Research undertaken in partnership with the Business of Fashion Textile and Technology at London College of Fashion

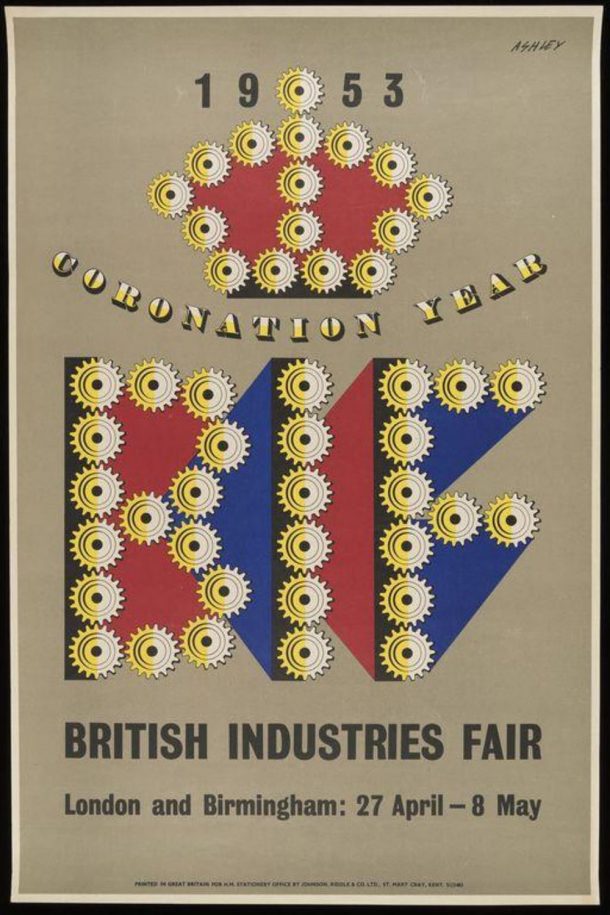

For 40 years (1920 – 60) the British Industries Fair (BIF) was the leading trade show in Britain . Manufacturers would often use the BIF as an opportunity to set their latest development or scientific innovations before a discerning public. In 1953, Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) took a large dual aspect stand at Earls Court branch of the BIF to showcase their two newest trademarked textile products. ICI was a British chemical conglomerate, at one time the largest manufacturer of commercial products in Britain. On the stand was a type of polyester, diethyl terephthalate, which they marketed as – the much easier to pronounce – Terylene. The second product Ardil was slightly more unusual; it was a soft wool-like yarn made from waste peanuts.

So what lead ICI to produce a textile made from peanut waste? In the early 20th century manufacturers were constantly seeking new ways to mass-produce fibres for textiles to clothe a rapidly growing population. Scientists began to explore ways of synthesising natural protein fibres such as wool by chemically treating proteins to make them more amenable to being spun into yarns. Fibres made in this way became known as regenerated protein fibres (RPFs). Scientists had been experimenting with RPFs as far back as the late 1800s when Adam Millar patented a filament made from gelatine. A variety of different protein sources were experimented with – including eggs and blood albumen, but few made it into commercial production. In 1936, ICI purchased the patent that would later become Ardil, spending the next 20 years developing it for commercial production. Though early RPF experiments showed promise, as they closely mimicked the behaviour of natural fibres like wool, they had low tensile strength. As a result, RPFs were often seen as inferior substitutes for natural fibres. Despite these early issues, ICI were keen to press on investing £2.1 million into a new factory to produce Ardil in 1949. By 1951, Ardil was commercially available at scale and, in 1953, ICI considered the BIF to be the perfect launchpad to introduce their new product.

ICI regularly commissioned leading textile designers to work with their new products. To adorn their stand and demonstrate the properties of Ardil they approached Tibor Reich, a pioneering mid-century textile designer known for his love of colour and playful use of texture. Born in Budapest, Hungary, in 1916, to a family of traditional Hungarian folk textile manufacturers, Reich initially studied architecture before studying textile technology at the University of Leeds. After graduating he worked on several important commissions, including ‘Princess’ – a fabric designed for Elizabeth II to celebrate her marriage to Prince Phillip. In 1945 he set up his own mill in Stratford Upon Avon in order to have complete freedom to produce his unconventional designs. He developed a specific technique, ‘Fotexur,’ for producing print designs, generating repeating patterns from high contrast photographs. Perhaps due to his background in textile technology, he worked with new materials wherever possible, including Lurex, a yarn made from thin aluminium foil. By 1953 Tibor’s profile as a provocative and highly contemporary designer was well established.

