This guest post is written by Marina Giardinetti, an exchange student from Paris Diderot University who spent three months on the V&A/RCA History of Design programme, researching eighteenth-century design drawings and the role of women in the arts during that period.

One of the most well-known female artists of the eighteenth century, Mary Moser, began her career exhibiting at the Society of Arts (Fig. 1). For young girls it was a good springboard to reach the London artistic sphere. The Society of Arts was created in 1754 to encourage and promote knowledge on a wide range of subjects. It still exists today as the Royal Society of Arts, located behind the Strand. It held an annual exhibition, with prizes for different categories established to promote new designs for industry and to help create a wider diversity of goods. The ‘Polite Arts’ category encouraged young Londoners to submit their work, including drawings, models, engravings, and a very small number of prizes was specifically intended for young women, who were not invited to enter for the Fine Arts prizes. Instead, they were mainly encouraged to create drawings of patterns for embroidery, calico printing, porcelain and any design that could be categorized as ‘ornament’.

Some of these drawings are still held by the Royal Society of Arts and as an exchange student on the V&A/RCA History of Design programme I was able to spend time in London researching these designs in much greater depth and to understand the ways they might or might not have been used by craftsmen. Working alongside researchers interested in the same topics as me and having access to a wide range of resources helped me to develop and refine the subject of my dissertation. Moreover, workshops at the Royal College of Art allowed me to reflect on the notion of ‘design’ and essential methodological tools. The vast collections at the V&A sharpened my understanding of furniture, porcelains and textiles from the period.

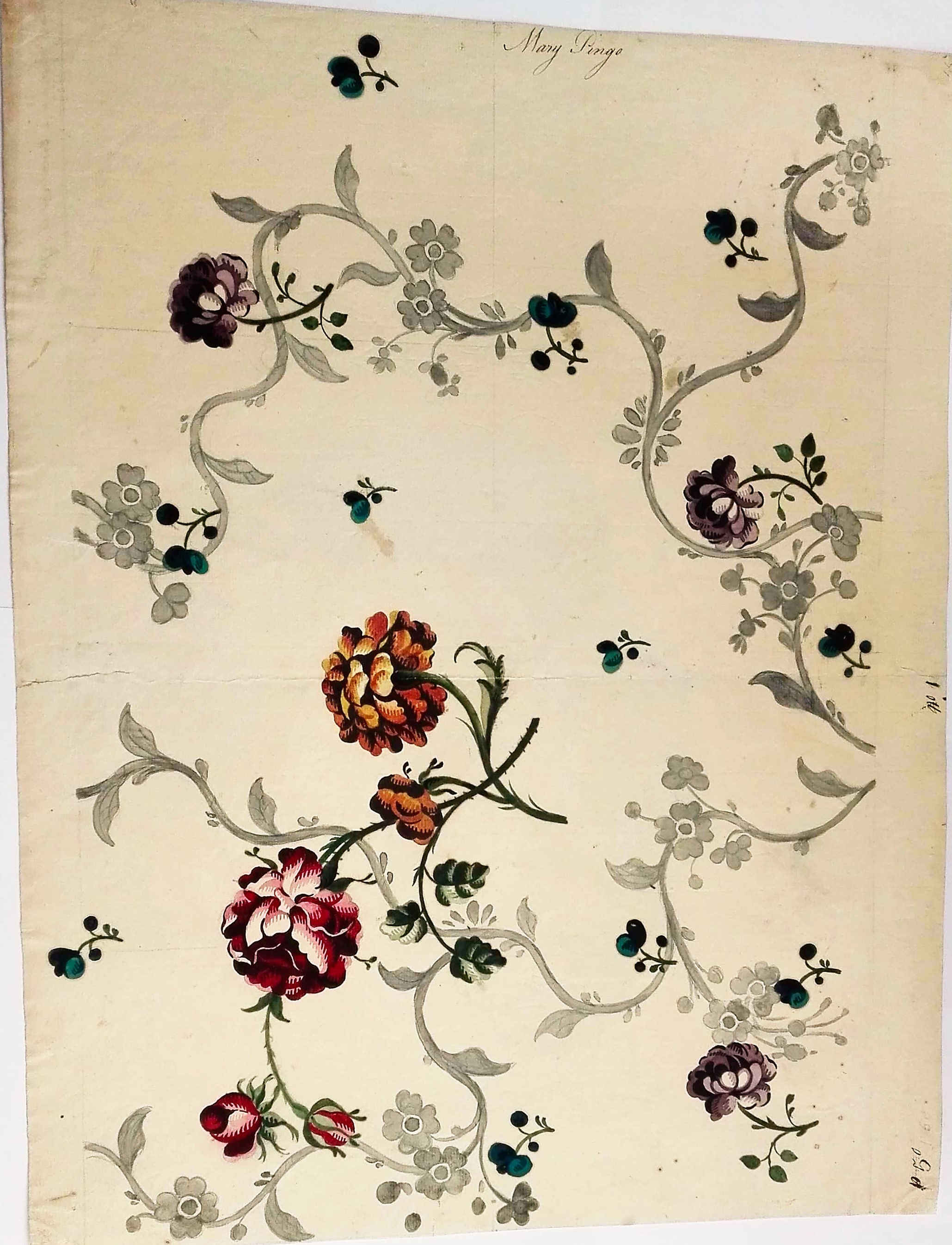

Having access to Anna Maria Garthwaite’s patterns for brocaded silks at the V&A (Fig. 2) helped me to contextualise a drawing submitted by Mary Pingo at the Society of Arts in 1758 (Fig. 3). The two drawings share many similarities, a reflection of the growing influences of fashion and the beginnings of eighteenth-century mass consumption. Thanks to this pencil and watercolour drawing, Mary Pingo won the second prize in the category reserved for women under eighteen. It could be fascinating to know if a design like this could have been technically used by a weaver; which would turn this unique piece of art into an industrial pattern. However, as this work is still housed in the Royal Society of Arts’ archives, it is unlikely it was used for any practical purposes.

We know that some entrants for the prizes were students of the drawing schools founded in London by famous artists and craftsmen. Printed drawing books were often used to teach the basics of drawing through copying. One example intended specifically for women was Jean Pillement’s The Ladies Amusement (London, c. 1762) (Fig. 4).

Given that women had limited access to drawing schools, they would have particularly relied on these books, something that is reflected in the subject matter of the designs submitted to the jury of the Society of Arts. The main themes used as models – flowers, birds, insects or little landscapes – could also be found in drawing books, which allowed women to develop their artistic talents by copying them. It is intriguing that young girls were asked to create original designs, by imitating printed books. They were not, however, taught the technical skills that would enable their designs to be transferred to different materials. From this perspective, their drawings can be understood more as inspirations, rather than effective models.

To see what else V&A/RCA History of Design students and alumni have been up to, take a look at our pages on the V&A and RCA websites.