We love thinking about all kinds of material traces at the V&A – even those that might seem taboo, like writing, or even drawing, in books. Current History of Design MA student, Alicia Farrow, tackles a recent research paper by the V&A’s Head of Research, Professor Bill Sherman, which celebrates what might seem to be a disobedient practice. Librarians avert your gaze!

Would you ever draw or write on the pages of a good book? The next time you settle down with your favourite edition, would you consider having a pen or pencil in hand to scribble down your thoughts and ideas in the margins? Whether you deem such a practice abhorrent or exemplary, over the centuries many a reader has done it, as Bill Sherman revealed as part of the V&A/RCA History of Design Research Seminars.

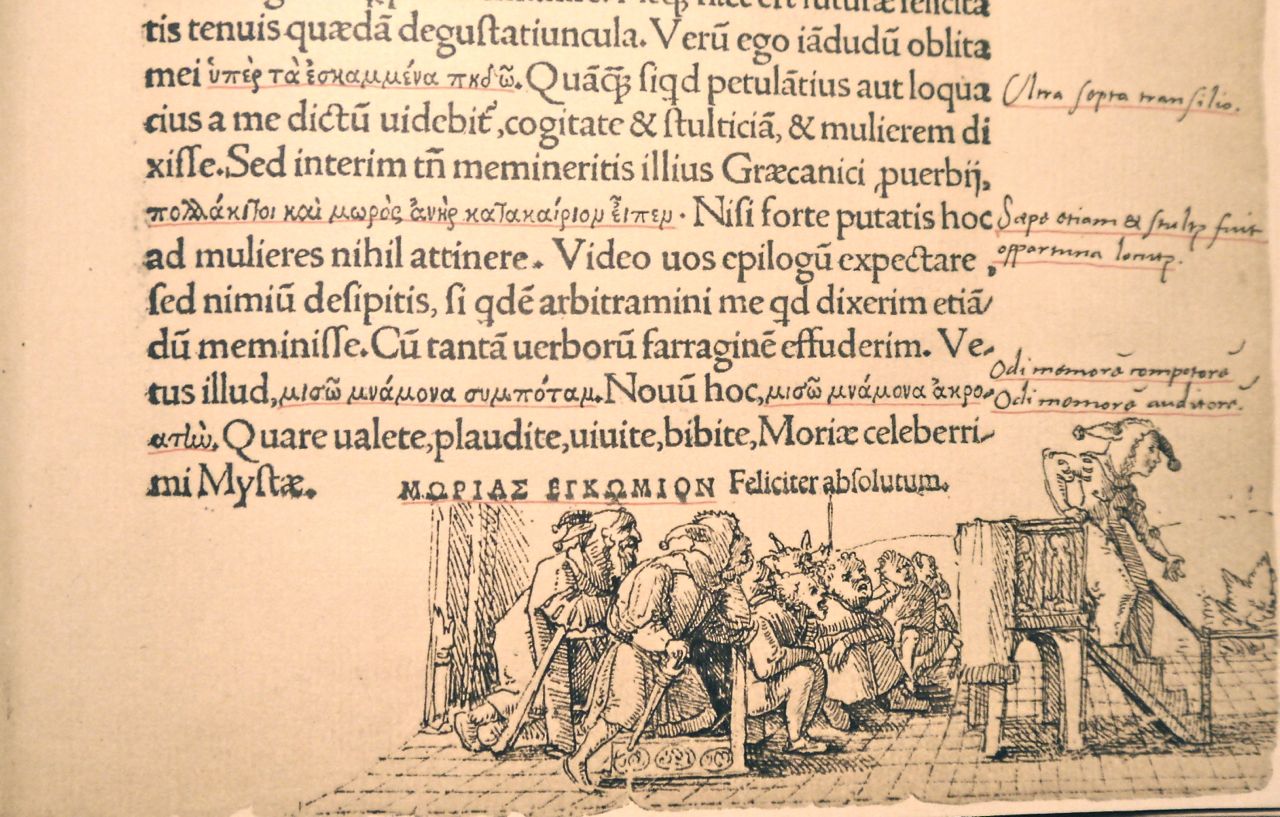

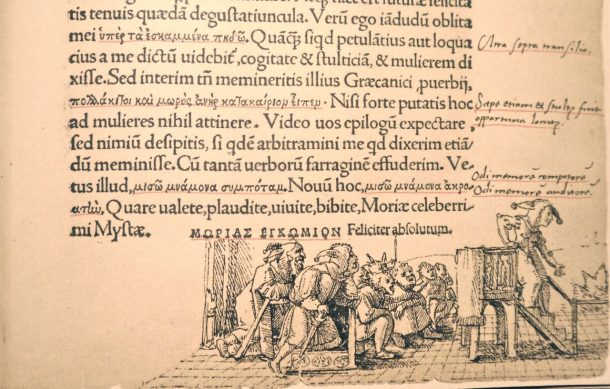

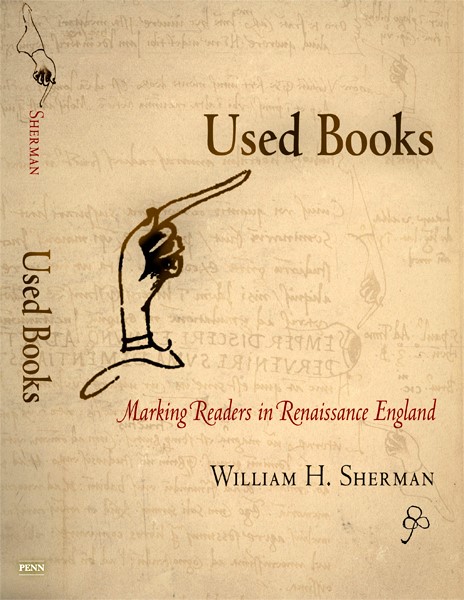

Sherman invited us on a journey back to the borderlands of the Renaissance to delve into a realm of drama, satire, and theatre, all played out in the margins of old books and manuscripts. He confessed to having become a marginalia addict back in his student days at Cambridge, a habit which in 2007 eventually led him to publish Used Books: Marking Readers in Renaissance England and to his current research project ‘The Reader’s Eye’ which explores the left-behind traces, marks and drawings of readers.

