The 19th century was a time of great change in European bookbinding. Social and educational reform of the previous century had led to increased levels of literacy which resulted in a greater demand for books from a wider public. The book industry responded to this demand by seeking quicker and cheaper methods of production and distribution so that books could be published in larger quantities and at a more affordable price to the buyer. Still, this need for speed did not eradicate traditional skills and it certainly didn’t dampen the desire for beautiful books.

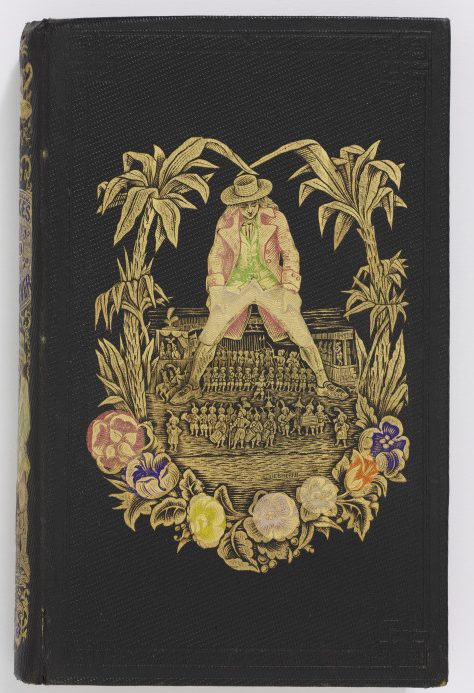

Vellum and leather had been the traditional binding materials for centuries and they continued to be used throughout the 1800s but animal skins were costly and stocks were limited. To meet commercial demand, binders needed a covering that was cheaper, more widely available and quick to produce. One solution was cloth and the cover of this French edition of Jonathan Swift’s celebrated novel Gulliver’s Travels demonstrates just how suitable it was. On the front of the book Gulliver is shown towering over the tiny inhabitants of Lilliput in a scene framed by trees and multi-coloured flowers. After stiffening the cloth with starch, gold tooling and coloured stamps similar to those used on leather covers could be applied. Cheaper binding materials therefore didn’t mean that decoration had to be compromised.

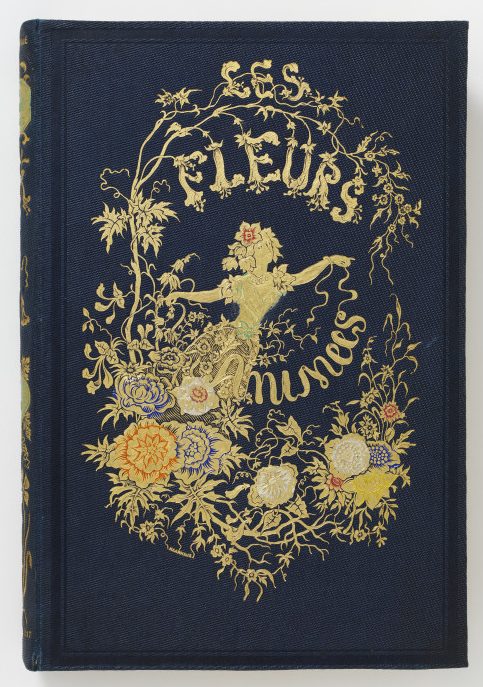

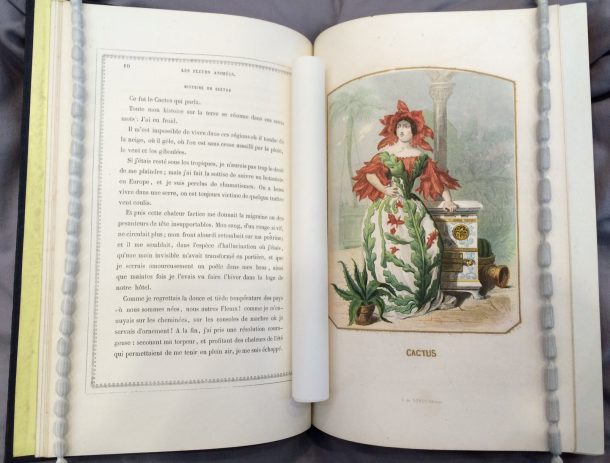

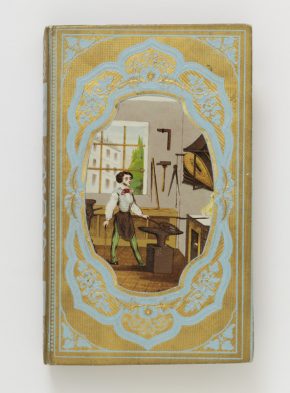

The National Art Library has many examples of these decorated cloth covers, another is on a copy of Les Fleurs Animées, a volume containing humorous, hand-coloured engravings by the eminent French caricaturist and illustrator J. J. Grandville.

The study of plants and flowers was a popular Victorian pastime spurred on by the rise of leisure reading, especially among women. The cover and the prints inside this book show flowers personified as women and dressed in elegant, often extravagant, costumes. Although the text includes detailed descriptions of the flowers in bloom, the cover and Grandville’s humorous engravings make clear that this book is designed for pleasure rather than academic study.

