The Art of Electro-metallurgy

The pioneering British electroplating company, Elkington & Co., was the world’s pre-eminent art-metalwork manufacturer of the 19th century. Founded by cousins, George Richards Elkington and Henry Elkington, and financed by the steel pen magnate Josiah Mason, from 1836 the company invented, patented and developed the key elements of the art of electro-metallurgy.

Elkington & Co. were the first people to harness the power of electricity for the creation of artworks and consumer goods. They used electro-deposition to ‘grow’ highly detailed and ornamented objects particle by particle in a mould. Elkington’s art of electro-metallurgy was a 19th century industrial alchemy, which sparked the electrical revolution that founded the modern technological world.

The quality and quantity of the company’s industrial art manufactures was truly spectacular. They produced award-winning showpieces for the International Exhibitions; major sports trophies, like the Wimbledon singles trophies for men and women; testimonials for ’eminent Victorians’; ‘electro cast’ sculptures for major public art commissions, like the Palace of Westminster, and electrotype ‘facsimiles’ of historical objects that laid the foundation and still grace most of the world’s great museum collections. Elkington’s electroplated flatware and hollowware furnished steamships and trains, fine restaurants and grand hotels, and were conspicuously displayed on the sideboards and dining tables of fashionable middle class homes all over the world.

Critically and publicly acclaimed at the Great Exhibition of 1851, Elkington & Co. became one of the world’s first multinational brand identities and luxury trademarks. It was the only British company to consistently win the highest awards at all seven of the International Exhibitions held from 1851-1878. The history of Elkington’s achievements is the great, untold British success story of the Victorian era.

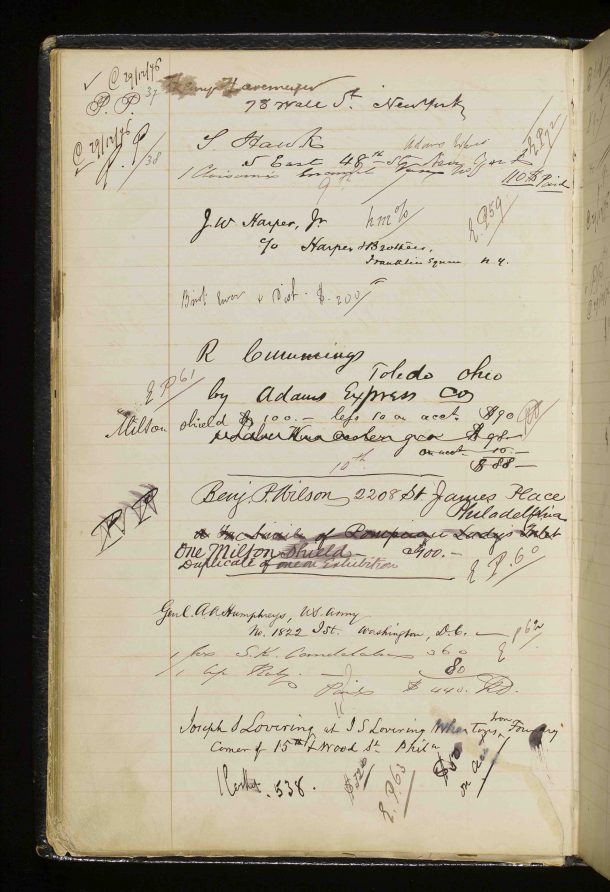

The Elkington & Co. Visitors’ Book, 1855-1878

From 1855-1878, Elkington & Co. used a black leather bound visitors’ book to record the signatures of the many eminent people that visited their acclaimed display stands at four different International Exhibitions:

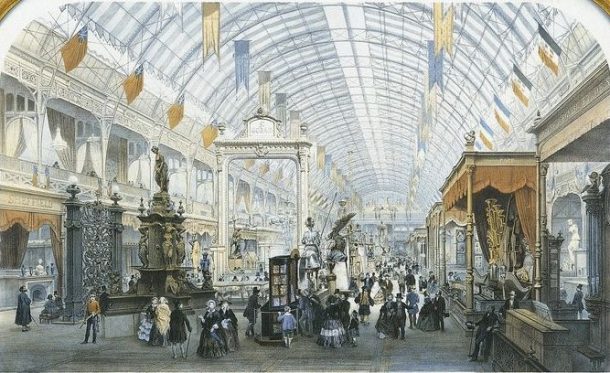

- The 1855 Exposition Universelle in Paris took place on the Champs-Élysées from 15 May to 15 November 1855. Its official title was the Exposition Universelle des produits de l’Agriculture, de l’Industrie et des Beaux-Arts de Paris 1855. Held at the height of the Crimean War, the spectacle was the Second French Empire ‘s attempt to surpass London’s Great Exhibition of 1851, and export the fête impériale of the Bonapartist regime founded by Napoleon III in 1852.

- The 1873 Weltausstellung in Vienna, the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, took place from 1 May to 31 October 1873. The Second French Empire had ended two years earlier in May 1871, with defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, and a week after the Weltausstellung opened, the Vienna Stock Exchange crashed on 9 May 1873, prompting a global depression that lasted until the end of the 1870s. Nevertheless, the exposition hastened the Ringstraßenstil architectural regeneration of old Vienna into a great Imperial showcase for the Dual Monarchy.

