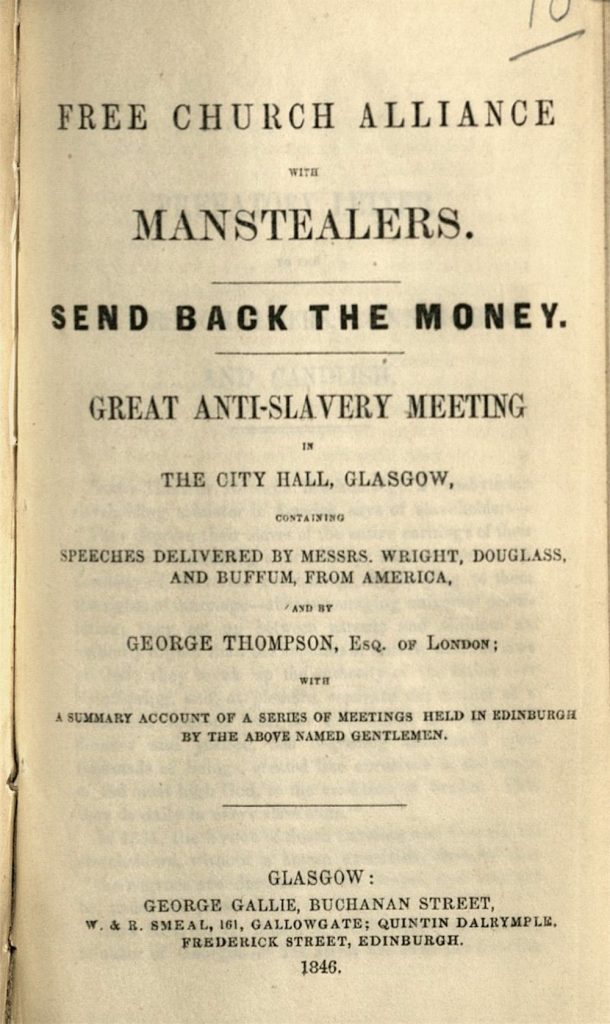

When early photographic pioneers Robert Adamson (1821 – 1848) and David Octavius Hill (1802 – 1870) were busy producing their pathbreaking calotypes in 1840s Edinburgh, a rallying call was heard on the streets of the Scottish capital: ‘Send back the money!’ Leading the call was American abolitionist Frederick Douglass who, in 1846, had embarked on a tour of Britain and Ireland. He directed his aim at the Free Church of Scotland, which had accepted funds from the profits of enslavement in the American South. Douglass demanded the ministers send it back:

Send back the Money! send it back!

’Tis dark polluted gold;

’Twas wrung from human flesh and bones,

By agonies untold:

There’s not a mite in all the sum

But what is stained with blood;

There’s not a mite in all the sum

But what is cursed of God.

