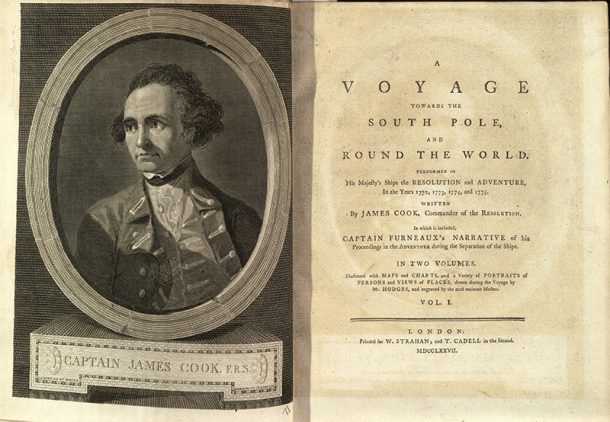

240 years ago, on the 30th July 1775, a remarkable voyage came to an end at Portsmouth. Having set sail in 1772 the “Resolution” and its sister ship “Adventure”, led by Captain James Cook, had spent three years traversing the Southern Hemisphere, recording previously un-charted waters and islands and making contact with their inhabitants. On board the “Resolution” was a young painter whose thirst for adventure took him closer to the South Pole than any artist before him.

To active Hodges, who with zeal sublime,

Pursued the art, he lov’d in every clime;

Who early traversing the globe with Cook,

Painted new life from Nature’s book

(Hayley, 1809, p. 260)

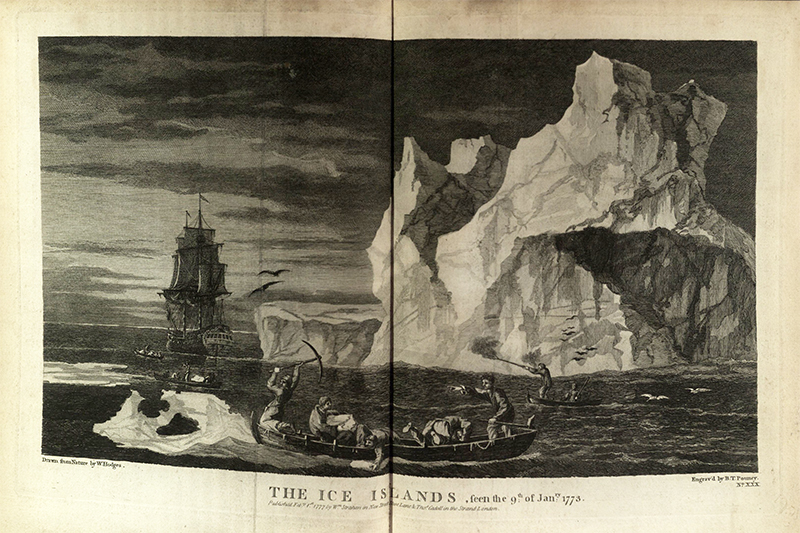

So reads William Hayley’s tribute to his friend the landscape artist William Hodges (1744-1797). Hodges sailed the South Pacific Ocean with Captain Cook, recording the sights and encounters of the voyage. The 35 etchings produced from his work after the expedition’s return to England in July 1775 can be seen in the National Art Library’s copy of Cook’s “A voyage towards the South Pole and round the world”

