At times of great social upheaval, the arts help society understand events, deal with complex emotions and recover from collective trauma. As we enter the final year of commemorations marking 100 years since the end of the First World, the conflict continues to have a significant presence on the UK stage. Recent years have seen revivals of productions such as Birdsong and War Horse and new works including Balletboyz’s Young Men. Journey’s End is one of the most commonly revived plays of the First World War and will grace the silver screen in 2017.

Written by R C Sherriff in 1927, Journey’s End draws on the playwright’s experience of combat in the First World War. Set in an officers’ dugout over a period of four days in 1918, it is a story of comradeship, fear and heroism.

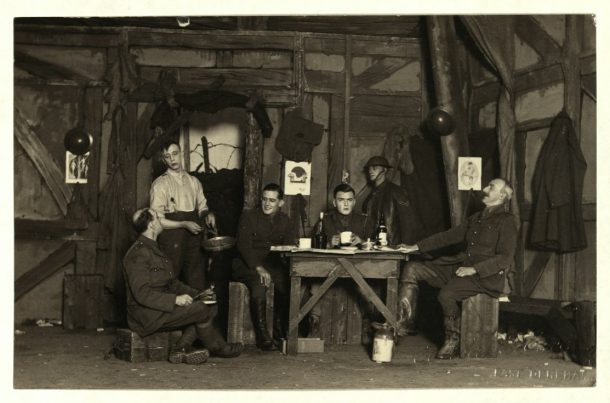

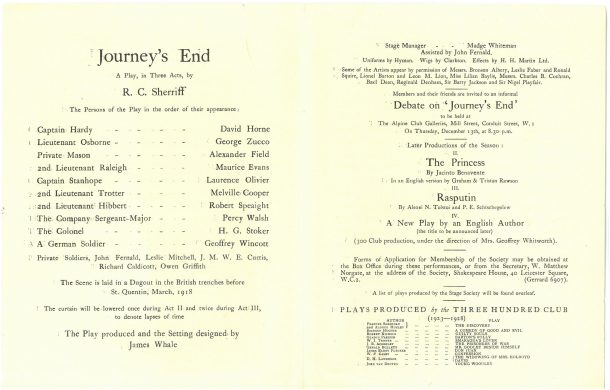

At first, Sherriff struggled to secure a West End performance of the play with many potential producers concerned that audiences would not want to watch a production about war, not least one without a leading lady or any female characters. After much consideration, The Incorporated Stage Society, a private members society that mounted performances of new and experimental work, agreed to include two semi-staged performances of the play in its Winter programme.

Opening at the Apollo Theatre on 9th December 1928 and starring a 21-year-old Laurence Olivier as Captain Stanhope, the play proved to be a critical success. Reviews commended Sherriff’s unromanticised portrayal of the realities of war and its emotional power noting that the play was worthy of a longer public run.

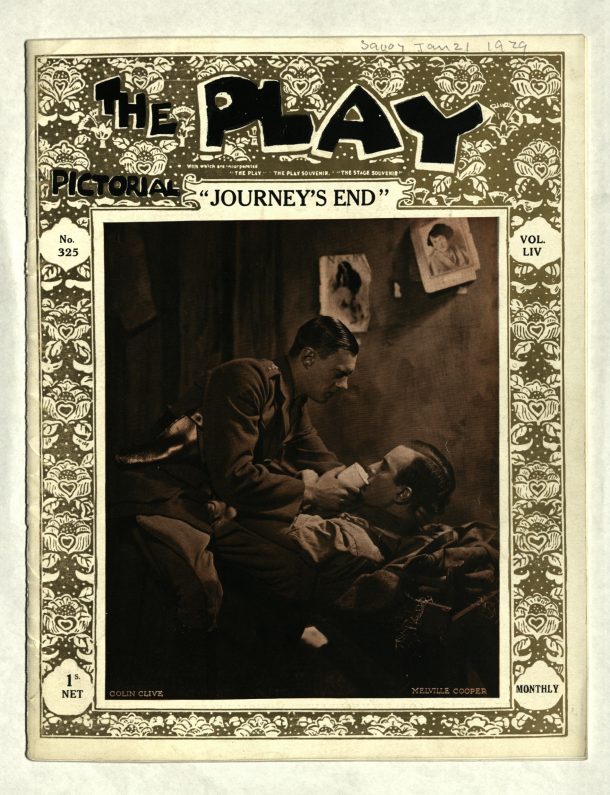

In January 1929 the play transferred to the Savoy Theatre under producer Maurice Browne. Sherriff was keen to use the original cast from the Stage Society performances but Olivier was already committed to star in a production of Beau Geste and so Colin Clive took over the role. The play was warmly received by audiences with Winston Churchill pronouncing it “brilliant”. Standing ovations met the cast on opening night and demand for tickets resulted in the addition of three matinee performances a week. The BBC broadcast a wireless version on Armistice night 1929 and at a special performance for 320 Victoria Cross holders, Sherriff was applauded for a number of minutes.

