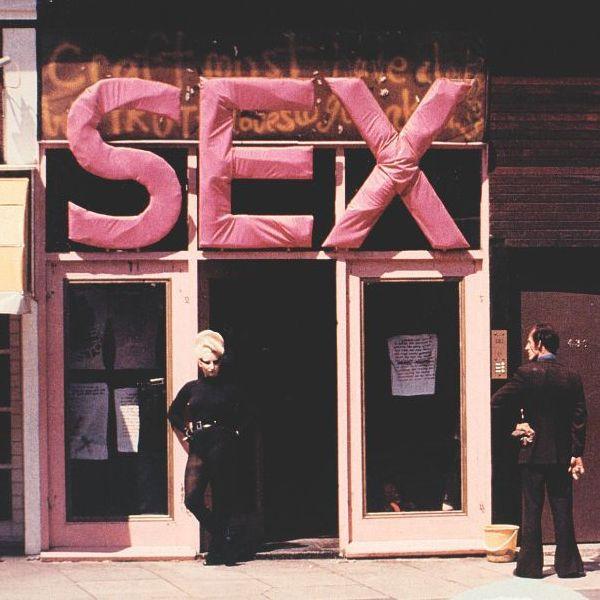

Sex: Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren’s iconic 1974 boutique ‘Sex’ at 430 Kings Road, Chelsea is a great example of brand reinvention and creativity. The pair changed the shop’s name and décor to suit the clothing, operating as Let it Rock, Too Fast to Live Too Young to Die, Sex, Seditionaries and finally Worlds End, between 1971 and 1979. ‘Sex’ was perhaps the most notorious incarnation, which was decked out in spongy rubber material and featured pink rubberised letters ‘SEX’ above the door. The boutique quickly gained a cult following selling fetish wear to sex workers, those with ‘underground’ sexual tastes, and young punks brave enough to wear the look.

These visionary fashion retailers all underline the possibilities of physical retail space. It’s not just about creating a site of transactional sales, but instead it’s about immersive, social spaces to connect, explore, and dream. As we conjure up what a post-Covid world might look like, let’s keep some room for the clothing shop and its enduring radical potential.

Related Objects from the Collection:

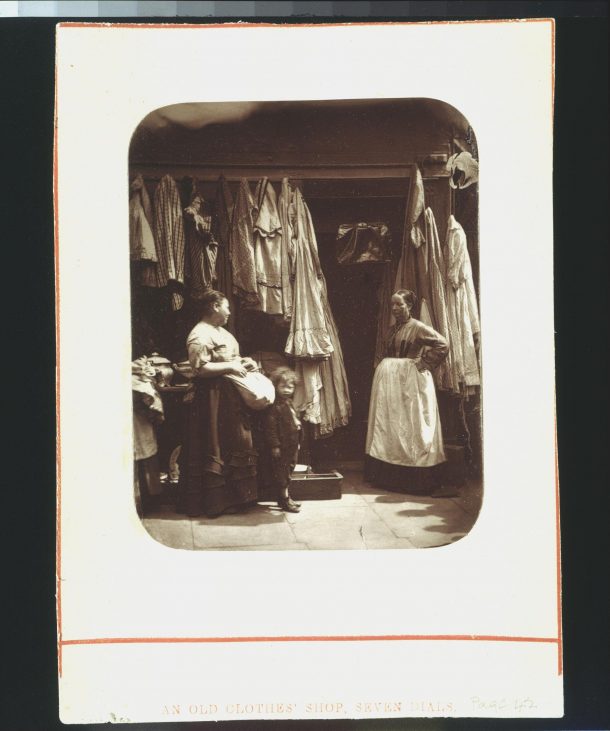

An Old Clothes Shop, Seven Dials, photograph by John Thompson, London, England, 1877-1878 (PH.330-1982)

Magasins du Bon Marché, photograph by Eugène Atget, Paris, France, 1926 (PH.1161-1980)