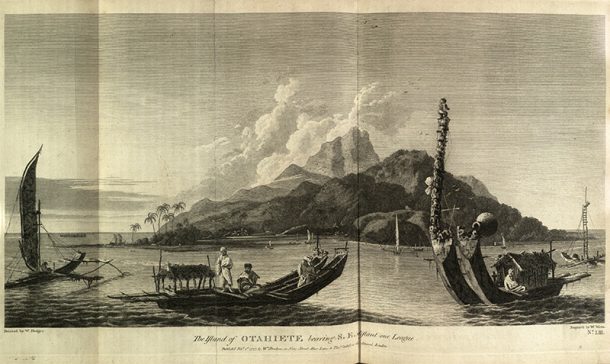

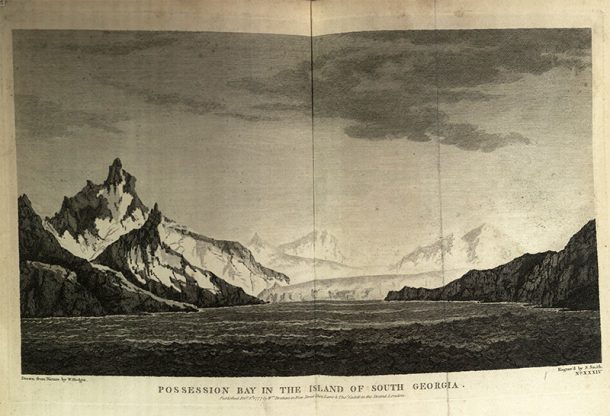

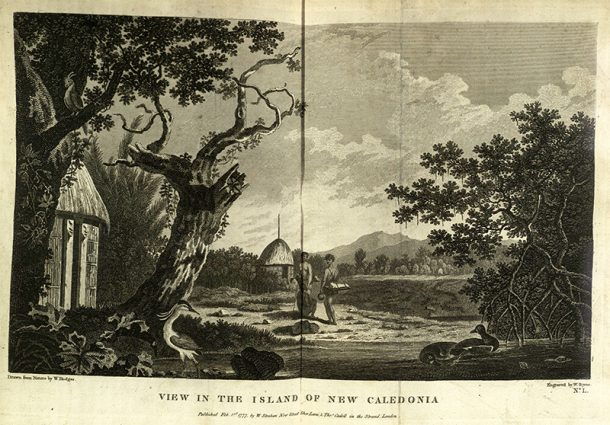

In the closing years of the 18th century European mercantile ambition united with Enlightenment theories and scientific fervour to promote maritime exploration on an unprecedented scale. Perhaps the most famous of these ‘voyages of discovery’ are James Cook’s three voyages around the globe between 1768 and 1780. These voyages intended to, on the one hand, identify unvisited lands and shipping routes useful to Britain’s growing demands for trade, and on the other to elicit scientific discoveries. In an age long before photography, artistic representation of newly encountered lands and the people, plants and animals that inhabited them, was crucial to transmitting new scientific knowledge. Also of vital importance during this period of fiercely contested trading and European war was the depiction of coastal sites with images of harbours and coves providing details of interest to mariners. In fact interest was sufficiently strong that as well as Hodges’ “elaborate off shore views”, three seamen aboard the Resolution included coastal profiles and harbour views in their logs (Smith, 1960, p. 50).

The importance of art was such that The Royal Society and the Admiralty engaged artists to travel on expedition ships, and it was under this aegis that Hodges joined Cook’s crew. Deference to art had its limits though and was no match for the Admiralty’s (and Cook’s) duty to the safe execution of the voyage. From 1768-1771 Joseph Banks had served under Cook to record his first voyage. However, by the time the second voyage was due to set sail in 1772 Banks had decided his retinue, including the artist Johann Zoffany, required a specialised space aboard ship. When his demands for an extra deck on the Resolution rendered the vessel unseaworthy, and were thus refused, Banks withdrew himself and his artists from the expedition. By this happenstance, William Hodges found himself ship’s artist and heading toward the South Pole.

Aged 28 and already a seasoned landscape painter, having attended William Shipley’s drawing school and then apprenticed to the foremost landscape artist of the day, Richard Wilson, Hodges embarked on his adventure tasked with making “drawings and paintings of such places in the countries we touch at, as might be proper to give a more perfect idea thereof” (Cook, 1777, p. xxxiv)

