The Karun Thakar Fund has awarded a Project Grant to scholar Caroline Sato in support of her project ‘Fashion: Kimono’. Here, Caroline introduces herself and her project.

Japanese clothing consumption rates escalated over the 20th century, and the rate of this escalation stimulated distinct changes in kimono style. While foreign fashions did impact Japanese kimono designs over this period, it is important to acknowledge that stylistic changes were not solely reflective of fashions emanating from other global centres. Changes also came from within, the result of indigenous aesthetic concepts as well as major events including earthquakes, war, and economic booms and recessions.

For example, according to the Japanese aesthetic concept of iki – which in fashion evokes a refined, understated elegance – the desirability of clothing may be found in a gorgeous lining, a rare pigment, the masterly weaving of unusual threads or a combination that goes against normal etiquette. Thus, a 1990s tsumugi homongi (woman’s semi-formal kimono of handspun raw silk) with a subtle tsujigahana (an intricate patterning technique that dates back to the 16th century) design might make a connoisseur gasp with delight while leaving others baffled over what makes a rough grey garment with a muted flower motif so special. Beyond a kimono’s fabric, the co-ordination and arrangement of accessories in consideration of the context it is worn in can be poetical. The late Shigeko Ikeda, a renowned collector, designer and stylist, displayed this concept brilliantly in her work curating kimono.

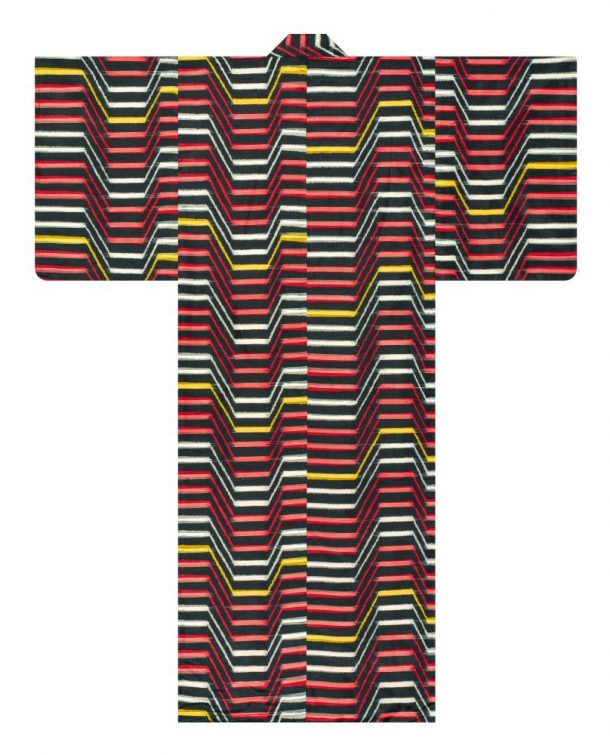

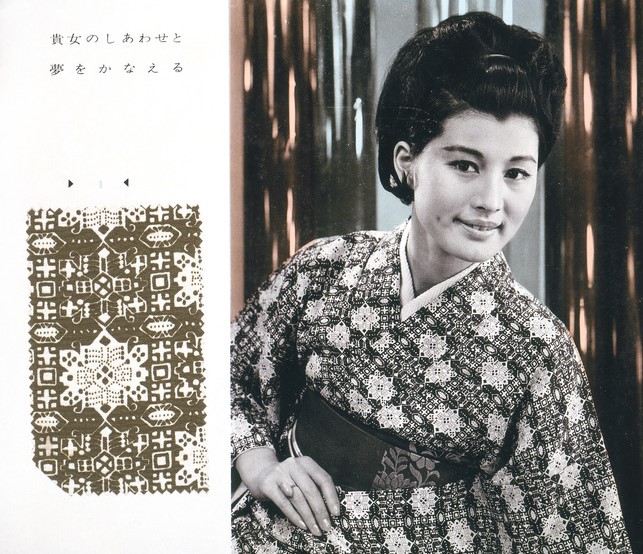

There is a good body of work tracing fashions in kimono from the late 19th to the mid-20th century, commonly summarised by a narrative that begins with the tiny stripes of Meiji-era (1868 – 1912) kimono; through to the widening stripes of the Taisho period (1912 – 1926); and on to the explosion of colourful graphic meisen on to the streets (kimono made of a less expensive, but more durable, silk stencil-patterned with bright chemical dyes). However, there is limited information in English about the post Second World War garments that are now such a feature of the second-hand market.

Conventional narratives of post-war Japanese fashion tend instead to focus on the crossover to western fashion and the decline of kimono. I don’t agree that kimono declined, however. As Mrs Ono (1899 – 1983), a second-hand dealer, reminisced in the 1980s, a time when the average parents could buy silk furisode for their daughters, ‘You know, I often think poor people today are as well dressed as the richest class when I was young’ (J. Saga, Memories of Silk and Straw: A Self-Portrait of Small-Town Japan. Tokyo 1990). Since 2020 the number of kimono on the second-hand market has reached unprecedented quantities. Many of these kimono are silk and wool pieces produced in the Showa period (1926 – 1989). And while kimono fashion still exists in Japan, the handmade, labour-intensive sector of the industry, which was strong until the 1970s, is now, by comparison, very limited. It is this sector of the industry which has declined.

Prompted by the limited information on 20th-century kimono, I am creating a book illustrating changing fashions over this period. My hope is that those who find such kimono in their hands through the second-hand market might develop a deeper understanding of the treasures they hold. I am very grateful to the Karun Thakar Fund for their support of this project.

The book will be comprised of two parts: a colouring section and a sticker section. The colouring section will feature illustrations of kimono fashions taken from 20th-century Japanese magazines. The second part of the book will consist of sticker illustrations of kimono owned by the women who have generously opened their drawers for this project. These stickers will be designed to be layered on to figures in underwear, like paper dolls. Featuring under-kimono, kimono, obi and perhaps haori (kimono jackets/outer layers), these stickers will include garments prepared for dowries, inherited or gifted, as well as ones bought for wear for cultural events such as the tea ceremony or for celebratory occasions.

The kimono illustrated will reflect distinct post-war trends. Silk kimono that were redyed and printed in the 1940s; the short Majolica omeshi boom of the 1950s with its woven metallic thread; and 1950s abstract designs in meisen, so beautifully represented in the Karan Thakar collection (see images below). Also represented will be the Michi boom after 1959; haori in both plain black and with colourful shibori (tie-dyed) patterns; and the popularity of wool until the mid-1970s. Homongi is a type of kimono that came into existence in the early 20th century, and along with formal garments (such as furisode and tomesode) served as the palette on which yūzen artists drew. Colours and motifs in yūzen further reflect different eras. Tsumugi (raw silk) developed in different colours and styles and is arguably what replaced the colourful and youthful meisen, being more iki in spirit and more appropriate for a wider age group; Edo komon, a classic small-scale stencil technique, had a revival; and finally, starting around the 1990s, tsujigahana, the yukata, and vintage boom were all kimono trends.

These are the kimono fashions that will be seen in the sticker book, and it will be up to the reader to step beyond simple colour coordination and make poetry in the dressing. I hope this book will enable children and adults alike to explore kimono with more nuanced understanding and will stimulate enquiring minds to delve deeper into this fascinating fashion world.