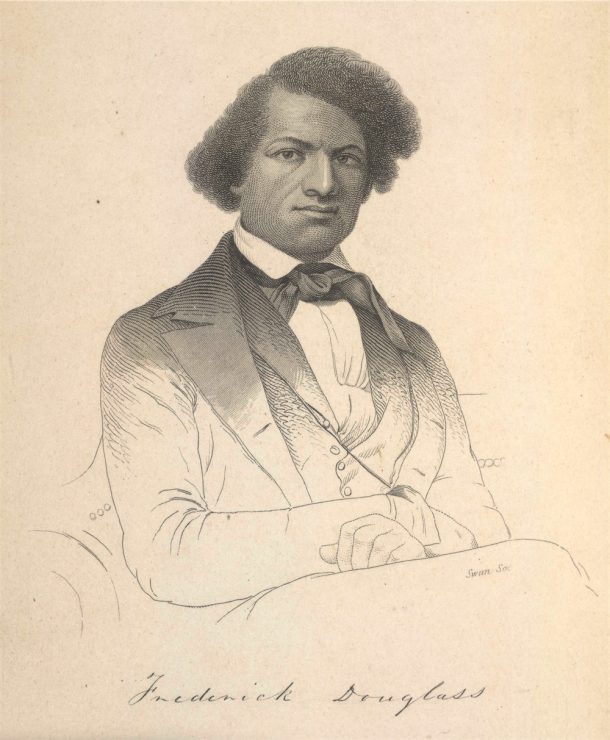

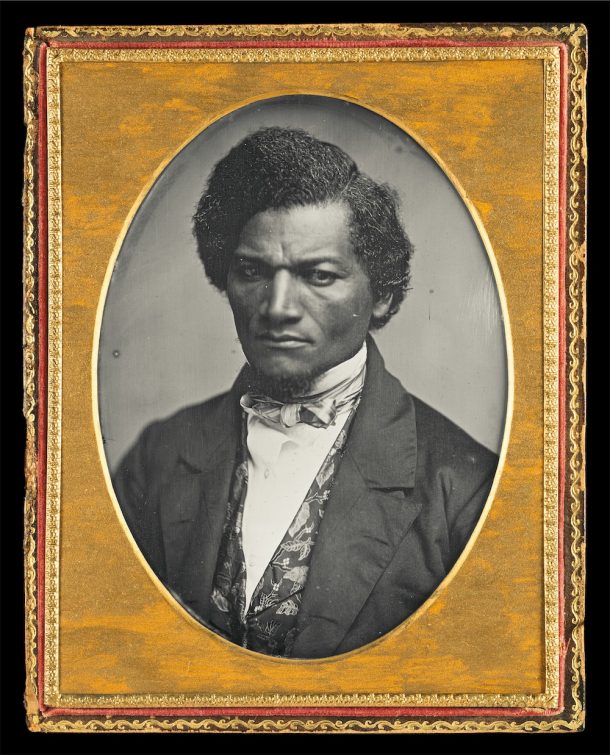

Frederick Douglass and David Octavius Hill don’t often appear in the same sentence. But there are good reasons to bring these mid-19th century figures together. As Scotland begins the process of confronting its deep ties with enslavement and empire, it is time we located early Scottish photography in its colonial context. By bringing the American abolitionist and Scottish artist into dialogue, we can ask new questions of some of the most foundational works of photography.

Douglass and Hill almost certainly never met, but they moved in similar circles and held interests in common. Douglass held Scotland, particularly its landscape and literature, in high regard – he famously named himself after a character in Sir Walter Scott’s Lady of the Lake. But it was the national bard, Robert Burns, to whom he returned time and again throughout his life. Hill was similarly taken by the poet and illustrated the 1840 book The Land of Burns. Both men sought out Burns’ younger sister, Isabella, and their encounters survive today: Hill’s calotype photograph of her is held at the National Galleries of Scotland, while Douglass’ recollections of meeting the poet’s sister are captured in the Frederick Douglass Papers.

They also shared an interest in photography. Douglass, famed for his emancipatory politics and extraordinary oratory skills, was an early theorist of photography. As early as 1861 he addressed questions of vision and justice in his Lecture on Pictures: ‘what was once the exclusive luxury of the rich and great is now within reach of all’, Douglass wrote:

The humbled servant girl whose income is but a few shillings per week may now possess a more perfect likeness of herself than noble ladies and court royalty, with all its precious treasures could purchase fifty years ago.

Douglass understood the power and potential of photography and placed himself in the frame. In fact, he became the most photographed American of the 19th century and purposefully used photography to advance his emancipatory projects.