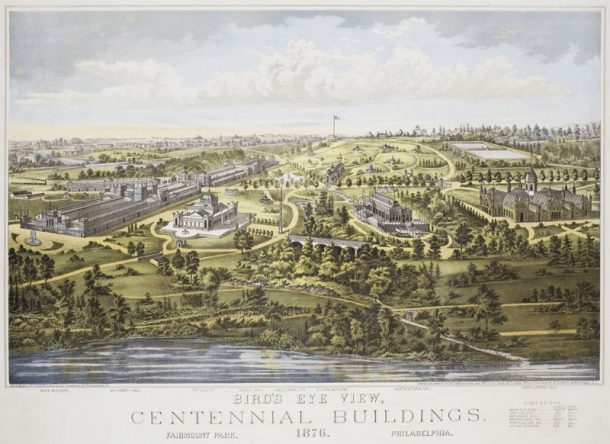

- The 1876 Centennial International Exhibition in Philadelphia was held to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, and was the first official World’s Fair in the United States. It took place from 10th May to 10th November 1876, a decade after the Civil War, and the exposition heralded the end of the Reconstruction Era (1863–1877) and marked the beginning of the industrial and economic supremacy of the USA during an era, which, three years earlier, Mark Twain satirically labelled ‘The Gilded Age.

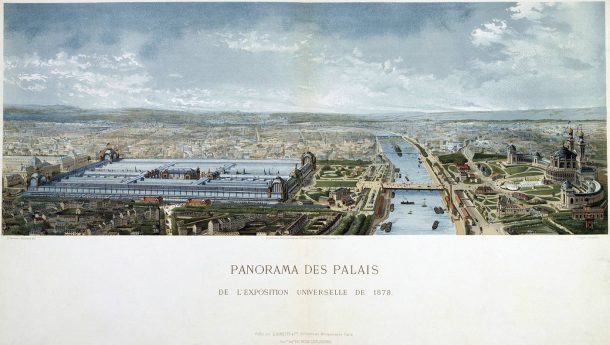

- The 1878 Exposition Universelle in Paris was the third one held in France, but was on a far larger scale than all the previous International Exhibitions. It patriotically announced the revival of France after the reparations and revanchism that followed the Franco-Prussian War. French exhibitors contributed half of the displays at the 66-acre site in the Champ de Mars. More than half a million tourists visited Paris, adding to over 13 million visitors between 1st May to 10th November 1878, making the spectacle a huge financial success for the French Third Republic.

A Global Who’s Who of the mid-19th Century

The register of around 600 signatures recorded in the manuscript is a global Who’s Who. It provides a biographical portrait gallery of the age, which reflects the social and cultural characteristics of each successive International Exhibition, and maps the changing economic and political context of the mid-19th century.

Over the next few months, this blog will share a few of the fascinating stories as they emerge from my transcription of the handwritten manuscript and research into the lives behind the signatures and art historical journeys of the objects recorded in the Elkington & Co. Visitors’ Book, 1855-1878.

The Elkington & Co. Visitors’ Book Digitisation Project is an AHRC-funded collaborative research project run by the Sculpture, Metalwork, Ceramics and Glass Department, with the support of VARI, Word & Image Department (Digital Collections & Services and Designs & Archives), National Art Library and Digital Media Department.

Is this the same company that fitted French movements to it’s clock cases?

If so who made the clock movements?

Many searches I made mention Elkington and co, Paris, however no more than that. Perhaps it is the way I am searching, not sure. Any help would be appreciated.

I am trying to learn aboutan Elkington plaster shield ? Achilles by Cellini, #3015. A photo similar/the same as the one I have resides in the Powerhouse museum in Australia. An architectural historian professor suggested these were made and sold as “decoratives art” pieces during art expositions at the turn of the last century. Any ideas or leads will be appreciated. Thank you. D Willis

Dear Deborah, please can you send me a few photographs of your Elkington plaster shield to metalwork@vam.ac.uk and tell me all you know about it so I can identify it and provide you with historical information. Elkington were a metalwork company and usually made electrotype copies of art historical artworks and objects rather than plaster, which makes yours rather interesting. The V&A/Lund Humphries are about to publish a new book that I have co-authored with Angus Patterson (senior curator) called The Museum and the Factory, which you will find informative and interesting about the artworks and objects made by Elkington for the Museum and the international exhibitions in the 19th century: https://www.lundhumphries.com/products/106982

I have a similar Briot Ewer but with different figures and two sections of the body oxidised with copper green not deposited silver. It has no silver panels and the figure on the handle is positioned differently . If I had an email address I could send a picture.

Sear Alistair Grant,

I have an ink stand which I believe may be made by Elkingtons.

Family history has it that it was a gift from Florence Nightingale to a family ancestor. There was a letter of provenance but that has sadly been lost. I remember it being

there, rolled up inside during the 1970’s.

It may be a long shot but is there any mention of Florence buying such an item?

Thank you and kind regards

Hamish