It’s never too soon to become a design thinker. Children develop a rudimentary understanding of what things are made from at an incredibly young age. As soon as they can pick things up and put them in their mouths, they begin to recognise differences in texture, temperature, and taste.

As we grow, our understanding of these differences becomes more sophisticated. Variables such as weight and density, or strength and flexibility come in to play. Eventually children’s understanding of materials moves beyond simply understanding physical properties and encompasses how those properties can be applied. When is a bendy material more useful than something brittle? Or a soft one better than something hard? This is a key moment in our development of what could be called ‘design thinking’. Design itself is an applied discipline, and the ability to use different materials in a purposeful way demonstrates a real design approach.

But before we look at how Young V&A will engage children with different materials, it’s worth taking a step back – and thinking about why material choice is such an important part of designing.

As well as deciding what an object should look like and how it should work, designers must also resolve out how it will be made and what it will be made from. Simply put, will a material allow the object to be made and used in the way in which the designer envisages? In extreme cases designers will push the properties of materials to – or even beyond – their limits. Verner Panton, for example, had to wait years before plastic technology had progressed enough to make his cantilevered chair as he originally envisaged.

In his book The Design of Everyday Things, Don Norman discusses how certain materials can provide visual clues (affordances) that enable people to understand how to interact with them. For example, soft padding or rubberised grips often indicate parts of an object that are mean to be held.

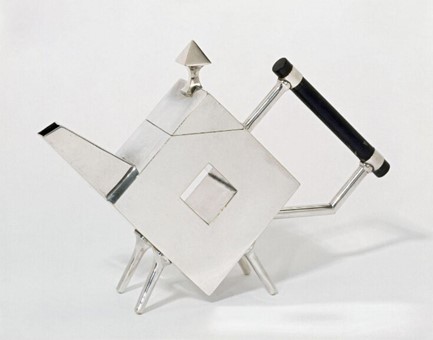

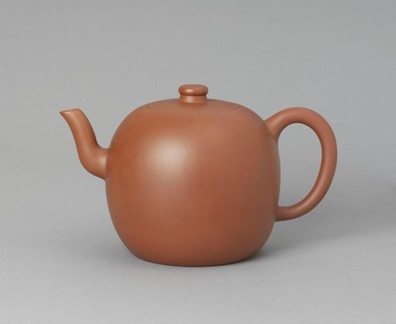

But materials also carry meanings that extend beyond the purely practical. Certain materials can signify luxury or status. Even an object as seemingly simple as a teapot can be transformed by a change in the material used to make it. This is evident from even the quickest glance at the V&A’s collection, where the relative opulence and luxury of a silver-plated teapot by Christopher Dresser can be contrasted with a comparative asceticism of a modest unglazed clay teapot (in this case a replica of one that once belong to a 17th- century Chinese monk). These materials choices are equally practical – both objects are perfectly adequate teapots – but they speak to the different needs and tastes of the respective users.

Unglazed brown stoneware

Tradition and convention also play a part in a designer’s choice. Certain products may be made from stone or metal because that’s how it has always been done and the people who buy those products feel safe and secure within those traditions. Children, however, are not yet conditioned by such conventions and are much more willing to be experimental in their choices.

There is also a more recent – and more urgent – factor that has come to dominate much of the public conversation around design and materials: sustainability. The designer and educator Victor Papanek (Design for the Real World, 1971) once wrote that ‘there are professions more dangerous than industrial design, but only a few of them’. Papanek was referring to the role that design has played in creating the consumer-focused society full of disposable products made from toxic materials that we now know to be so damaging to ourselves and the planet. However, a new generation of designers are using design to address the climate emergency, rather than contribute to it.

In 1992 Jane Atfield designed a chair constructed from a flat sheet of recycled plastic. There was nothing especially unusual about the chair’s design – it could have been made from any other sheet of flat material; plywood, MDF or even metal. The choice of recycled plastic, however, makes the chair significant. As one of the first products that celebrated its sustainable credentials so visually and confidently, it became emblematic of a new sustainable design movement.

Recycled high density polyethylene board

There are other ways a designer can incorporate sustainability into their work. If a product is made from a stronger material, it might not need as much packaging. Or perhaps by utilising a non-toxic dye from a factory that relies on renewable energy. Slowly, albeit too slowly, designers’ choices might mean that rather than us having to consciously choose a sustainable product, all products will have sustainability built into their design and manufacturing processes.

These examples only scratch the surface of how important material selection is to design, and how any museum with design collections must engage with these issues. Looking at the things around us, and questioning what they are made from, is as important for users and consumers of design as it is for the actual designers. And equally important – perhaps even more important – for children and young people. But how do we go about doing that in an engaging and appropriate way?

Our approach starts with our very youngest visitors. Babies and toddlers are obviously not making any applied material decisions yet, but they are already playing with materials and exploring the diversity of the material world. Displays in our Play Gallery will allow pre-walkers to explore different textures and materials in a playful way and at their own speed. Specially created displays will place objects within tactile and sensory environments that mimic textures of the objects. This will enable babies to make direct connections between the objects they are seeing and the textures they are experiencing.

At the other end of that scale are the 11 – 14 year olds who represent the upper range of our target audience. Our consultation and co-design sessions with young people highlighted how the climate emergency is one of their main interests and areas of concern. By looking at materials through the lens of climate change we can introduce material design in a way that is engaging, relevant and urgent.

Our galleries will showcase objects that exploit sustainable materials in different ways, such as the Belgian brand ecoBirdy – which turns broken toys into children’s furniture. This specific use of toys – as opposed to generic plastic – engages children with both the materiality of the product as well as the lifecycle of their toys.

We want to show striking objects that we can use to talk about materials. The Well Proven chair by Marjan van Aubel and James Shaw incorporates waste wood generated by the timber industry mixed with a non-toxic bio-resin. The resin acts as a form of glue, binding the woodchips together to create a porridge-like material that can then be moulded and left to harden. Importantly, the material choice is impossible to ignore. The chair begins a conversation.

American ash, wood chipping and bio resin

We will also show more unusual materials, like mycelium – a mushroom-like fungus that can be grown in a lab incredibly quickly using minimal energy. Mycelium+Timber is a project by Sebastian Cox and Ninela Ivanova who have designed and made a series of products that combine mycelium with waste wood. These objects challenge our preconceptions of what the objects in our homes can be made from and suggest a future in which things are grown rather than manufactured.

Image by Petr Krejci

Like Jane Atfield’s 30-year-old chair, these projects all share a very distinct, visual, and confident link to their materiality. What they are made from is obvious, and obviously different from the norm. This immediacy and instant appeal are an important part of our strategy to engage children and young people, and foster design thinking from the earliest age.