As part of my Master of Science degree in Conservation, I recently completed a placement with the V&A’s Conservation team, which unearthed new information on the origins of a mysterious stone sculpture believed to be from the Longmen Grottoes in China, one of the most famous ancient archaeological UNESCO sites in the world.

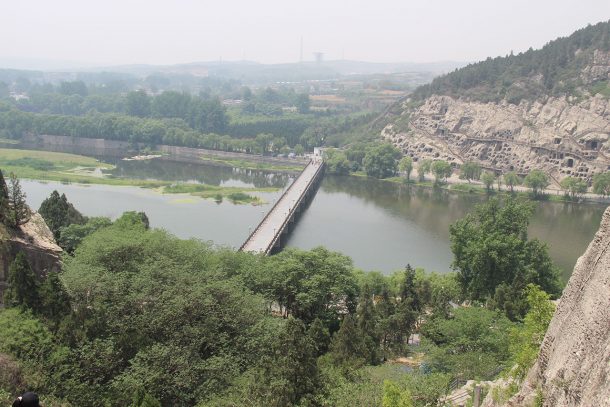

In 1920, the V&A acquired the stone head of a Buddhist figure, believed to be from the Longmen Grottoes in Henan, China (according to Longmen liusan diaoxiang ji, a compendium on sculptures from that area). The grottoes, comprising over 1,350 caves, were built from 386 – 1130 CE and contain some of the finest examples of stone sculpture in ancient Chinese art, including 100,000 Buddhist images. Grotto stone sculpture was an important type of art in ancient China, and the styles produced from this period greatly influenced Buddhist sculptural traditions in other Asian countries.

The V&A’s Sculpture Conservation team were due to carry out some small repairs to this Buddhist stone head as part of its long-term care. This created the perfect opportunity to gather more evidence about its uncertain provenance by examining possible associations with the Longmen Grottoes and using scientific analysis methods to uncover invisible yet key information about the object’s materiality.

The first grottoes in the Longmen complex were constructed in 386 CE under the orders of Emporer Xiaowen of the Northern Wei dynasty, to commemorate his momentous removal of the capital from Datong to Luoyang. Subsequent rulers continued to add to this important site until 1130 CE. Each expansion of the grottoes over the centuries left a historical trail of different sculptural styles that characterise each period of construction. The stylistic traits seen on the museum’s stone head – rectangular, full features and graceful curves – are characteristic of the Tang dynasty, which implies a dating of 618 to 907 CE.

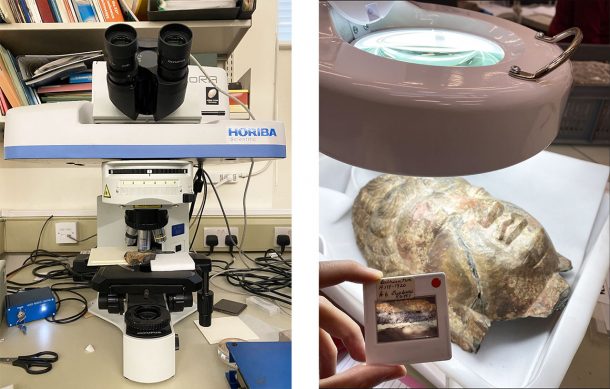

We used a scientific analysis method called Raman spectroscopy – a non-destructive analysis technique that can identify the distinct chemical compositions of stones. Like fingerprints, each stone sample has a unique chemical composition, and Raman analysis can distinguish between different subtypes of limestone. The original limestone quarry used for the earliest Longmen caves was made of dolomitic limestone, but this was depleted around 535 CE, and sculptors began to use a neighbouring quarry instead, made of calcitic limestone. Chinese sculptors favoured dolomitic limestone because of its hardness and durability – optimal qualities for sculpting – compared to the more fragile calcitic limestone. So identifying the sculpture’s limestone subtype could point to whether it was made before or after the approximate year 535 CE.

Archaeological scientists Jian Zhu and Changsui Wang from the Chinese Academy of Science in Beijing organised a timeline of the Grottoes by limestone subtype in their 2012 study on Longmen limestone. The general direction of transition from dolomitic to calcitic limestone went from north to south, earliest to latest cave sites.

Another study by Jinglong Liu also found that calcitic limestone sculptures belonged to the grottoes’ middle and southern areas on both the Western and Eastern Hills. This common composition is because the two sides were once part of the same mountain range before the fault (which is now the Yi River) divided it, creating the valley that is now the Longmen complex. Visible differences in the cave sites and the evolution of sculptural styles also follow this general pattern: the northern zone is densely populated with sculptures and contains few rock fractures and thick rock layers, whereas many caves in the southern zone are empty due to the poorer quality of the limestone and thinner rock layers.

Using Raman analysis on our sculpture revealed highly detailed information on the stone’s chemical composition and crystalline structure. The results revealed the presence of calcite, the main component of calcitic limestone, and there was no dolomite, the presence of which would have suggested dolomitic limestone. We also inspected the sculpture under UV light, revealing an old break that had once been treated with an adhesive.

According to Pinyan Zhu and Amy McNair from the University of Kansas, both art historians and experts on grotto art from Longmen, the stylistic features of the stone head resemble those found in the Eastern Hills. Such figures date to the late 7th to early 8th centuries and suggest that the V&A’s head may have originated there. Of all the comparable examples found in other museums, it most closely resembles another stone head from Longmen found in the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, which is identified as from Leigutai Central Grotto, one of the larger caves in the Eastern Hills, as well as a stone head in Princeton University Art Museum. All three heads display the plumper features that are characteristic of styles produced after 730 CE, when sculpting activity became concentrated in the Eastern Hills and southern end of the Western Hills, around the Jinandong area.

Judging from the head’s small height of 31.8 cm, the cave from which it came was probably also modest in size. In general, sculpture sizes corresponded to the caves that housed them. By comparison, the large Buddha head of Leigutai Central Grotto measures 66 cm high and matches its cave’s grand scale. The V&A’s scientific results therefore suggest a more precise location, housing context, and dating than those found in our records before.

Much of the cave shrines in Longmen were pillaged during the 1920s and 30s, and many of the remaining sculptures have missing heads or faces. The V&A’s stone head may well have once been among them. Museum records show that the head was purchased in 1920 from S.M. Franck & Co. Ltd., an importer of ‘Near and Far Eastern’ works of art. During this time, China experienced a period of strong foreign control over its trade, and many sculptures were removed from the Longmen Grottoes for export to Western collections, such as the National Museum of Asian Art in Washington DC and Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. This export history is consistent with the acquisition date of the V&A’s head. Our investigation has not only improved the accuracy of museum records about the sculpture’s provenance, we also hope it will help other researchers and institutions interested in Chinese art to demystify the fascinating history of the Longmen Caves.

Hi!Thank you for your article. Has this Buddha head been on display in recent years?How could I acquire the information?