This spattered jama (skirted robe), belonging to a man’s court ensemble, has one of the most voluminous skirts in the V&A’s dress collection. It certainly has the longest hem; constructed from 352 triangular panels sewn together and gathered at the waist, the skirt’s hem measures a stunning 92.2 metres (there is more about the jama’s design and significance here). The vast amounts of fine quality muslin used to make this stylish garment and its corresponding paijama (drawstring trousers), kurta (tunic), and accessories, suggest its original owner was a person of high status. I looked to the museum’s acquisition records and registered papers, hoping to find out more.

A mystifying letter

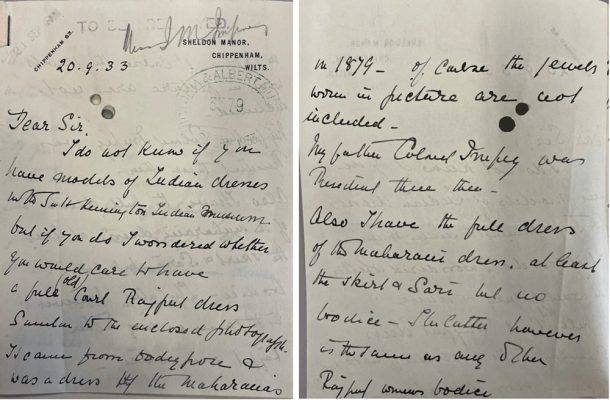

In September 1933, A.D. Campbell, the Keeper of the Indian collections at the V&A, received a letter from Miss Isabella M. Impey offering a Rajput court ensemble to the museum. She wrote that the ensemble ‘came from Oodeypore (Udaipur) and was a dress [illegible] the Maharana’s in 1879 – of course the jewels worn in picture are not included. My father Colonel Impey was resident there then.’

Miss Impey’s incomplete account raises several questions; was 1879 the date the ensemble was made, or worn, or both? Did the ensemble belong to Maharana Sajjan Singh (1859 – 1884), ruler of Udaipur from 1874 to 1884, and did he actually wear it? And how did it come to be in Colonel Impey’s possession?

The Keeper suspected that Miss Impey was in error about the provenance, as the style of the ensemble’s turban was ‘undoubtedly that of the court of Jodhpur which was further North in the Rajputana (Rajasthan) than Udaipur’. In his letter to the Director seeking approval for the acquisition, the Keeper wrote ‘And the Portrait of the Jodhpur Maharaja reigning in 1879, Jaswant Singh II, G.C.S.I., agrees closely with the photographs sent by Miss Impey (see large envelope in these R.Ps). (See Hendley, Rulers of India and chiefs of Rajputana, pl.17, no.30)’.

Unfortunately, the Registered Papers did not contain the photographs sent by Miss Impey with her note. In his description of the robe, the Keeper wrote ‘Worn probably by Maharaja Jaswant Singh II, G.C.S.I. (1838–1895)’, ruler of Jodhpur from 1873 to 1895.

On further investigation, I learned that Miss Isabella M. Impey was the daughter of Eugene Clutterbuck Impey (1830–1904) and Isabella Catherine Lawrence (1836–1902). Her father was an important figure in early photography in India. Eugene Impey belonged to a well-known colonial family and started his military career in India in April 1851 in the 5th Regiment of Bengal Native Infantry. In 1858, he became a Political Agent at Alwar in North-Eastern Rajasthan. Later, he served as British Political Agent to Marwar (Jodhpur) for two terms between 1865 and 1873.

During Impey’s career as a political administrator in the Princely States of the Rajputana (Rajasthan) he had the opportunity to study and photograph Indian architecture and the courtly splendour of the region. From the album ‘Delhi, Agra and Rajpootana, illustrated by eighty photographs, taken by Captain E. C. Impey’, published in 1865, we know he travelled to Amber, Jaipur, Alwar and Bundi in Rajasthan. Impey retired from service on 31 December in 1878 during the reign of Maharaja Jaswant Singh II. He spent his retirement years in Oxford, where he died on 11 November 1904, which suggests this spattered jama may have come into his possession before 1879.

There is no evidence that Impey visited or served in Udaipur. So, did the ensemble actually belong to Maharaja Jaswant Singh II of Jodhpur? With a little luck, I found a photograph that fits the Keeper’s description of the images sent by Isabella in the collection of Lawrence Impey, the great-grandson of Eugene Clutterbuck Impey. The image titled ‘Maharajah Tukht Singh [of Jodhpur] in full Durbar (court) costume’ is part of a small album of platinum prints taken by Eugene in around 1870. The uneven colouring on the jama and the dye splodges in the black and white photograph resemble the spatter pattern on the jama in the V&A’s collection. Could this be the photograph referenced in the acquisition file? If it was, did the V&A’s jama actually belong to Maharaja Takht Singh (1819 – 1873)? As the ruler of Jodhpur from 1843 to 1873, and the father of Maharaja Jaswant Singh II, if it belonged to Maharaja Takht Singh then the ensemble is older than was thought when it was acquired.

