By Livia Rezende, Tutor in History of Design, Victoria and Albert Museum / Royal College of Art

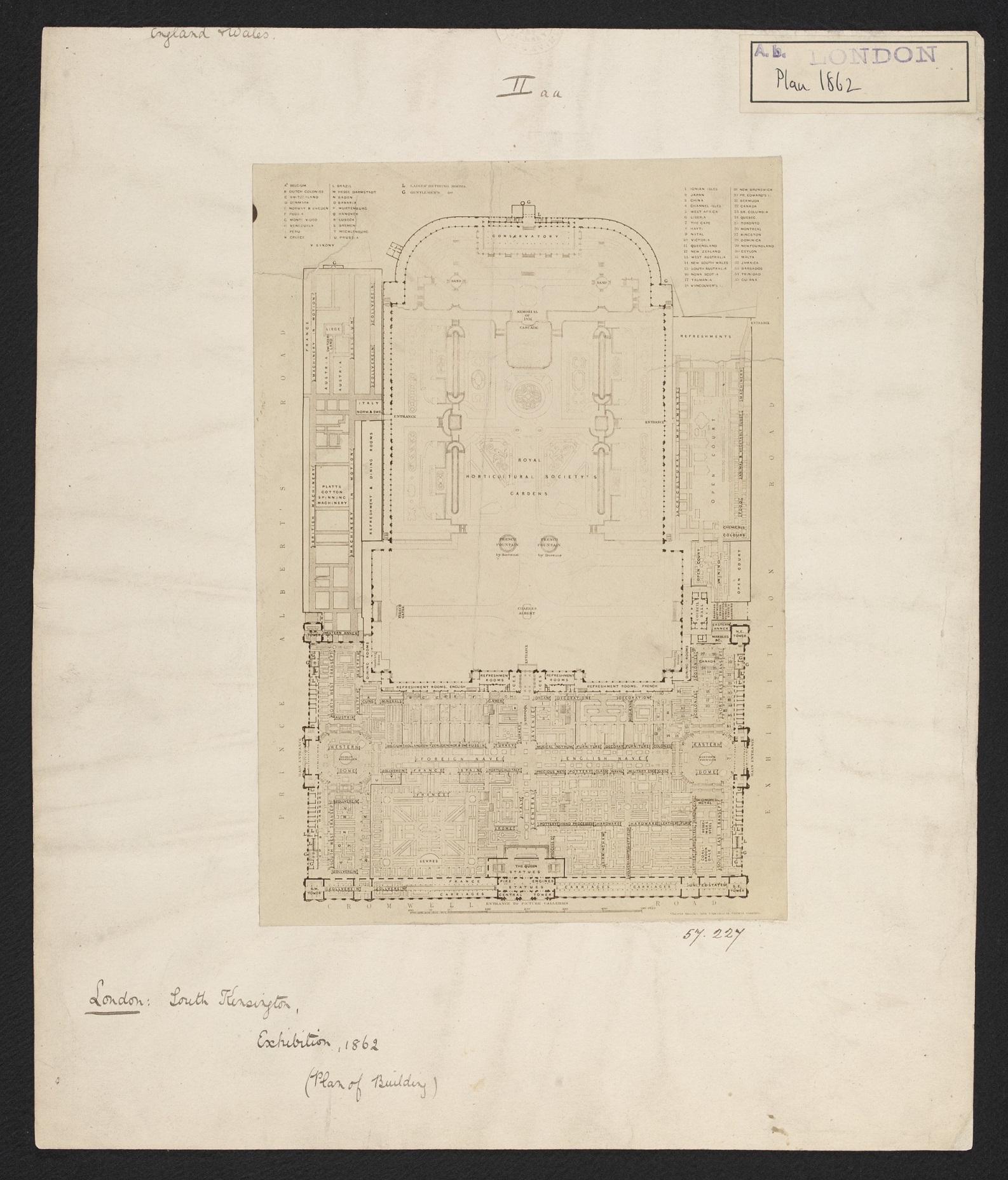

Brazilians have been coming to South Kensington to show and debate art and design since at least 1862. For the International Exhibition taking place that year at the Royal Horticultural Society (today the Natural History and the Science Museums), a Brazilian committee brought more than 600 items to London, from photographic portraits and oil paintings to textiles and leather goods.

This show was the first of many. Over the decades, Brazil has frequently promoted abroad its creativity, materials and processes of making. 152 years later the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), an institution whose genesis is also in debt to the nineteenth-century craze for exhibitions, teamed up with the Embassy of Brazil in London to show and debate, once more, Brazilian art, architecture and design in South Kensington.

What makes this opportunity different from its precursors?

In the first decades of the twenty-first century, Brazil has become big news abroad. International commentators have hailed the country and its recent economic and political achievements as ‘Latin America’s big success story’.[1] With the economic boom comes new challenges and demands for strategic positioning. But in contrast to previous times, when a projection of the nation was sent abroad for promotion, this time around international eyes have turned towards Brazil, and its status as a democratic, modern, and progressing nation is being closely scrutinised.

The ‘Brazilian Contemporary’ event was the V&A’s and the Embassy of Brazil’s response to the pressing question of actualising abroad what is happening within the country. Until recently, one of the few Brazilian objects held in the V&A’s collection was a feather fan made by the Natté sisters in Rio de Janeiro’s Ouvidor Street, a sophisticated hub for craft production and the high-life during the second half of the nineteenth century.