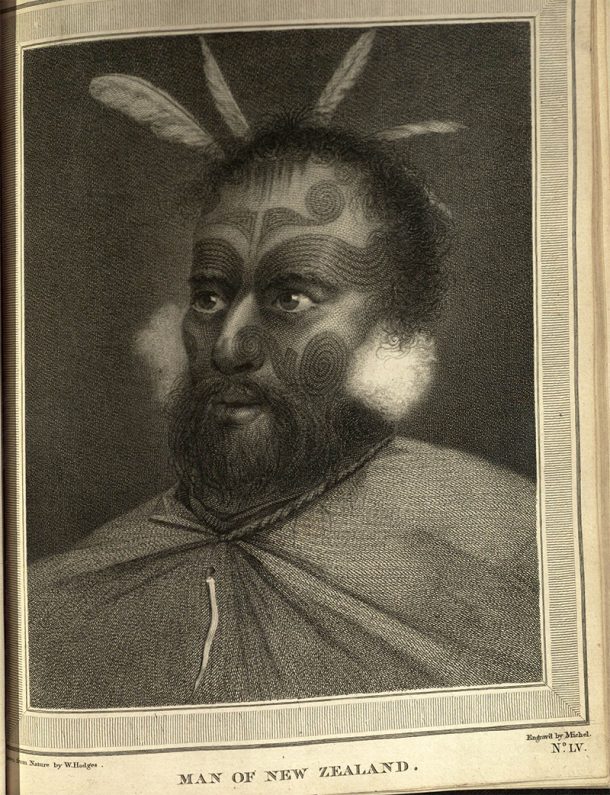

Although not known as a marine painter (Archibald, 2000) he had exhibited “A view of London Bridge from Botolph wharf” at the Society of Artists in 1766 (Society of Artists of Great Britain, 1766) and won awards at the Royal Society of Arts in 1762, 1763 and 1764 for “River Views” (Wood, 1913, p. 183) which implies he was no stranger to depicting marine vessels & waterscapes. Now he was engaged to provide “snapshot” images giving a sense of the action, atmosphere (both literal and emotional) and progress of the voyage, a task for which his landscape training stood him in good stead. Not to underestimate his skill at capturing detail, the clothing and localised body adornments of the islanders is also meticulously recorded in his landscapes.

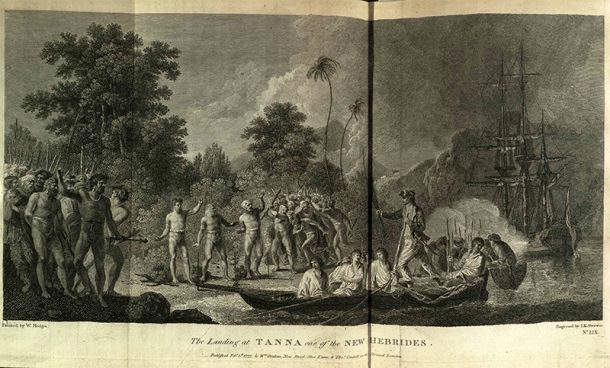

During the voyage the ship’s naturalists, John and George Forster, and its astronomer and meteorologist, William Wales, all took particular interest in the atmospheric, meteorological, and visual phenomena visible in the Southern Hemisphere so it is no surprise to see such effects given special attention in the illustrations (Smith, 1960, p. 38). “The landing at Tanna” is an especially good example of meteorological effects used for dramatic emphasis as the brooding clouds over the sea break to let the sun illuminate the islanders on the beach.

Not to be overlooked, the local fauna also make an appearance in several of Hodges’ works and in the associated etchings. For naturalists not lucky enough to have travelled with the expedition these images provided the first view of newly recorded species in their natural environment.

The etchings in “Voyages” are derived from Hodges’ drawings and sketch paintings; when the voyage made landfall at Portsmouth in July 1775 he was retained by the Admiralty at the sum of £250 per annum to develop his on-board works. As well as producing five large scale paintings to be kept in the Admiralty collection Hodges was charged with overseeing a group of etchers, many of whom were celebrated in their own right, to provide illustrations to Cook’s soon to be published account. Bartolozzi, Basire, Byrne, Caldwall, Hall, Lerperniere, Pouncy, Sherwin, Smith, Watts and Woolett were all involved in representing the newly encountered lands of the South Pacific to an eager European audience.

