Fans of Games of Thrones know how impressive an important seat of power can be. This is also true in medieval manuscripts where images of thrones feature often when depicting earthly and heavenly rulers. You don’t, however, always need a fancy throne like the Iron Throne of Westeros to show your importance; any chair with arms and a back was quite unusual in medieval times and a sign of status. Keep reading to see some medieval images of impressive thrones and other seats of power, and see what they tell us about the importance of those who sit on them.

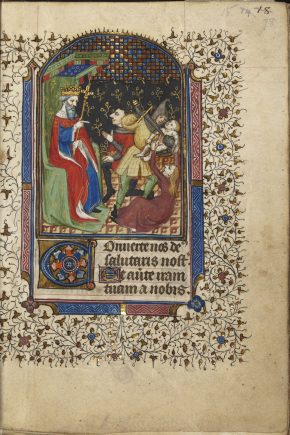

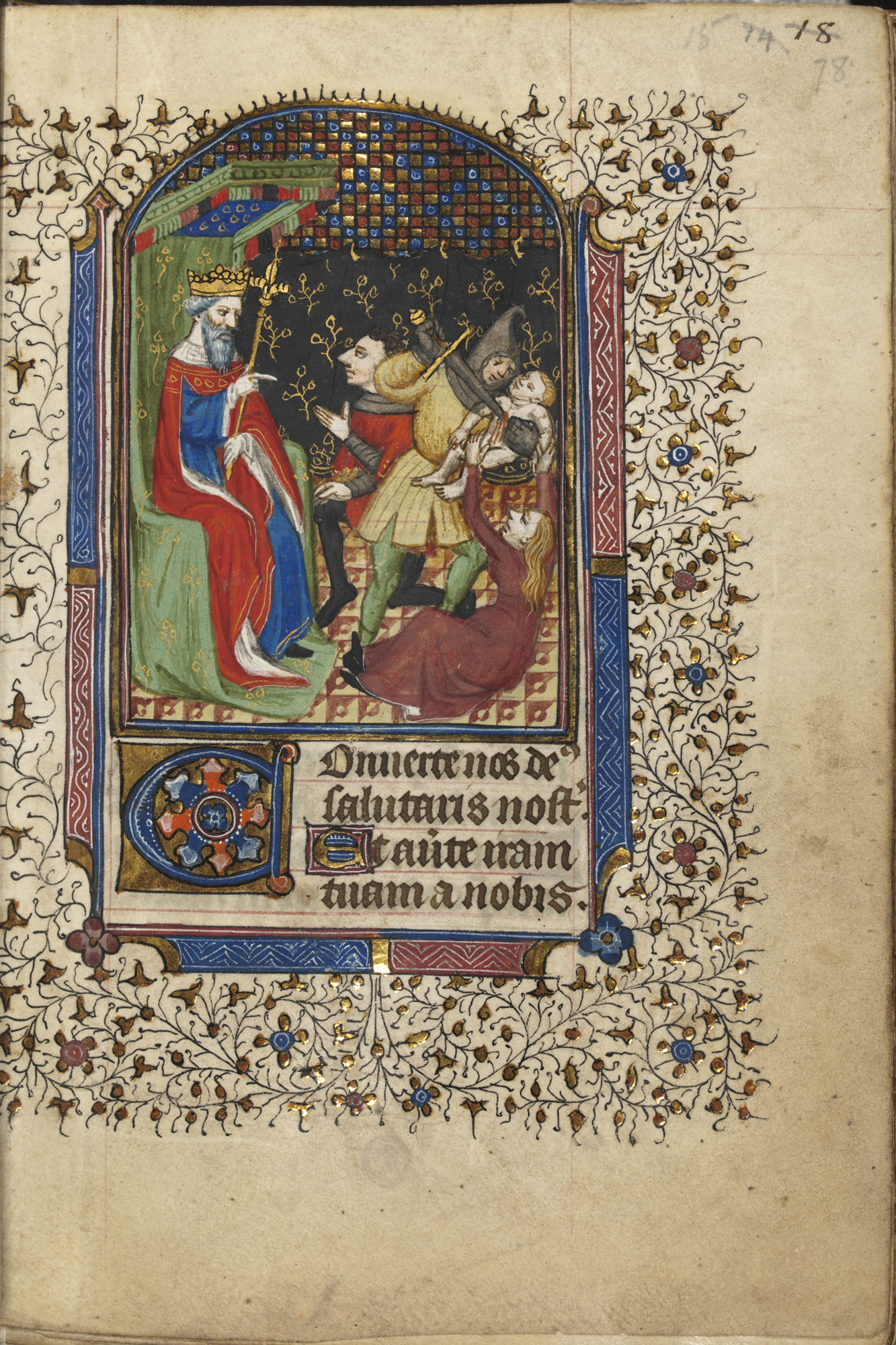

This image shows King Herod sitting on a canopied throne, ordering the killing of infants as described in Matthew’s Gospel.