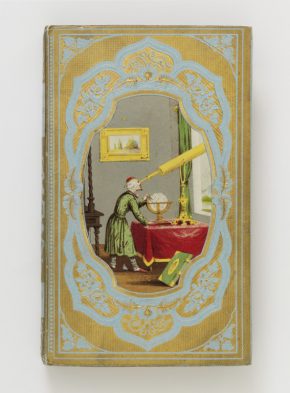

Cloth covers were one solution to reducing expenditure but publishers realised they could cut production costs further by producing their own bindings instead of paying bookbinders to make them. This pair of French history books are an example of 19th century ‘trade’ bindings: their decorated cardboard covers were designed by the publisher rather than by a bookbinder.

The industrial revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries also had an effect on book production. The pages of these history books have been prepared using machinery and are glued together instead of being sewn by hand.

In the mid-19th century there was a trend for giving books with decorative bindings as gifts and the demand for novelty in these bindings often resulted in unusual combinations of materials and techniques. The parrot on the central panel of this book’s cover has been stitched in wool onto linen and inserted into the leather binding to create a striking mix of media.

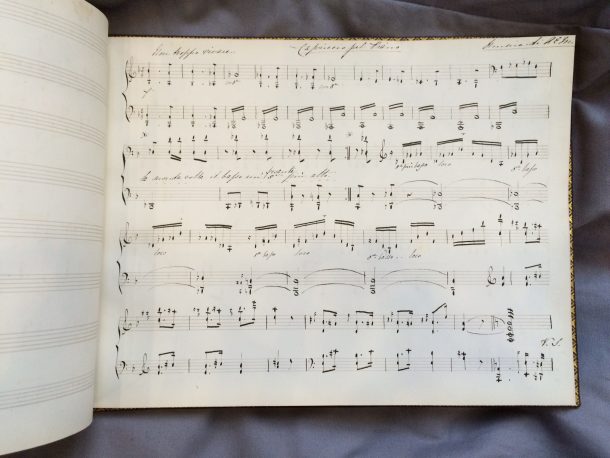

Gift books often contained poetry but this one is filled with leaves of music manuscript paper and on the first few pages the owner has transcribed songs and short pieces for piano.

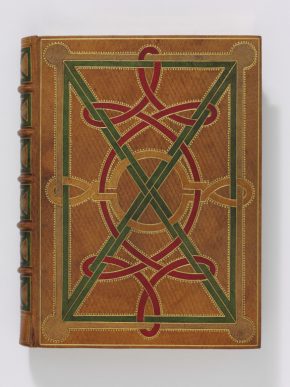

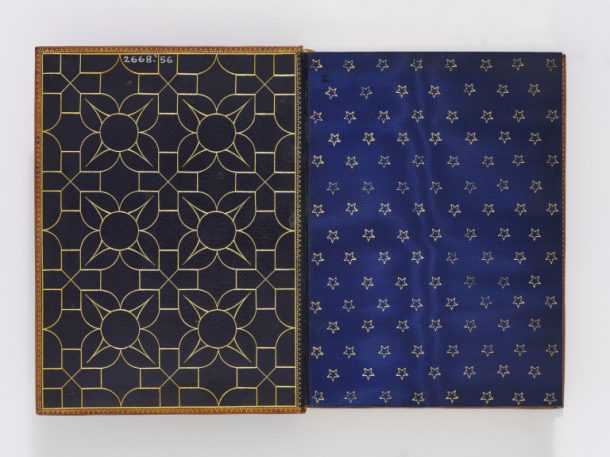

Despite new innovations, traditional bookbinding methods did not cease. In the 1840s the French bookbinding firm Gruel were commissioned by the printers Engelmann and Graf to provide a range of covers for a facsimile of illuminated manuscripts. The bindings were to be in different styles and at varying price levels so as to appeal to a wide audience with differing budgets. This example, bearing a bold strapwork design of interweaving leather inlays and beautiful dark-blue endpapers decorated with gold stars, is one of three copies in the National Art Library, each with a different binding.

A few decades after this binding was produced another member of the firm, Léon Gruel (1841-1923), wrote his Manuel Historique et Bibliographique de L’Amateur de Reliures (published 1887-1905). In it he gave examples of historic fine bindings and called on his contemporaries to demonstrate greater innovation in binding design. New materials, techniques and audiences had transformed the way books were produced, but firms such as Gruel were striving to maintain traditional skills whilst satisfing a rapidly changing market at the same time.

My 3rd great grandfather was Richard Bookbinder Perrott born 1793 in Berry Pomeroy, Devon and was a ‘Bookbinder’. I was very interested to read your article as I would really like to know what sort of books he was binding.

Yes, same here! My 3rd great grandfather, John Harper Smith, was a bookbinder in Exeter Street, Covent Garden. I loved this article, and I am always looking for information about more humble bookbinders, and what kind of work they did.

My grandfather Demal Mattson was a bookbinder at Walker Evans & Congswell Co in Charleston, SC in the late 1800s-early 1900s. Were there dangerous materials in the process that affected health?