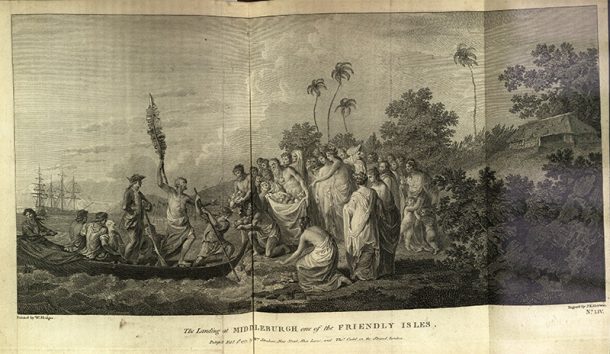

At this point it is important to note some contention over the accuracy of the etchings. At the time of the second voyage Neoclassicism still held significant sway over artistic theory and encouraged the classic idealism which is obvious in many of the plates. The placing of the figures, their poses and the use of drapery is intended to show nature “in her perfect form” and “what those perfect forms were the artist could only learn by a close study of the ancients and their Renaissance disciples” (Smith, 1960, p. 1). Thus in terms of both composition and portraiture a Classical Greek or Roman ideal was aspired to. Grecian drapery and statuesque postures are certainly apparent in Hodges’ sketches but these were taken to an extreme in many of the etchings. The “Landing at Middlebrough” etched by J.K. Sherwin was condemned by one of the ship’s scientists, George Forster, for its “Greek contours and features” which he considered an unfaithful artistic licence (Quilley & Bonehill, 2004, p. 136)

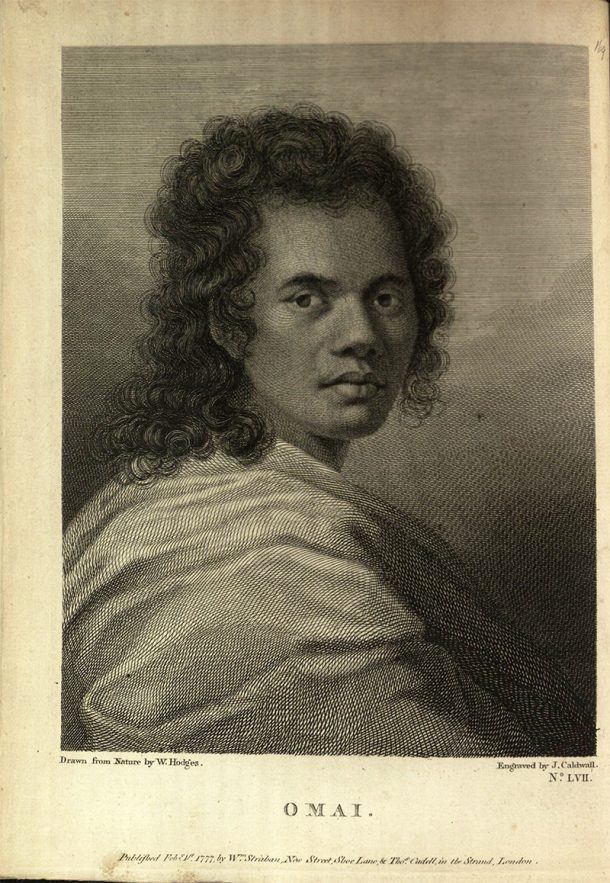

It can be argued that the “Portrait of Omai” highlights the classicizing zeal of the European artist even more clearly when compared with Hodges’ oil portrait of the same subject (held in the Royal College of Surgeons Hunterian Art collection). Although some insist that the discrepancy is the result of the limit of the engraver’s skill and not born of a desire to mislead (Joppien & Smith, 1985, p. 107) there can be no doubt that Hodges’ Omai, albeit with somewhat classic drapery, is a very different man to that of the etching that appears in “Voyages”.