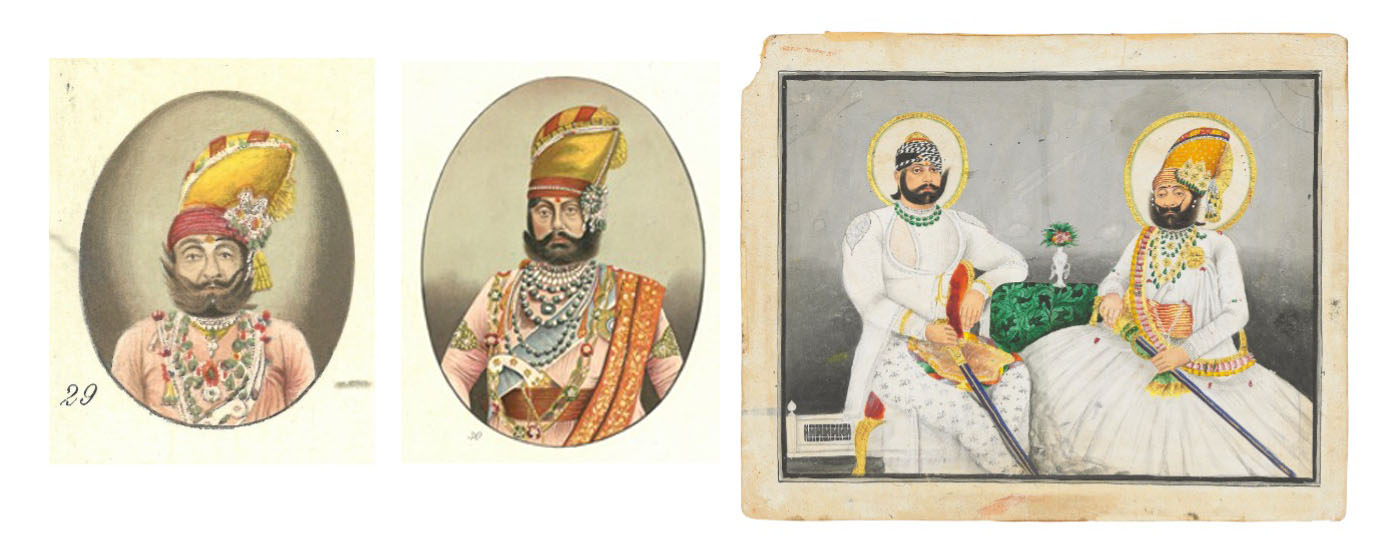

The uncertainty in the acquisition records and Eugene Impey’s presence in the Jodhpur court during the reign of both rulers gave the impression that the jama could belong to either of them. I turned to study several other paintings and photographs for an answer. In the portraits (above) of Jaswant Singh II with his father, Maharaja Takht Singh, from Thomas Holbein Hendley’s 1897 publication Rulers of India and the chiefs of Rajputana (1550–1897), we see them dressed in a similar style of jama. Hendley was the Administrative Medical Officer in Rajputana from 1895 to 1897 and visited most of its capitals at the time. He had personal acquaintance with the living chiefs and some of their predecessors. He was particularly interested pictures and portraits of the native princes which he published in his album.

I now found another portrait to compare the ones seen in Hendley’s album. In this double-portrait (above) showing the two rulers side-by-side, we can see that not only is Jaswant Singh II in a different style of dress, he also had a larger form than his father, particularly in the breadth of the shoulders and chest. The portraits compared above, the photograph taken by Eugene Impey during his tenure in Jodhpur, and the smaller size of the jama itself, suggest that the ensemble could have belonged to Maharaja Takht Singh.

A modified garment

Convinced I had found the wearer, I popped over to the Conservation Studio to have a closer look at the ensemble again. I noticed several differences between the jama and the one in the photograph. The fastenings, used on the shoulder and under the arm to secure the double-breasted bodice, and the insufficient gathering on the cuff, suggest that both lengths are shorter than in the photograph. Also, the sleeves and voluminous skirt of the jama are trimmed with gota (tinsel ribbons) and gota moti borders of varying widths – unlike the one in the photograph. I wondered if the original garment was altered. Is the gota contemporary to the garment? Were these modifications made before it came into the possession of the Impey family, or later in England?

Further examination of the jama led to two other curious discoveries. Firstly, the presence of make-up stains in the collar of jama and kurta suggest that the ensemble may have been worn before it came to the museum. What kind of life did the ensemble have before it came into the South Asian Collection? Was it worn by a member of the Impey family in its later years when back in England? And secondly, I found an intriguing inscription ‘191’ stylistically rendered in a deep blue colour along with two flower motifs hand embroidered in metal thread inside the bottom of the skirt. The purpose of this stitching is unclear.

While I dwell on these tantalising questions and continue my research into this fascinating garment, you can read more about the conservation of the jama carried out by Annabelle Camp as part of her work placement at the V&A for the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation here.