By Frankie Alves, Archivist, Design Archives Online

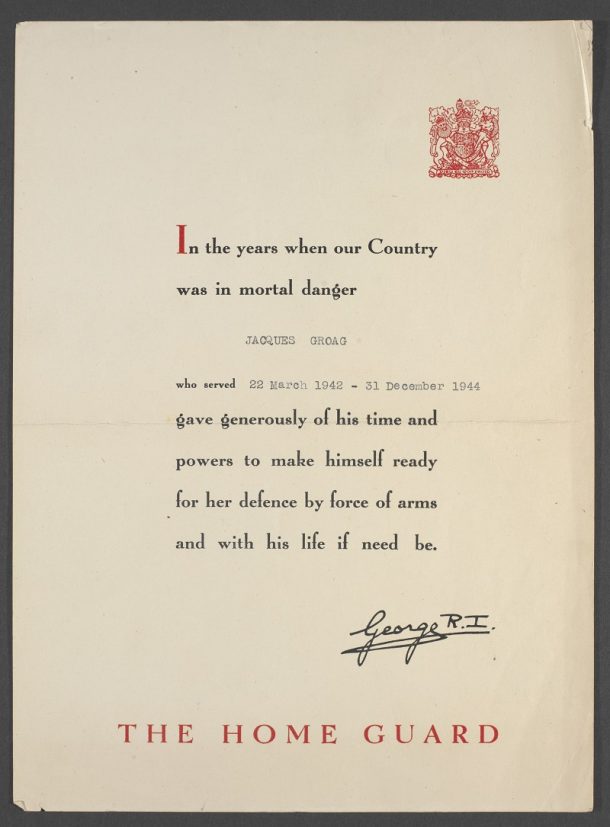

One of the main tasks of the Design Archives Online project is auditing, which, broadly speaking, means checking that everything in a particular archive is where it’s supposed to be, and that the catalogue description is accurate – and is a great way of getting to know collections that I haven’t been cataloguing. Most recently I’ve been auditing the archive of architect and furniture designer Jacques Groag and his wife, textile designer Jacqueline, and a few days ago, I came across this:

Born in what is now the Czech Republic, both Jacques and Jacqueline spent much of their early careers in Vienna, before leaving for UK in 1939. To gain British citizenship, Jacques was required to undertake a form of national service and so, being around 50 years old, he volunteered to be a member of “Dad’s Army” – the Home Guard.

Many of our Jewish émigré designers also made some contribution to Britain’s war effort, albeit in a more ‘arty’ manner. Hans Schleger’s archive, which has been featured in this blog before, is full of examples of Second World War posters and advertisements for various government agencies.

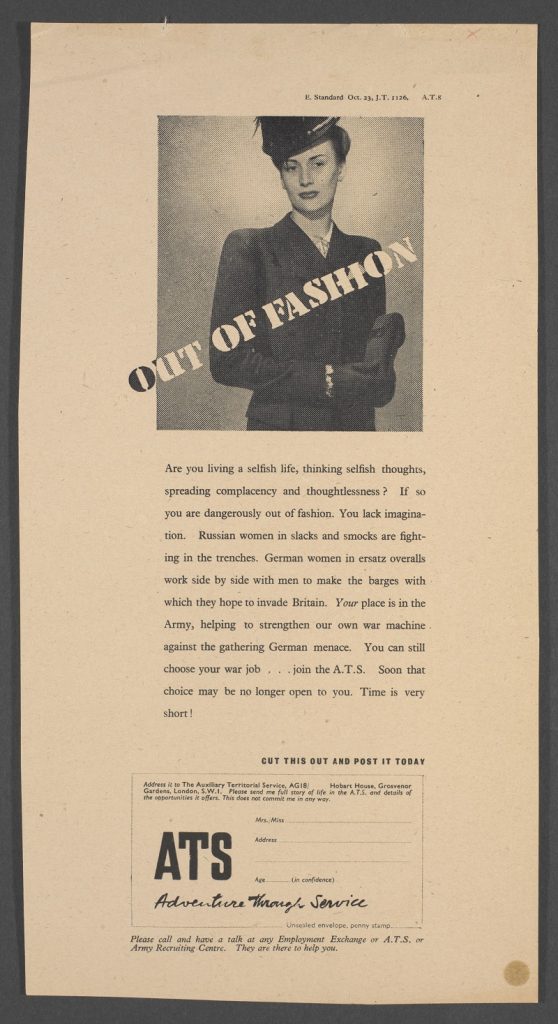

Schleger had been living in Germany when the Nazis came to power and he had heard Goebbels speak – he was very aware of the power of propaganda, and in particular of how the tone and wording of an advertisement could influence its audience.

Formed in 1938, the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) was the women’s branch of the British Army and eventually counted such figures as Churchill’s youngest daughter Mary and the then Princess Elizabeth among its members, but according to Mary Gowing, whose copy accompanied Schleger’s designs in the recruitment campaign, the ATS’s reputation had gone downhill in the year following its foundation, and was in need of a facelift. Schleger kept the notes he made explaining how he wanted to approach the problem, which included designing the advertisements to make a lasting impression, not getting carried away with flowery language and – crucially – appealing directly to consciences of the women they wanted to recruit. What is more, Schleger was convinced of the power of persuasion over telling people they had no choice:

Dull information of sergeant-major tactics will not achieve anything, since there is no compulsion to obey and people will resent being bullied. To mould the mind successfully, one needs diplomacy and persuasion of their interests and psychology.