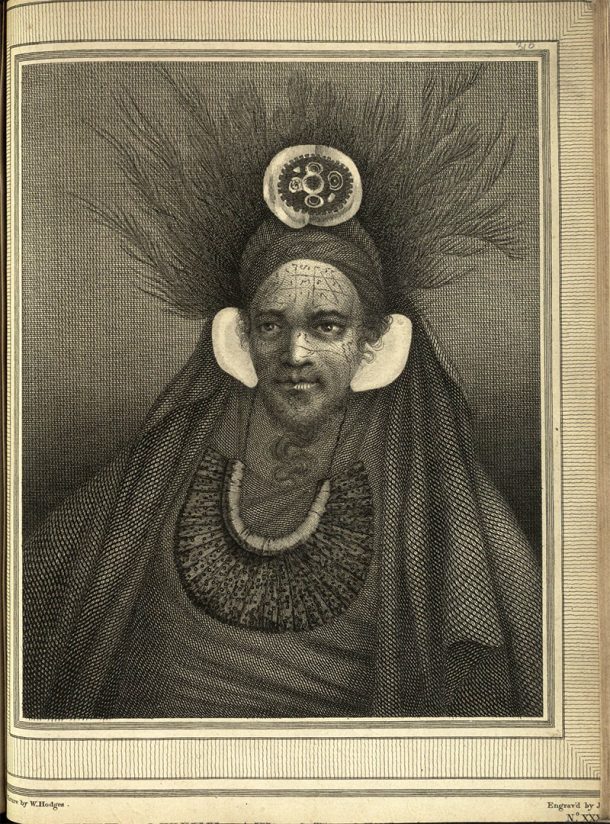

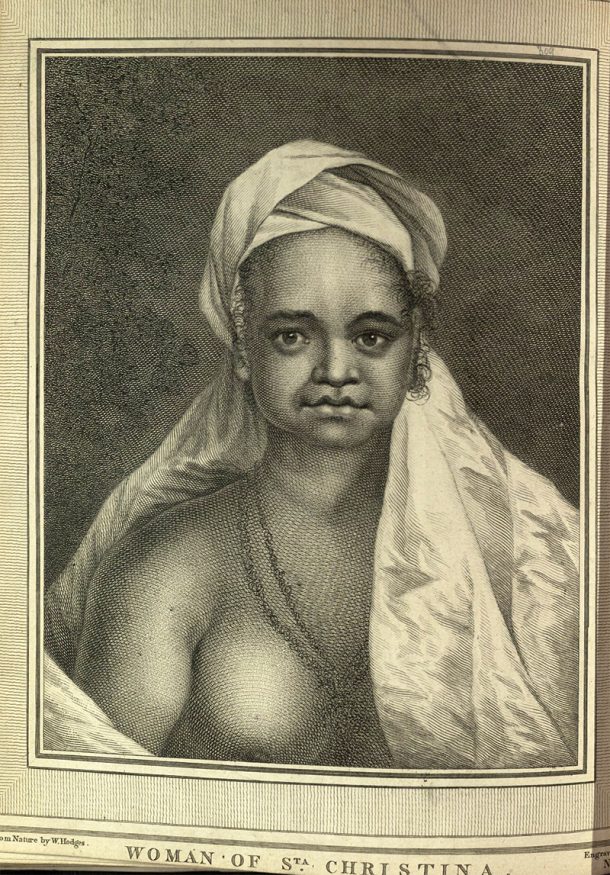

Whether such discrepancies were the result of limited skill, a desire to conform to popular artistic theories of representation, or even to make the images more saleable to a European audience remains a contentious issue. There are however several portraits in “Voyages” which appear to stay truer to Hodges’ original sketches, depicting localised body adornments and ritual ornaments:

The works produced by Hodges in the field and the etchings that were derived from them provided their 18th century audience with an awe inspiring visual account of these newly encountered lands. 240 years later, Cook’s “Voyages” provides us with an insight to 18th century notions of identity, art, and society, as well as the skill of the artists employed to record them.

Further reading

Archibald, E. (2000). The Dictionary of sea painters of Europe and America. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club.

Cook, J. (1777). A Voyage towards the South Pole and round the world : performed in His Majesty’s ships the Resolution and Adventure, in the years 1772, 1773, 1774 and 1775 (Vol. 1). London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell.

Hayley, W. (1809). The Life of George Romney. London: T. Payne.

Joppien, R., & Smith, B. (1985). The art of Captain Cook’s voyages : volume two : the voyage of the Resolution and Adventure 1772 – 1775. New Haven: Published for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art by Yale University Press.

Quilley, G., & Bonehill, J. (2004). William Hodges 1744-1797: the art of exploration. London: Yale University Press for The National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

Smith, B. (1960). European vision in the South Pacific, 1768-1850. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Society of Artists of Great Britain. (1766). A catalogue of the pictures, sculptures, designs in architecture, models, drawings, prints, &c. : Exhibited by the Society of Artists of Great-Britain, at the Great Room in Spring-Garden, Charing-Cross, April the twenty-first, 1766. Being the seventh y. [London]: Printed for the Society, by William Bunce, Russel-Street, Covent-Garden.

Wood, H. T. (1913). A history of the Royal Society of Arts. London: J.Murray.