During a recent visit back home to Bangalore, I had the pleasure of exploring Kaash Space, a new centre connecting India’s craft traditions with cutting-edge contemporary design. Here I met resident artist Dr Vijay Siddramappa Hagargundgi, a revivalist of the Surapura school, a style of painting characterised by fluid lines, vibrant colours, delicate gesso, and gold leaf. I was unfamiliar with the Surapura (or Shorapur) style, and his work captivated me.

Born in Gulbarga, Karnataka, in 1956, Dr Hagargundgi trained at the art school in Shantiniketan, West Bengal, and later studied under the renowned artist Dwarka Prasad Sharma in Jaipur. However, his passion led him back home, where he creates remarkable works inspired by Hindu mythology and literature, exploring themes from the Shiva Purana, Dashavatara, Navagraha, and Kama Sutra.

Initially, Dr Hagargundgi approached me with much quietness. But, over time, he answered my myriad questions about his practice with keen insight and passion. I was struck by his extensive knowledge of Hindu mythology and iconography, which inspired me to examine the South Indian gold-leaf paintings at the V&A.

Surapura school of art

The history of the Surapura school traces back to the Battle of Talikota in 1565. After the Vijayanagar Empire was defeated by the Deccan Sultanates, many artists from the region migrated in search of new opportunities, adapting their styles to suit the tastes of new patrons, which led to the emergence of new regional styles.

Surapura (now in present-day Karnataka) and Rajahmundry (Rajamahendravaranam, in present-day Andhra Pradesh) became significant centers of artistic activity, alongside major hubs of Deccani painting such as Ahmednagar, Bijapur, Golconda, and Hyderabad. In Surapura, artists produced a large volume of devotional and secular paintings, including portraits, under the patronage of Raja Venkatappa Naik IV (from 1773 to 1858). After the death of the Raja, Surapura was annexed by the British and transferred to the dominions of the Nizam of Hyderabad, which led to a slow decline in artistic production. Today, only a few examples of this style survive in museums and private collections, both in India and abroad.

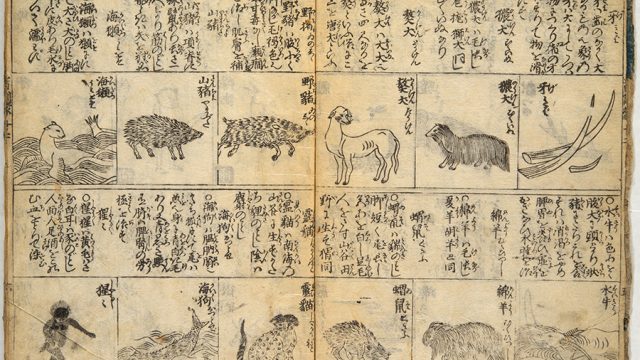

The Surapura style shares strong similarities with the Mysore and Tanjore traditions, especially in its use of gesso, vibrant colours, and decorative elements such as gold leaf and semi-precious stones. Surapura paintings can be distinguished from other South Indian gold leaf artworks, however, by their unique scale variations in characters and objects within the same composition, elegantly drawn fine lines, and rich detailing, particularly in the gold work.

There is limited writing on Surapura paintings compared to other South Indian painting schools. An unverified source suggests that the earliest examples of Surapura-style murals were discovered on the walls of temples and homes in Surapura and near Gulbarga, Karnataka. Over time, artists adapted their works to various mediums, including wood and paper. By the early 20th century, mass-produced lithographic popular prints of Hindu deities, also known as Calendar Art, began to replace the regional painting styles, accelerating the decline of the Surapura school.

Revival of the Surapura style

Dr. Vijay Hagargundugi has been a driving force in reviving the Surapura style, forming an extensive collection of local artworks – the foundation of his early practice. Recently returning from retirement, at Kaash Space he experimented with merging traditional and contemporary techniques, in line drawings and works with colour. During our discussions, he showed me four vivid colour-blocked sheets with faint pencil illustrations of Hanuman with a Shivalinga from the Ramayana, Markandeya and Urdwareteshwara from the Shiva Purana and Raktabija Samhara from the Devi Purana.