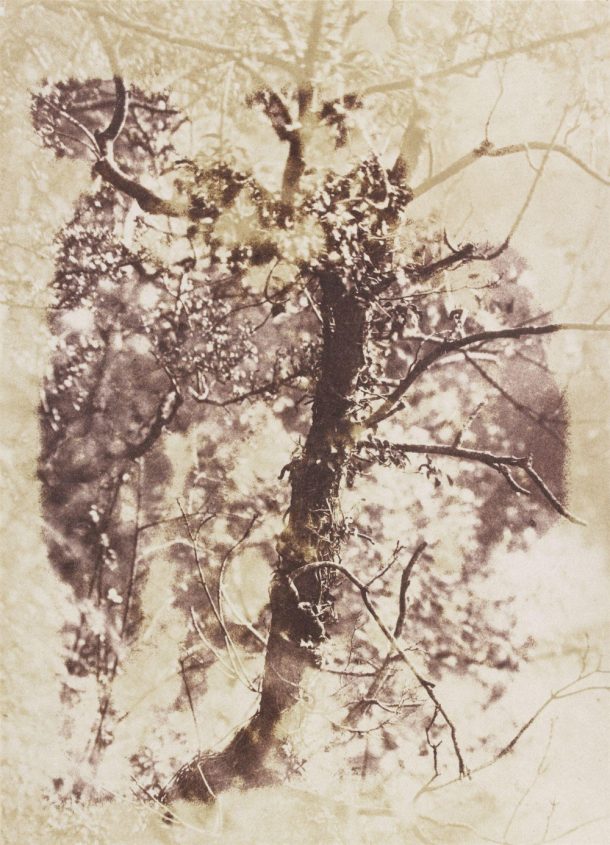

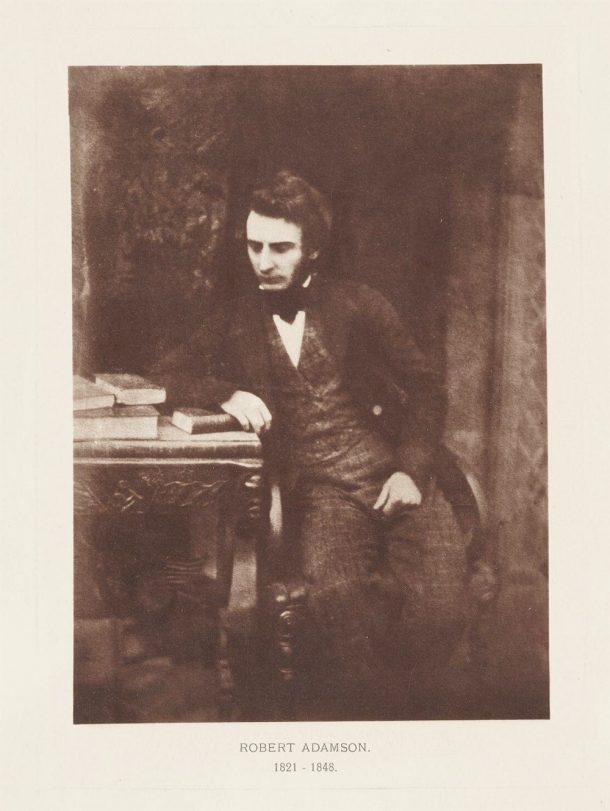

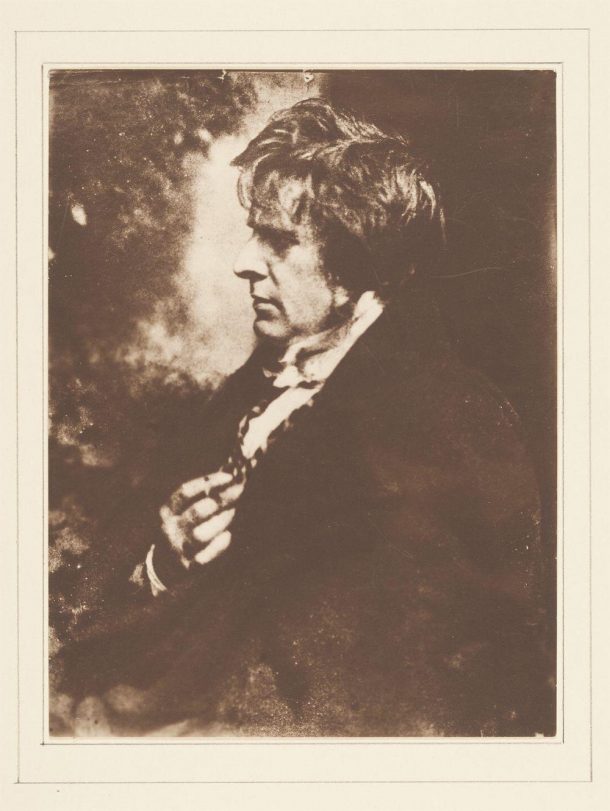

Hill, meanwhile, was a champion of the calotype, a revolutionary invention declared by William Henry Fox Talbot in 1839. The calotype is a paper process in which silver iodide is used to create a negative ‘photogenic drawing’ which is then reproduced as a ‘salted silver’ positive paper print. Together with his collaborator, Robert Adamson, and assistant Jessie Mann, they pioneered this method in Edinburgh from 1843 to 1848.

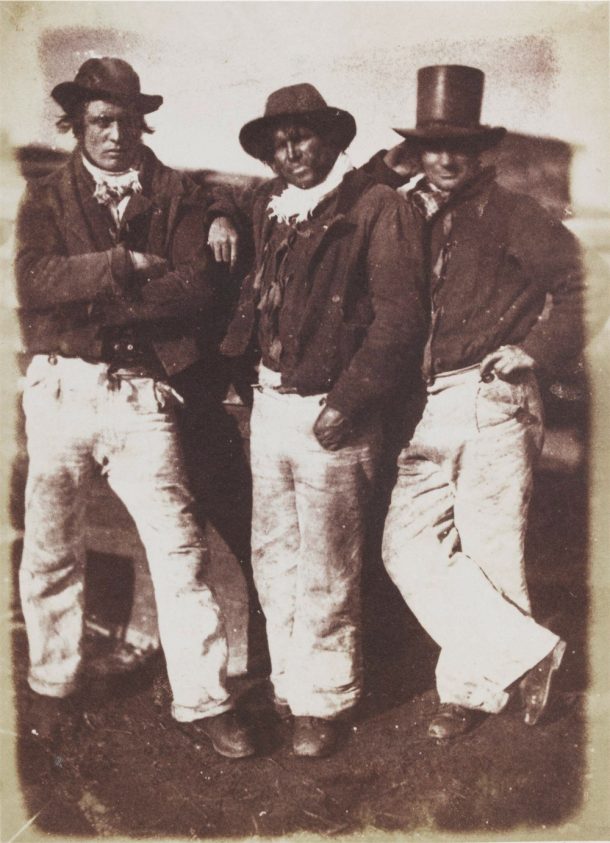

Between them they produced a collection of prints that today are known not only as one of the foundational works of nineteenth-century photography, but as one of the first series of photographs to be self-consciously presented as art. Their subjects ranged from Scottish landscapes, artists, Free Church ministers, Edinburgh high society and military, to perhaps most famously, the working fishing community of Newhaven. At times, Hill borrowed from Walter Scott when titling these works, but in the main, he chose the more radical act of naming his subjects, irrespective of class.

Both Douglass and Hill appreciated the importance of representation. Though there is no known record of the two men meeting, they likely stood just metres apart on 1 May 1846. Douglass was in Edinburgh delivering a rousing speech to a packed meeting of the ‘Edinburgh Ladies Emancipation Society’ in the Waterloo Rooms. Meanwhile, making the most of the spring sun, Hill was engaged in outdoor calotype activity at Rock House, situated directly above the hall where Douglass was speaking. From his vantage point in their garden studio, he must have been able to see the crowds assembling to hear the ‘electrifying’ orator.

What brought Douglass to Scotland, and to a venue so close to Hill’s studio, was the cause of abolition. Douglass spent 19 months in total in the UK and, while he wasn’t the first Black abolitionist to visit, he was certainly the most renowned. While in Scotland he became immersed in the campaign against the Free Church of Scotland for receiving funds from enslaved labour in the United States. Douglass denounced the Church for accepting the ‘price of blood into its treasury’ and led the campaign to ‘send back the money’ with the Edinburgh Ladies Emancipation Society and other abolitionists in Glasgow, Dundee, Aberdeen and beyond. A meeting was arranged between Douglass and the leading ministers of the Free Church, but it never occurred. The ‘blood stained money’ was never returned. In his autobiography, Douglass lamented that the Church:

Through its leading divines, instead of repenting and seeking to amend the mistake into which it had fallen, caused that mistake to become a flagrant sin by undertaking to defend, in the name of God and the Bible, the principle not only of taking the money of slave-dealers to build churches and thus extend the gospel, but of holding fellowship with the traffickers in human flesh.

Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, Frederick Douglass, 1881, p.695

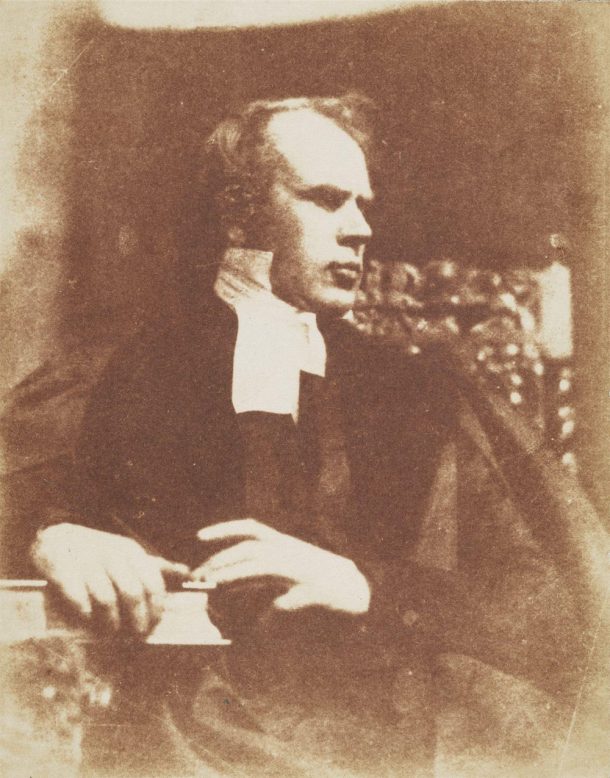

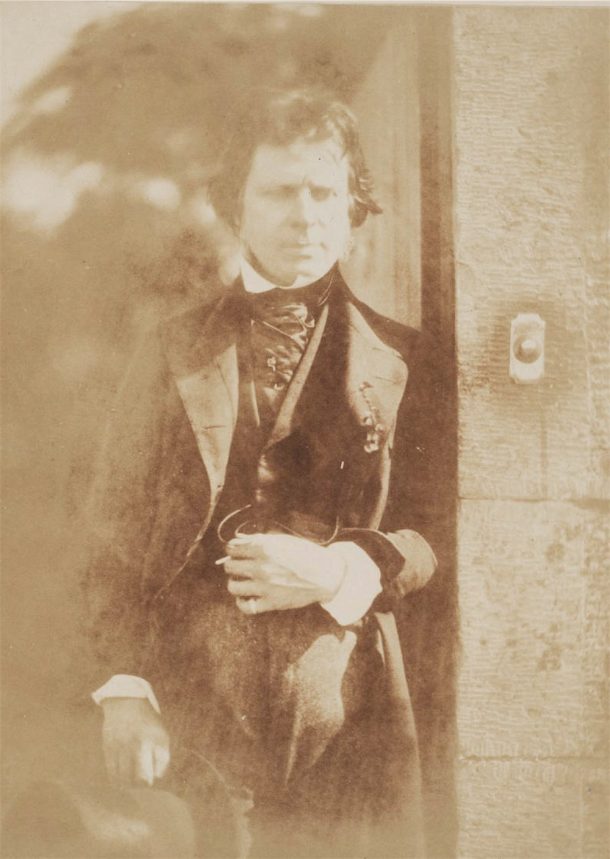

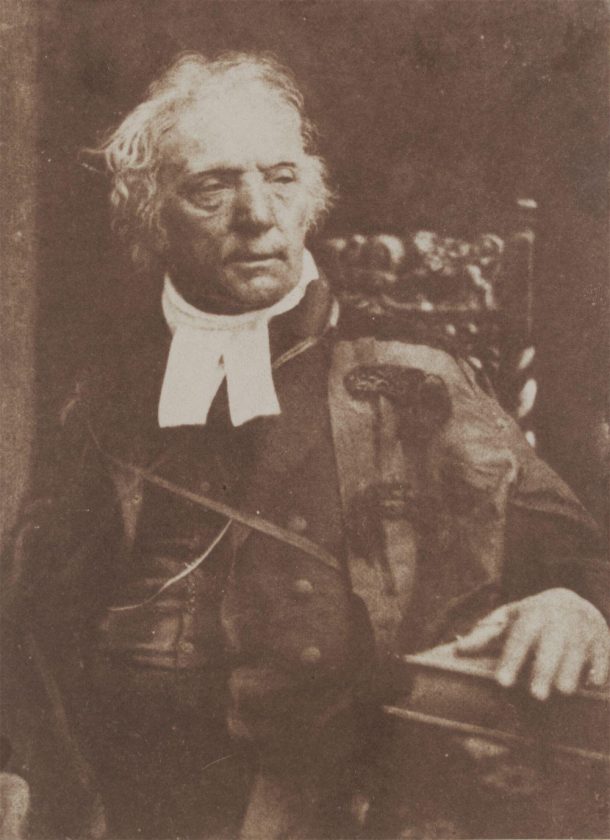

Hill was also connected to the Free Church, though in different ways and for different reasons. Its formation brought about an unprecedented split within the Church of Scotland, which saw hundreds of ministers break away and establish their own institution. This seismic event, known as ‘The Disruption’, was famously memorialised in paint by Hill. In what was his most ambitious work to date, Hill established a large-scale canvas to depict the scene of dissenting ministers signing their new deeds to form the breakaway church. Yet this was no ordinary painting. Hill’s portraits were based on calotype photographs; portraits he had taken with Adamson. What was originally conceived as a tool to assist a painting, became one of the most significant bodies of photographic work to have ever been made in Scotland. Together with assistant Jessie Mann, they produced hundreds photographic portraits and thousands of prints, the majority taken and made in their Edinburgh studio.

It is quite conceivable then, that as Douglass was addressing his packed audience at the Waterloo Rooms, just metres away, Hill was at Rock House calotyping one of the Free Church ministers – the very object of Douglass’ searing critique.

Photographed in the year of The Disruption, Welsh was a key figure in the formation of the Free Church, and invited ministers to ‘separate from the Establishment’.