Journey’s End is without doubt one of the greatest plays exploring the First World War with a poignant anti-war message. However, its anti-war message is complex. Histories of the war written in the 1960s present the British commanders as foolish men, far from the front line who needlessly sacrificed the lives of brave men in military blunders, and this idea pervades in the anti-war sentiments presented in Theatre Workshop’s Oh! What a Lovely War! and television’s Blackadder Goes Forth. Ultimately, it was Sherriff’s intention to produce a play which paid tribute to his brothers-in-arms and the virtues of duty, perseverance and comradeship which he experienced on the Western Front.

Whilst the war in Journey’s End reveals the tragedy of conflict for both sides, the play’s narrative reminds audiences that the deaths were not without purpose. For audiences in 1929, the Great War was not only in living memory, but its legacy was still visible with many families mourning the loss of loved ones and dealing with both the mental and physical wounds of conflict. For inter-war audiences, Journey’s End offered an act of remembrance where those left behind could commemorate the sacrifice of husbands, fathers, sons and comrades and look forward to a future of peace. As the Manchester Guardian printed in its 1928 review “Journey’s End should become an official play of all the peace societies in England. It is worth many million pamphlets.”

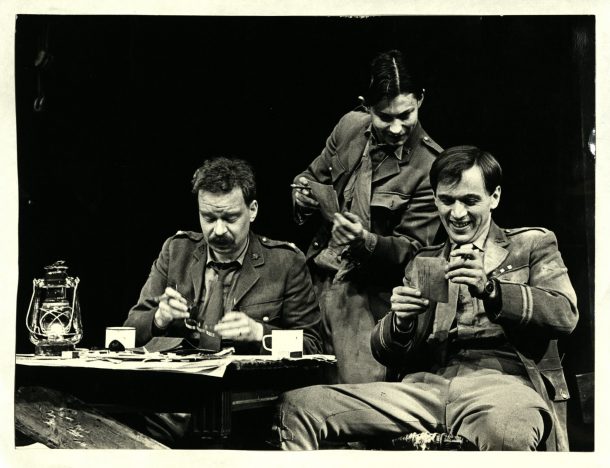

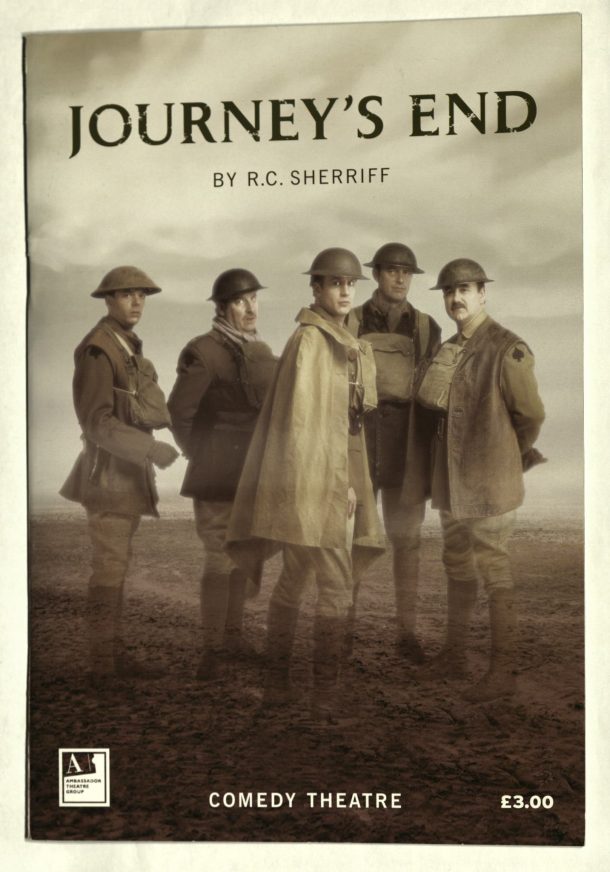

The powerful anti-war message of Journey’s End still resonates with modern audiences in a time when conflict shows no sign of abating. David Grindley’s 2004 production at the Comedy Theatre, London juxtaposed the play’s strain of dark humour with heart-breaking tragedy. 75 years after the play opened at the Savoy Theatre, reviews of Grindley’s production note the lasting power of the piece, the impact of the intimate setting and the crafting of complicated, recognisable characters. Rather than concluding with a traditional curtain call, the production ended with the cast standing silently before a memorial inscribed with the names of the fallen, encouraging the audience to not only congratulate the cast, but to remember the sacrifice of the brave, ordinary heroes of the First World War.

To explore the V&A Theatre and Performance Collections visit Search the Collections and Search the Archives.

Sherriff was applauded for a number of minutes

If you are thinking about the comparison of the previous and current version of it then first of all I would like to suggest now New version of the Microsoft is more compatible.

Strange places here.

I think it’s David Grindley not David Brindley