A burkini and refugee flag are the two latest acquisitions by the Museum’s Design, Architecture and Digital department, recently installed in the Rapid Response Collecting gallery.

Text by Mariana Pestana, Curator of Future Design, and Kristian Volsing, Research Curator – Videogames

The refugee flag was commissioned by the Refugee Nation, a not-for-profit creative project led by Artur Lipori and Caro Rebello in collaboration with a group of refugees, with the support of Amnesty International, FilmAid, Makers Unite and U-able. The aim of the Refugee Nation project is to create a symbolic nation to represent the millions of displaced people worldwide, and its inception was motivated by a desire to support the first refugee team competing at the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

The striking orange flag is cut horizontally by a black line representing the ambiguous situation of refugees today: at once crossing over borders and negotiating life within strict geographical limits. The flag was conceived by artist Yara Said and its design refers to the lifejackets worn by many fleeing conflict. Said is herself a refugee who studied at the Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Damascus before being forced to leave her country to find asylum in The Netherlands. “The lifejacket is a symbol of solidarity for all those who crossed the sea in search of a new country,” says Said: “I myself wore one, which is why I so identify with these colours.[1]”

Despite the flag being created to support refugees competing in Rio, the International Olympic Committee did not permit the refugee team to carry the Refugee Nation flag as it does not represent an official Olympic federation. This did not stop spectators and fellow athletes all over the world – from Engenhao Olympic Stadium or Portela, one of the biggest Samba Schools in Brazil, to Ottawa in Canada or a refugee camp that hosts around 185,000 people, including three athletes of the refugee team in Kakumo, Kenya – from displaying the flag during the Games in acts of unity, and on 14 August 2016 the flag was presented as part of an official ceremony at the men’s hockey quarter final between India and Belgium. The flag is an example of the power of design to claim both a symbolic and a physical space for the recognition of refugees and their plight.

In addition to the flag, the Refugee Nation commissioned an anthem, composed by Syrian refugee Moutaz Arian who now resides in Istanbul. Previously a music scholar at the University of Damascus, Arian decided to create an anthem without words so it would resonate beyond borders. Music is often described as a universal language, as Arian says: “Music is the best language to deliver my message to humanity, which is to love each other, and this language does not require a translation.[2]”

The flag and anthem drew global attention to the current refugee crisis. By creating material symbols to represent an imaginary nation, these design objects force us to reconsider the stateless condition of 36 million people. In borrowing the official language of nation building, they highlight the global significance of the refugee question.

Seen alongside the Refugee team at the 2016 Rio Olympics were an increasing number of Muslim women competing in sportswear with hijab. Yet this same summer also saw women on French beaches being fined for wearing, and being forced to remove, similar attire.

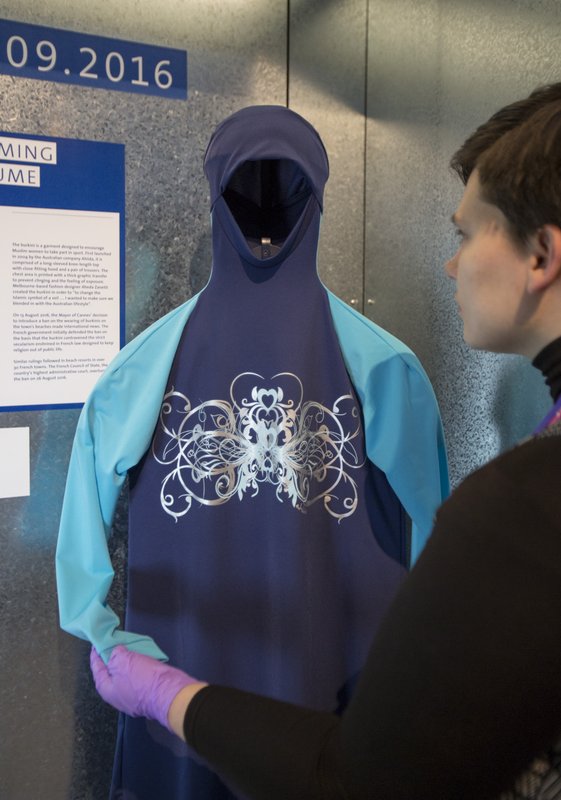

The Burqini by Australian designer Ahida Zanetti launched in 2004 as a way for Muslim women wanting to dress modestly to be able to participate in sport. Zanetti was inspired to design the garment after seeing her niece struggle to play school netball wearing a hijab and a long-sleeved, high-necked top. The burkini is made up of a knee-length, loose-fitting top, with long sleeves and an attached close-fitting hood and trousers with ribbons to attach to the inside of the top. A wide and dense graphic transfer is printed across the chest area to stop the garment clinging and preventing a feeling of exposure. The garment first drew attention when Zanetti was approached to produce a burkini for an advertising campaign for the charity Surf Life Saving aiming to help Muslims integrate into Australian culture. Initially there was difficulty in finding female Muslim lifeguards due to the beachwear standards, so Zanetti created a burkini in the association’s uniform colours. Since then, her Burqini brand has sold over 700,000 pieces worldwide.

Twelve years later, this positive act to encourage women into sports suddenly became a symbol of the fragile national identity politics of a country on the other side of the world. This renewed focus reflects wider contemporary debates around identity and immigration at the political forefront of Europe. Following a year in which Islamic extremists targeted France with several major terrorist attacks, around 30 major coastal towns tried to ban the burkini from being worn on their beaches. Corsica in particular experienced violent clashes between youths and Muslim families over the matter.

The French government initially defended these bans because they were considered to be in keeping with the strict secularism enshrined in law and designed to keep religion out of public life. It’s a law that led to the banning of conspicuous religious dress in state schools (headscarves, but also crucifixes and the kippah), and to the niqab being banned in all public places in 2010. Arguing that women should be forced to bare more of their body against their wishes is problematic and France’s highest court, the Conseil d’Etat, ruled against a nationwide ban on 26 August 2016, even though individual town mayors still sought to enforce it.

Zanetti’s original burkini design has now been copied worldwide and mass-produced here in the UK by companies such as Marks and Spencer and Sports Direct, demonstrating how these retailers are reacting to changing demographics in Europe.

A space to display design that speaks of wider social or political contemporary events, Rapid Response is a cross-disciplinary collection that deals with everyday artefacts made and used in our global society, exploring the politics inherent in manufactured objects. This approach to collecting searches for the evidence of important events – from technological developments to protests, disasters or censorship – through designed objects.

It is extremely challenging to discuss the mass displacement of people, and the refugee and identity crises, in the context of a museum: no single object can hold up to the task of representing the scale or breadth of such decisive moments in contemporary history. Yet in collecting and displaying these items in the context of Rapid Response, we seek to focus attention and debate around designed objects, encouraging visitors to critically assess their interplay with significant social and political events.

[1] The Refugee Nation, The Refugee Nation – Official Video, 2016 <http:// https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dkby9BmYrXQ > [accessed 28 November 2016]

[2] The Refugee Nation, The Refugee Nation – Official Video, 2016 <http:// https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dkby9BmYrXQ > [accessed 28 November 2016]