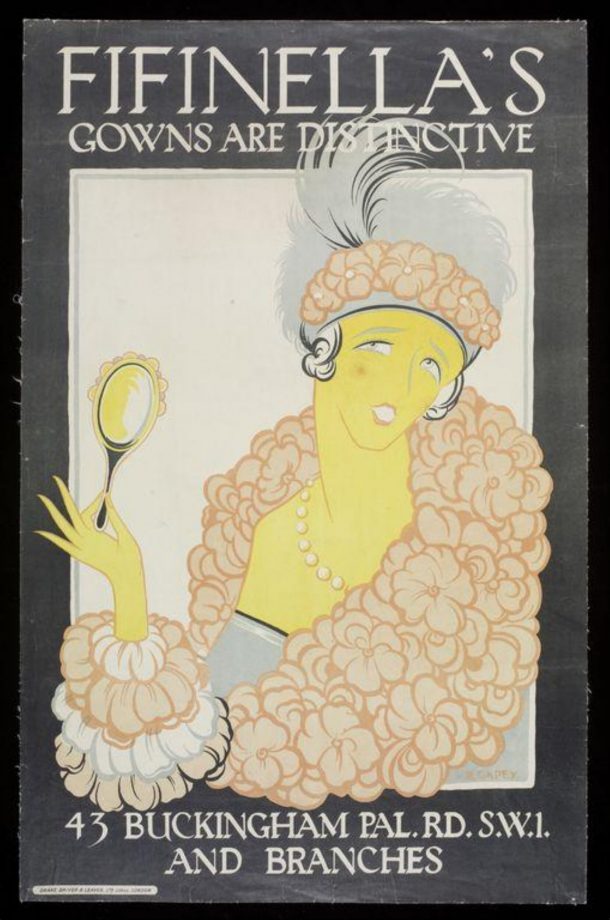

‘Fifinella’s Gowns Are Distinctive’ poster advertising the shops of Madame Fifinella, court dressmaker, Buckingham Palace Road, London. Design by Reco Capey, Great Britain, c.1923 (E.636-1923)

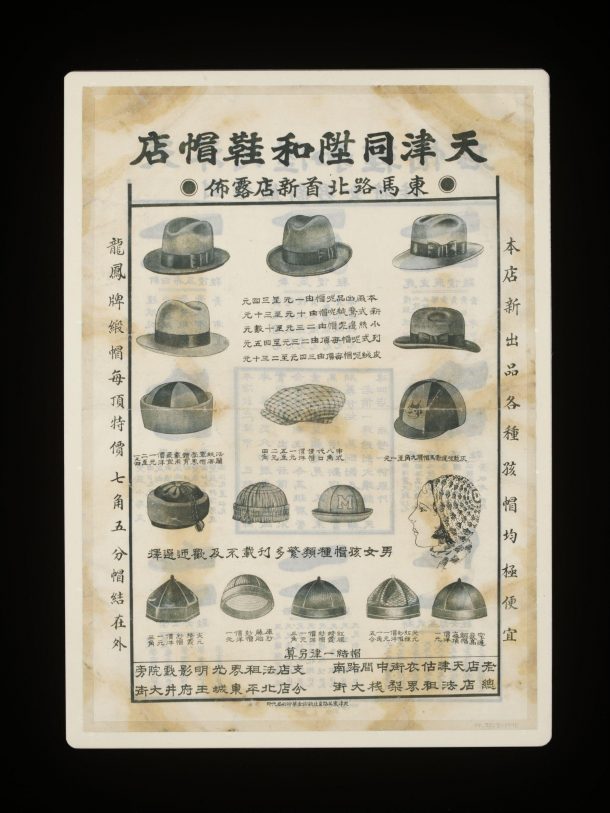

Advertisement for Tong Sheng He hat and shoe maker, Tianjin, China, early 20th century (FE.32:3-1995)

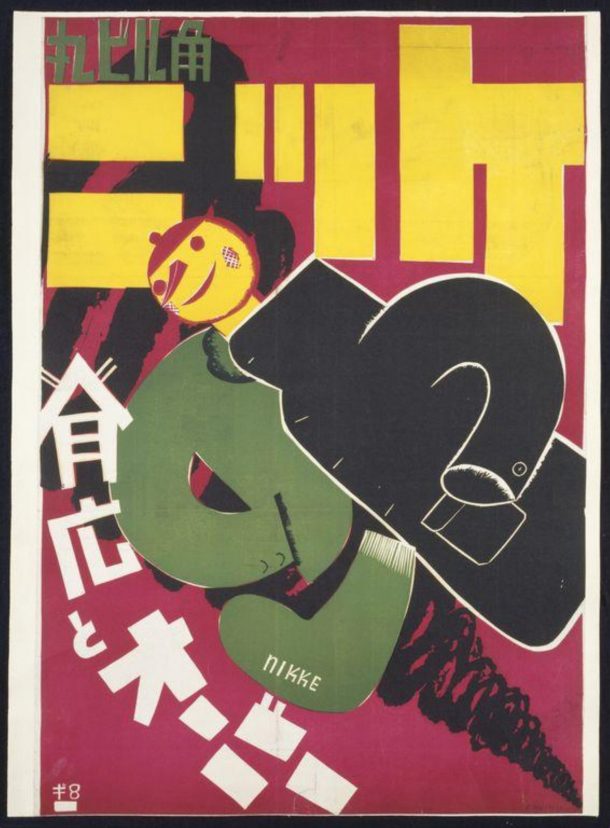

Poster for Nikke clothing store by Gihachiro Okuyama, Japan, c.1930 (E.184-1935)

