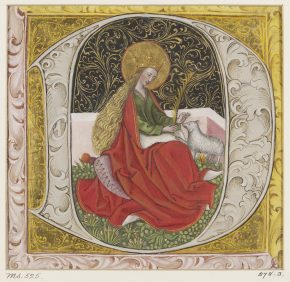

Sometimes, when looking through medieval manuscripts, it seems that everyone is wearing a halo – page after page of holy families, saints and virgin martyrs! This beautiful image of Saint Agnes (with her lamb) has beautiful flowing hair, a shimmering halo, and a heavenly crown.

But a mere mortal woman could not copy this look. Female saints (and young unmarried girls) could get away with loose flowing locks, but for almost the entire Middle Ages adult women would not show their hair at all in public. This reflected the teachings of St Paul and early church fathers such as Jerome and Augustine that women should cover her head as a sign of modesty.

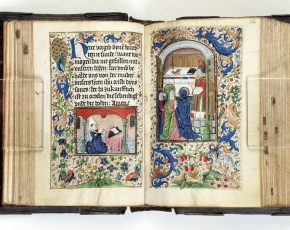

As you can see in this calendar page, women from lower classes generally wore hoods or wimples but a fashionable medieval woman could cover her head and still look show-stopping. Surviving examples of clothing and accessories are rare from the middle ages so we have to look for evidence in other places – and if you look carefully at manuscripts (past the legions of saintly women to background characters or images of owners), there is evidence of the amazing headwear fashions displayed by the medieval lady.

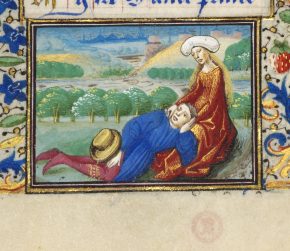

Here we can see a common fashion from the 13th and 14th centuries where hair would be plaited and contained in a net. Sometimes, as in this example, a chin band (barbette) would pass under the chin, and the look would be topped off with a circlet or linen fillet around the head and temples. Richer women could have finer nets of metal, sometimes more like boxes, and could decorate them with jewels. Plaits could be augmented by fake hair or silk. This was frowned upon as unnatural and a sign of pride by the clergy, who as arbiters of taste and decency often found fault with women’s (and also men’s) clothing.

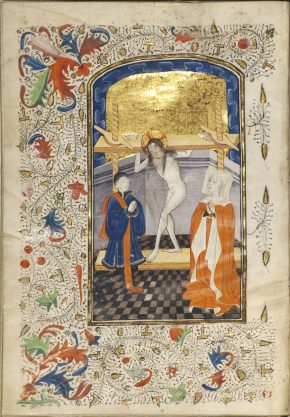

One of the more controversial fashions was for horned headdresses. The female [patron’s] horned headdress allows us to date this book to around 1440. During the 15th century women’s headwear became more extravagant, and large horns either side of the head became popular – perhaps as an exaggeration on the nets in the previous image. Horns would be padded out with wool or grass, or shaped with whalebone. Despite being worn by pious women like the lady contemplating Christ in our image, they were not popular with the church who thought them devilish.

A bourrelet (or stuffed roll) was an adaptable component of headdresses in the 15th century. Again stuffed with wool or grass they gave a larger silhouette, and could be sausage or heart shaped. This young girl simply tops her loose hair with a simple version of the bourrelet. Veils could be pinned to the bourrelet to complete the look and were sometimes starched to give more shape and volume.

Another example of the exaggerated headdress from this century, as worn by the owner of this manuscript depicted on the left hand page, is my personal favourite – the steeple. These could reach anything from 10 to 35 inches high, and would often include a veil, long enough to extend from the top of the steeple to the floor, which could be carried on the arm to prevent it dragging on the ground. Hair could be plucked along the hairline to give a higher brow. As elegant and impractical as the best fashion, it must have been difficult to move in. Even though it looked like a part of a church the clergy still thought them immodest and showy.

These fashions were mostly abandoned by the beginning of the 16th century, only to return as fancy dress in later centuries. Let’s finish with an image of an Edward Landseer portrait of Queen Victoria held in the Royal Collection. She is dressed as Queen Philippa of Hainault (Albert is King Edward III) for a costume ball held in 1842, and exhibits a bejewelled net style headdress covering her hair. If you were invited to her medieval ball, which type of medieval headdress would you wear?