Real royal thrones seem to have conventionally have been made of stone. The famous 8th century throne of Emperor Charlemagne in Aachen was made of marble. This Italian late medieval ceremonial chair was made of wood.

Like Herod’s, thrones could be dressed with luxury textiles to express opulence. They would not have been particularly comfortable even with a few sumptuous pillows – thrones (and chairs) were for looking important, not lounging.

In the manuscript image a man kneels in front of Herod, either taking orders or perhaps pleading for clemency. A ruler’s prerogative was to be seated while all others around them stood or kneeled. This was still the case in 17th century France, where sitting in the presence of Louis XIV was a special privilege given only to high-ranking court figures such as duchesses who would have a special stool (but not a chair!) called a taboret to sit upon.

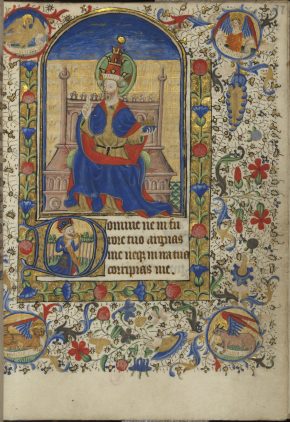

In manuscripts, God is often pictured enthroned as a heavenly ruler with authority over earthly kings. This image shows God on an elaborate, pinnacled throne while the biblical King David (with his harp) kneels in the letter D below.

This throne image is typical of those influenced by the late Medieval Gothic style – it has features like spires and arches that make it look very architectural – more like a church building than a place to sit. The link between throne and church is also a linguistic one, going back to ‘cathedra’, the Greek word for seat, which gives us our word ‘cathedral’. Someone speaking ‘ex cathedra’ – from the chair – was speaking with power and authority.

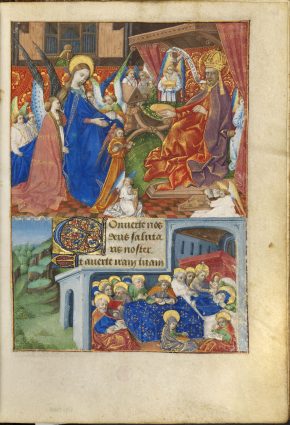

An important festival in the church calendar is the assumption of the Virgin Mary, when she ascends to heaven after her death. It is celebrated on 15th August. In manuscripts this is often illustrated by God placing Mary on a heavenly throne. From the 12th century, belief in the power of the Virgin Mary to intercede in prayers increased; images such as this demonstrate her powerful position in heaven and close relationship with God.

The chair that God is gesturing towards, for Mary to take, is a Roman-style x-frame chair. In Roman times, metal chairs of this type were used during campaigns by generals – an important role in such a martial culture. In Medieval times, bishops would often use them as a seat of authority. As they could be folded, they could be taken to wherever the bishop needed to speak ‘ex-cathedra’. They could be upholstered with rich textiles and trimmings like the 17th century Juxon chair.

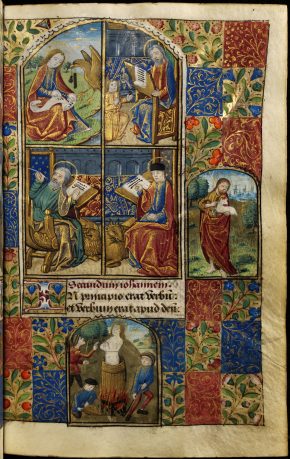

Gospel writers are often depicted in chairs, such as in the image below where Matthew and Mark and Luke are seated on a range of different chairs. (In this image John is not seated on a chair, but is shown sitting outside to reflect the tradition that he had his visions on the island of Patmos.)

The Gospel writers are not rulers, and the chairs they sit on are not thrones, but their depiction on a chair shows they have importance and authority as the men who wrote down the life and teachings of Christ. These chairs are similar to those found in larger households in northern Europe, where there might only be one armchair which was solely for use of the most important person, usually the master of the house or a VIP guest. The armchair pictured below, which includes a storage box within the seat, is an example of such a chair.

The rest of the household would have sat on simpler lower stools, benches or cushions. If you would like to find out what you could sit on if you were not a King, a deity or a Gospel writer, read my accompanying blog about where to put your more lowly medieval bottom.

These images, and more, are available to view in the National Art Library and in the Prints and Drawings Study Room, so come along and pull up a chair.

Thanks this is a very famous game.

Thank you for sharing this stuff

Very nice stuff there