One of the most captivating features of Dr Hagargundgi’s work is the use of composite figures that emerge out of the main composition into the borders. He applies four layers of natural pigments, occasionally incorporating a fifth layer with a drybrush to ensure longevity. He still uses oyster shells and coconuts as a palette to prevent colour change, a dated but reliable practice. Each artwork is prepared with gesso, which forms a subtle relief that forms the base layer for the application of gold leaf.

It was fascinating to watch the application of the layers of gesso applied meticulously and the laborious process of gold leaf application. Before starting, Dr Hagargundgi showed me various gold foils used in contemporary Thanjavur, Mysuru, and Rajasthani paintings, as well as Hilkari, a powdered gold from Udaipur. He then carefully retrieved a small piece of the Udaipur foil, stored between two sheets of paper from a Mirza Galib book he was reading. He cut a tiny piece and applied it to the painting using gum Arabic. Despite his trembling hands, the precision of the application of the glimmering gold was remarkable! I found myself in awe, watching him enter a meditative state as he worked, each piece of gold applied with patience and reverence.

South Indian gold-leaf paintings at the V&A

Back in London, I visited the V&A paintings store to examine the gilded works from South India in our collections. The V&A houses approximately 650 artworks from South India, on paper, wood, mica, ivory, and glass. Many of these paintings prominently feature gold leaf and its variants. Among these, a few are embedded with glass beads, semi-precious stones, fragmented mirrors, or gesso, to produce a highly textured surface, similar to the bas relief divine sculptures in Hindu temples. These include the Thanjavur and Mysuru-style paintings, which usually illustrate religious subjects and may be divided into three genres – mythological scenes, icons, and imperial portraits.

One of our finest Thanjavur works on glass is the portrait of Raja Sarabhoji (1777 – 1832) of Tanjore, made in about 1860. Sarabhaji was the last ruler of the Bhonsle dynasty of the Maratha principality of Thanjavur. The Raja holds a flower in his hand, a common feature of portraits at the time. Gold-leaf is used to decorate his turban and jewellery. This painting is accompanied by a portrait of a South Indian dancing girl, holding a similar flower. She is adorned with gilded jewels.

Our collection also includes a set of four 19th-century religious paintings that possibly belong to the Thanjavur or Mysuru School of Art, embellished with guiding and mirror fragments. The classification of ‘Thanjavur painting’ can be perplexing, as it shares significant similarities with sister styles that developed concurrently in Mysore (Karnataka) and Andhra Pradesh. Important pilgrimage sites, such as Tiruchirappalli and Madurai in Tamil Nadu and Tirupati in Andhra Pradesh, also served as thriving production centers for these artworks. The first painting depicts Brahma within an arched temple structure, crowned with a Chattri (parasol) above his head. He is attended by Vishnu and Shiva on the right and Garuda on the left. The second painting shows Shiva and Parvati mounted on Nandi while several Brahmins attend to them.

In the Tirupati style, we hold four early 19th-century religious paintings. One of the most notable is a painting of Vishnu with, possibly, Lakshmi on the left and Varaha on the right. Gold-leaf or powder is applied to their adornments. The deities are seated within gilded arches decorated with Yalis on the top, while the drapery within is embellished with lotus garlands.

While these religious works share common themes and techniques, their distinctiveness can be subtle. The paintings typically feature a symmetrical layout, with divine figures prominently positioned at the center, enclosed by architectural elements like rounded arches and pillared halls. Vibrant colours, gesso and gold work create a unifying effect, yet each piece reflects a unique style. Only through further research and exploration of additional examples can we effectively differentiate and celebrate the various South Indian painting schools.

If you’d like to make an appointment to view these works at the V&A, South Kensington, please email: asia.enquiries@vam.ac.uk

I know Dr. v. Vijay hagargundagi sir personally and i have seen some rarest paintings and antique collection in their museum you we always appreciate you sir for dedication and your hardwork

Thank you sir