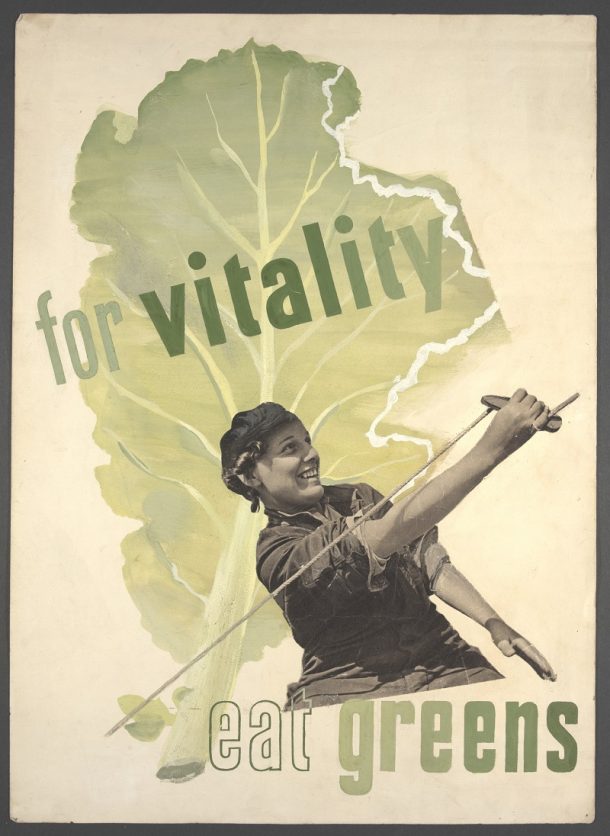

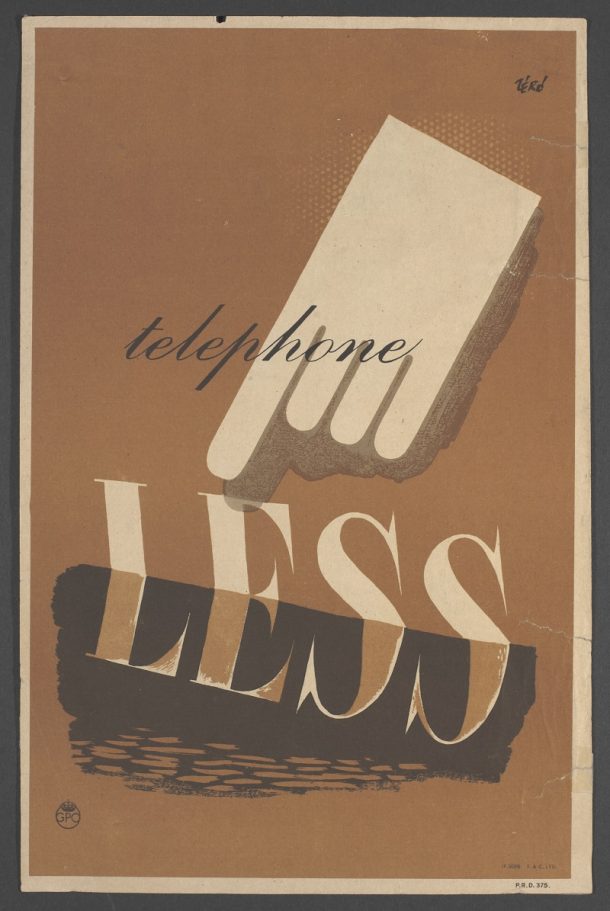

This was something that Schleger put into practice in his other Second World War work, using gentle, positive persuasion alongside his striking, modernist artwork to persuade the general public to do their bit for the war effort, whether by taking the pressure off the over-stretched General Post Office telephone exchanges by making fewer phone calls…

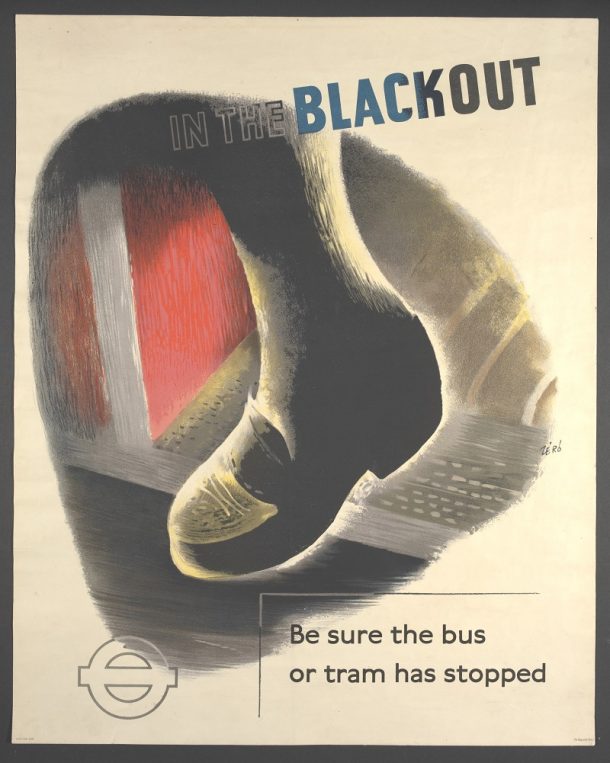

By preventing avoidable accidents when taking public transport in the blackout…

And as well as refraining from making unnecessary phone calls and getting hit by buses after dark, you should be sure to eat your home grown, off-ration greens!