Brazilian feather fans shot to international fame in the 1870s due to their exotic qualities and popularisation in the International Exhibitions and World’s Fairs of its time. Because of the ‘Brazilian Contemporary’ event, the V&A was also able to update its collection of Brazilian artefacts. Collector Raul Schmidt Felippe Jr. was in town for the opening of the exhibition ‘Brazilian Design: Modern & Contemporary Furniture’ (27 March to 9 May) held at the Brazilian Embassy, where 45 of his modernist and contemporary pieces were displayed. Having attended the Museum’s roundtable, Felippe generously donated to the V&A one of the most emblematic pieces of Brazilian mid-century furniture design, an armchair by Joaquim Tenreiro.

The event itself took the format of a roundtable discussion organised by the Museum’s Research Department, coordinated by Cher Potter (London College of Fashion/V&A Research Fellow in Futures/Design) and generously sponsored by the Embassy. Over the afternoon of the 21st of March, practitioners, writers, academics and curators working in between Brazil and Britain addressed questions of identity and internationalisation in times of unprecedented economic growth and social change.

The first round of debate centred on contemporary Brazilian design and architecture. Being the design historian in the room, I began the conversation by reminding the audience how national myths can be constructed, embodied in designed objects and disseminated to convey an idealised image of a place. The aim of my talk was to complicate the current discourse. Going beyond a simplistic celebration of creativity and natural beauty and bounty, I questioned the very assumption that there is a design that is specifically Brazilian. What is Brazilian design: is it a design made in Brazil, a design from Brazil and/or a design for Brazil? By presenting and discussing a series of objects, design projects and ideas made in, from and for Brazil, I placed on the ‘roundtable’ issues of design deterritorialisation, social inequality and class divide, and the everyday experience of Brazilians dealing with dysfunctional services, products and infrastructural breakdowns.

As if arranged to perfectly segue my provocations, Gisela Domschke followed with a timely response to what a design for Brazil might be like. Designer, media artist and independent curator, Domschke discussed her project called Labmovel, a mobile lab platform that takes art and knowledge exchange to youngsters in impoverished areas of the city of São Paulo. Domschke’s talk centred on design and media art as actors of social change – or exchange, to be more precise – since Labmovel offers activities and workshops in public spaces. Design for Brazil according to Domschke is, a design that is less interested in moving products off the shelves than in developing methodologies and processes of creation, circulation, disposal, use and consumption more fitted to the social, cultural and economic contexts of Brazil today.

Architect, researcher, essayist and provocateur Carlos Teixeira followed suit picking up on issues of planning (as architecture and design do) in a city (Belo Horizonte) in a country (Brazil) where planning is not always prioritised (football tactics either). Carlos, co-founder of Studio Vazio S/A, discussed a typical dwelling from Belo Horizonte built on stilts and an excess of structural elements to question urban informality, lack of planning and the theatrical use of urban voids as a strategy to turn an idle space into spectacle. At the ‘Brazilian Contemporary’ event, Teixeira also proposed the ‘occupation’ of Belo Horizonte’s Arrudas River with a landscape/architectural intervention that reclaims the river back to life and the city.

The internationalisation rather than the territorialisation of Brazilian art, and of art in general, was the core theme of the event’s second round of debate. Introduced and chaired by Kiki Mazzucchelli, an independent curator and writer working between London and São Paulo, this round centred on post-war Brazilian art and exhibitions. Mazzucchelli brought to the audience’s attention the longevity and rude health of Brazilian art and of its relevance abroad. At least since the mid-1960s, Brazilian artists have been working and exhibiting in places like the Signals Gallery in London or being promoted by curators like Guy Brett and institutions like Tate Modern in ways that placed them not so much as ‘Brazilians’ but mainly as artists who pushed the boundaries of art rather than that of a territory.

The argument of decentralisation was also central to Jochen Volz’s presentation of the Instituto Inhotim, Brazil’s biggest privately owned art institute that prides itself on site-specific, large-scale works of art. Volz is currently Head of Programmes at the Serpentine Gallery but he talked about his previous role as Inhotim’s Artistic Director assembling complex artworks like Cris Burden’s Beam Drop or curating pavilions to house traces of Tunga’s performances. Inhotim, although located in Brazil, is not promoting an art that is overtly Brazilian but is continuously (and strategically) placing it at a par with art made anywhere around the globe.

The third and last speaker of the day, Alexandre da Cunha, reinforced the conversation on a ‘Brazilian Contemporary’ not specifically located in Brazil. Cunha graduated from London art schools and has been working and exhibiting in the city for over ten years. Yet, some of Cunha’s interests reflect his cultural background as seen in MIX (2012), a permanent work devised for a public space in London made of reclaimed concrete mixer drum placed on a concrete plinth surrounded by concrete building developments. Concrete is also a material long associated with Brazil (see São Paulo’s concrete jungle, or Brasilia’s concrete modernism). Playing with materials and forms, Cunha’s work displaces our familiarity with objects, surfaces and ideas.

As a strategy, we conclude, displacement is key to help us actualise the debate on the ‘Brazilian Contemporary’ in art, architecture and design and with great initiatives like the ‘Brazilian Contemporary’ event so to, we hope, come further great outcomes.

Look out for the Brazilian Contemporary Roundtable Series starting next week. This will be a series of seven videos taken of each speaker at the event that was held on the 21st March 2014 at the V&A.

[1] ‘Brazil Takes Off: A 14-Page Special Report on Latin America’s Big Success Story’, The Economist, 14-20 Nov 2009, (13 and 1-18 – special report), p.13.