With the transfer of the Royal Photographic Society collection, over 300 hundred works belonging to Hill & Adamson can now be found among the V&A Collections, including portraits of the aforementioned ministers. Without doubt, Hill & Adamson turned their camera to their subjects with care and vision. Not only are their calotypes firmly established within the canon of early photography, they are widely celebrated as works of photographic art. But just as the life of Robert Burns has been critically reappraised, so too must these works of early photography. By bringing Hill and Douglass into dialogue, we can locate photography in its ongoing histories of empire. As Douglass said of photography in 1861, ‘men of all conditions may [now] see themselves as others see them’. Today, we ought to make sure these photographic portraits are seen in their full light.

Further reading

Frederick Douglass and Scotland, 1846: Living an Antislavery Life, Alasdair Pettinger, 2020

A Perfect Chemistry: Photographs by Hill and Adamson, Anne M. Lyden, 2017

Vision and Justice, Aperture, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., 2016

Send Back the Money! The Free Church of Scotland and American Slavery, Iain Whyte, 2012

The Personal Art of David Octavius Hill, Sara Stevenson, 2002

Great read, it brings the context, life and world to life of the work. Also correctly draws attention to Douglas and the work he did in the UK.

Really interesting post, thank you. I had no idea of Frederick Douglass’s interest in photography, fascinating!

I find your work on calotype and photographic history absolutely fascinating. Looking forward to reading more works on your research into this area.