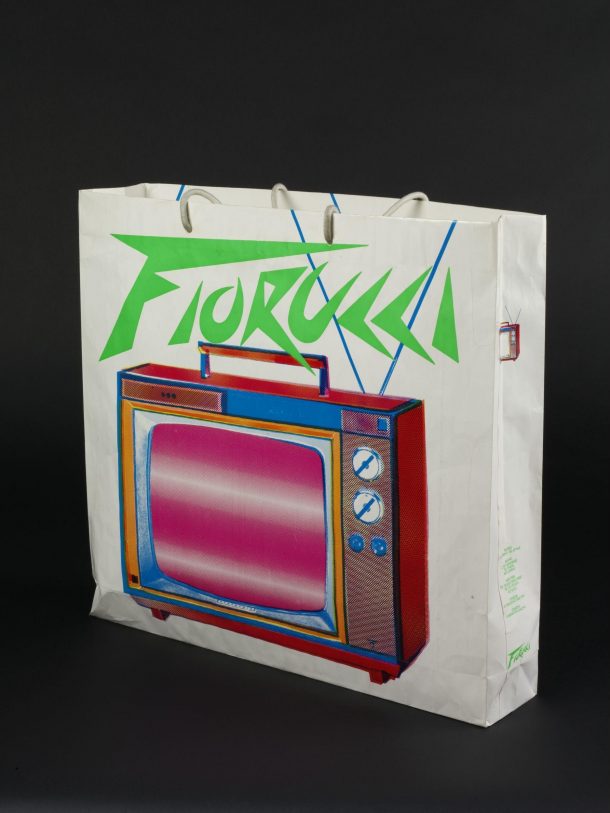

Fiorucci Carrier bag by Eric Schemilt Designs Ltd, London, 1978 (E.896-1978)

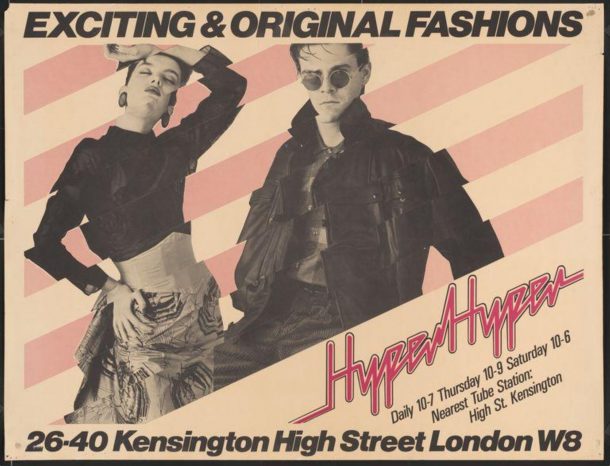

Hyper Hyper shop launch poster, London, 1982 (E.575-2012)