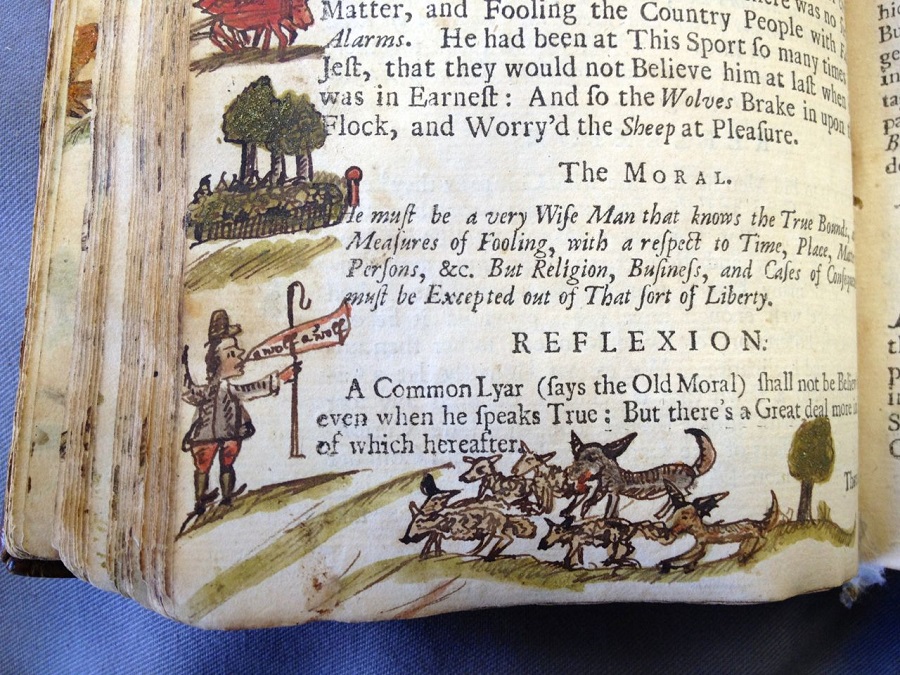

Sherman’s research follows a path from readers’ imaginations to their visual modes of response in the four long thin forgotten spaces on the edge of the page. Throughout Sherman’s paper, it was simple to see how he’d caught the bug; he brought the little-studied-but-fascinating world of Renaissance visual marginalia to life, as he examined the space where the seen, the drawn and the read reveal their essential bond. In making these links, Sherman is drawn to the margins as a deeply divisive subject, not only between those that either hold it in contempt or esteem, but also as an area of scholarship that destabilises our understanding of the relationship between word and image.

With a playful smile, he wished that his legacy could be to finally get the word ‘manicule’ into the Oxford English Dictionary. A word, or rather an image, he has had the pleasure to often stumble across as he explores these fringes: ‘manicule’ derives from the Latin root of ‘manus’ for ‘hand’ and ‘manicula’ for ‘little hand’ and refers to little illustrated hands that protrude from the reader’s imagination and into the body of the text. Manicules, argued Sherman in Used Books, hold the key to restoring the humble hand to its rightful, active place in reading.

![3.Father and Son. [Left] Hans Memling, Portrait of a Man with a Roman Medal (Bernardo Bembo?), oil on panel, ca.1480, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp; [Right] Titian, Pietro Bembo, oil on canvas, ca.1540, National Gallery of Art, Washington](https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/3.-Bembo_5ae9d425f6d65f2225a2ac3eb84ec651-610x389.jpg)

In his current research Sherman has returned to the visual and has begun to see another common marginal image. ‘Opticules’, which are small, abstract eyes peering into the text from the periphery, the reader’s eye. Together the idiosyncratic manicules and opticules seem to embody the ghost of a past reader and the visual offerings provide an insight into what kind of imagination was at work.

From ancient storytellers, poets and philosophers, to Renaissance architects, artists and printmakers, Sherman fluidly draws on the ideas of a rich and diverse cohort, including Aristotle, Aesop, Dante, Inigo Jones, Michelangelo, Shakespeare, Holbein and particularly Erasmus, to illustrate an elegant point. He suggests a healthy entanglement of word and image augments the truest understanding of ideas by activating the imagination.

Notably, it is only children today that still experience a more natural interweaving of text and image in illustrated storybooks. Building on W.J.T. Mitchell’s notion of imagetext, Sherman goes further to propose that through old books we might begin to rethink interdisciplinarity and mixed media as a pre-modern rather than post-modern conception.

It is fruitless to ask you, the reader, to take up pen or pencil as you read this blog post – the digital interface regrettably cannot yet allow for a Renaissance approach to reader interaction. However the digital platform does at least tolerate feedback, so you are encouraged to writedraw your comments below the line.

***

To see what else V&A/RCA History of Design students have been up to, read our other blog posts, check out our pages on the RCA website and take a look at Un-Making Things, the student-run online platform for all things design history and material culture. You can also come meet some of us in person at the current series of V&A/IHR Early Modern Material Cultures Seminars, which have just started again at the Institute of Historical Research in London.