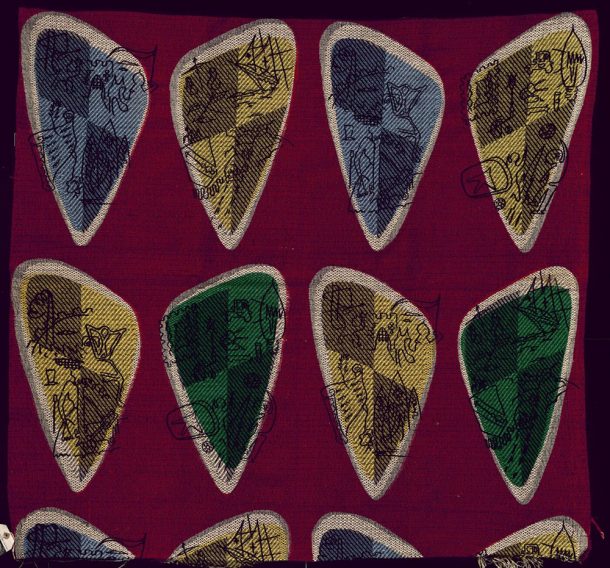

For the stand Tibor trialled a new technique; first weaving a textured base cloth, then screen printing corresponding motifs over the top. It depicted abstract emblems of the history of Britain and was titled ‘History of Shapes’. The design was made from a blend of Ardil and silk and used a metallic yarn. The V&A holds an original piece of ‘History of Shapes’ from the stand (T.65-2010). It was not, however, identified as being made from Ardil. Research undertaken as part of the Business of Fashion, Textiles and Technology project was able to link the object from the collection to the showcase – and therefore correctly identify it.

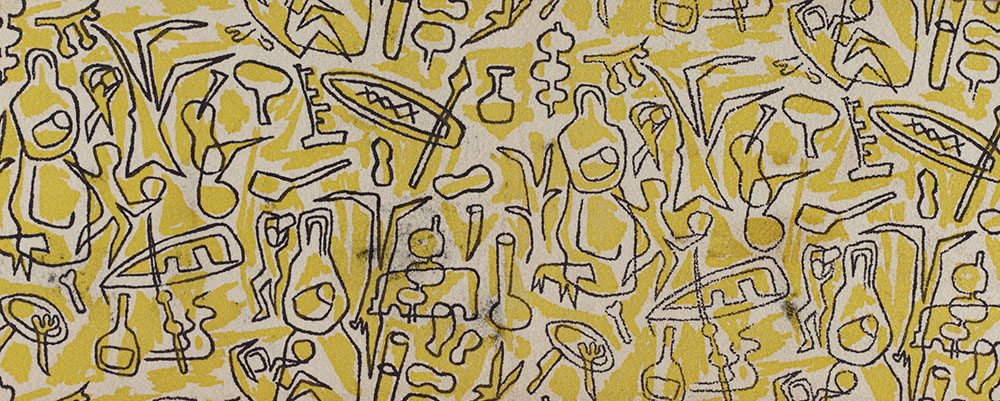

Tibor’s typical yarn palette would include wool yarns in different specifications, combined with viscose and Lurex wefts woven on a cotton warp. Ardil blended well with all these fibres and would have been complementary to his existing products. After the commissioned piece, Tibor continued to work with Ardil yarn, using it across his range of furnishing fabrics. Tibor was so taken with Ardil he created a distinctive design celebrating peanuts entitled ‘Harvest’. Using the unusual technique he had developed with ‘History of Shapes’, ‘Harvest’ has a woven Jacquard background, which was then screen printed. The motifs in the design are an abstract illustration of the process of harvesting peanuts.

Despite so much early promise, and a huge marketing effort on the part of ICI, the Ardil factory closed suddenly in 1957. Sales of Ardil were struggling, failing to improve year on year and the instability of the fibre proved too much of a gamble for many manufacturers. After an initial post-war spike, the price of wool began to drop, undermining Ardil’s market position. Sourcing the high yield of peanuts needed to manufacture Ardil in volume was also proving difficult as the supplies simply weren’t available. Finally, newly developed synthetic fibres such as ICI’s own Terylene were favourable with manufacturers and consumers alike than the less reliable protein fibres. Ultimately, Ardil was written off by ICI as a failed experiment.

In recent years we have begun to recognise the huge detriment synthetic textiles such as Terylene cause to our environment and additionally question our high levels of fashion consumption. In this context we are beginning to revaluate our materials and what properties we desire from them. Though previously dismissed in favour of petrochemicals, regenerated protein fibres could offer a much more sustainable solution for contemporary textiles; as they made from food waste, a good substitute for natural protein fibres such as wool and could in theory be composted at the end of their useful life. With advances in modern chemistry, we can also begin to address previous hindrances such as tensile strength and reduce the harmful chemicals used within the process of making. As this project demonstrates, archives are an invaluable resource for the development of future materials as we can learn from our past endeavours. See here for further reading on this research from the Business of Fashion, Textiles and Technology.

With thanks to Tibor Ltd.