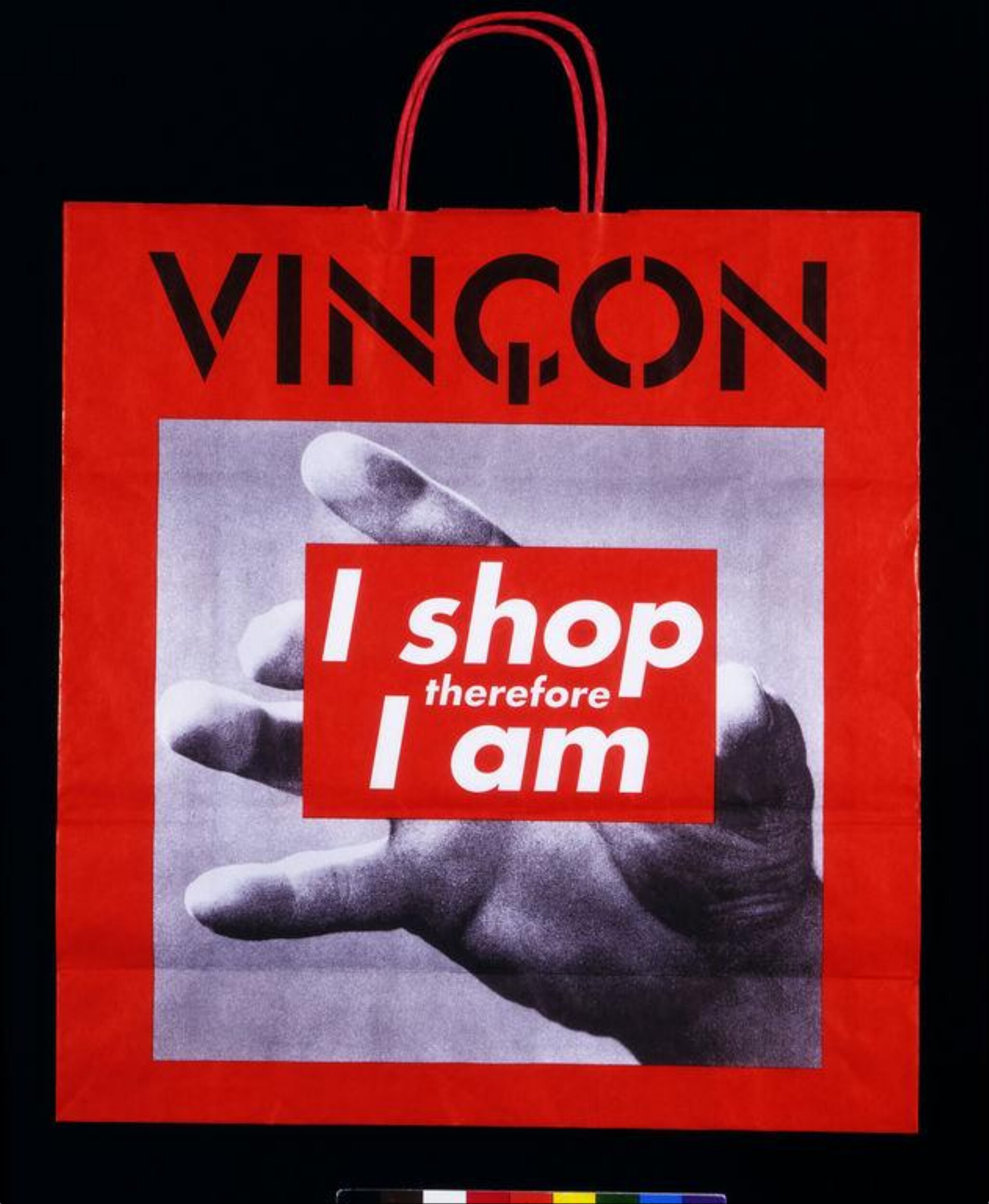

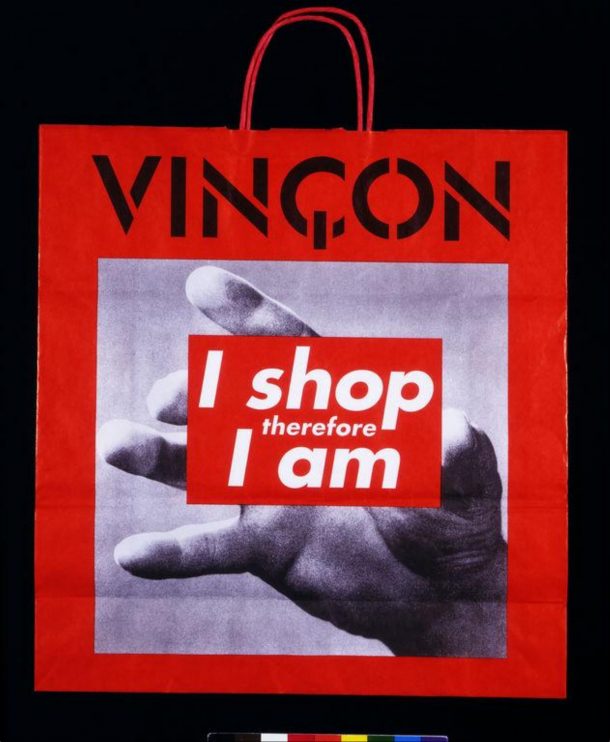

I shop therefore I am Carrier Bag, designed by Barbara Kruger, published by Vinçon department, Spain, ca. 1993 (E.2830-1995)

Further Reading:

‘Government refuse to rule out COVID passports for shops’ Aubrey Allegretti, The Guardian, 6 April 202.

‘Shoppers surge back to high streets as Covid lockdown eases in England’, Sarah Butler and Joanna Partridge, The Guardian, 12 Apr 2021.

‘What will the future UK high street look like?’, Natalie Theodosi, WWD, 5 January 2021.

‘BIG BIBA OPENS’, Kasia Charko, Kasia Charko, 28 June 2013.

‘London’s Lost Department Store of the Swinging Sixties, Inge Oosterhoff, MessyNessyChic, 7 July 2015.

‘Granny Takes A Trip, A Boutique Everyone Wanted To Be Seen’ Agnauta Couture, 16 December 2012.

‘The Many Lives of Vivienne Westwood’s Worlds End Shop’, Laura Hawkins, AnOther, 12 May 2016.