The answer to that question depends on where and when you come from. As an apprentice working in the National Art Library I handle many books every day and I am always amazed at the variety of styles I come across. Every time I encounter a poor thing which is damaged I find myself suppressing my bibliomaniac horror and examining its secrets. Of course, there are hundreds of ways to make a book, but in this post I will briefly examine three books in the NAL from different eras and attempt to reveal their inner workings!

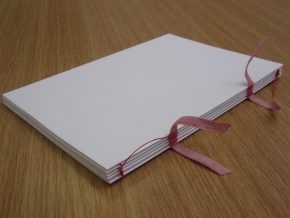

The earliest texts bound into a form we would recognise as a book were created by early Christian communities in Egypt. Few of these Coptic bindings survive, and they are mostly in fragments – but you can still tell a lot about how they were made from these pieces. Some fragments have survived from as long ago as the second century AD.

The text was written by hand on sheets of papyrus or parchment which were folded and arranged in sections. A section is a number of sheets folded and nested inside one another. The book was constructed from multiple sections, and this basic arrangement remains unchanged through the history of Western bookbinding to the present, except in cheaper modern paperbacks. The covers of the earliest Coptic books were made of sheets of papyrus pasted together to create a sturdy cover, but later wooden covers became more common.

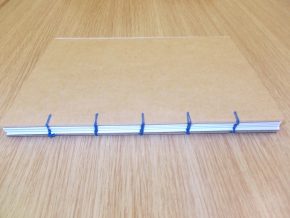

The Coptic book was bound by sewing in and out of the sections. The cover was attached to the first section with loops of thread and the rest of the sections would have been added by sewing through the folds, making chain stitches down the spine to secure them together. The binding was completed by attaching the other cover in the same way as the first. There were many variations but this basic method remained the same.

This model demonstrates what a Coptic book would have looked like:

As early as the fourth century AD Coptic books were being covered with decorated leather. The technique remained in use for almost a thousand years but in Europe new methods developed during the Middle Ages.

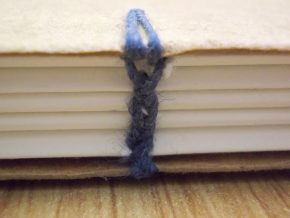

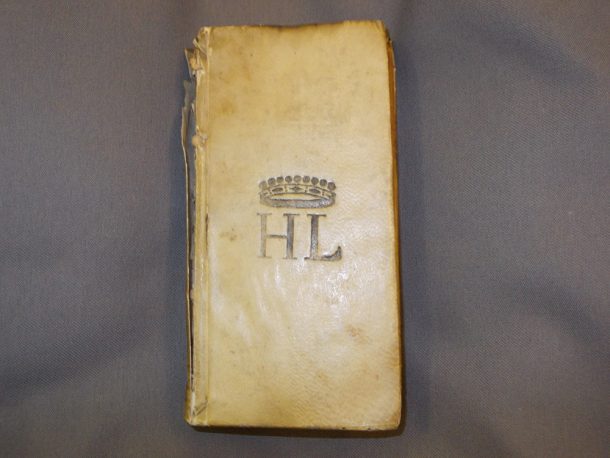

From this period most books were sewn with added ‘supports’. There were many types including cords, leather thongs and strips of vellum (the thinned skin of a calf). It is these supports that create the distinctive ridges on the spines of old books. Below is an example of a lovely little book covered in vellum and sewn on cords.

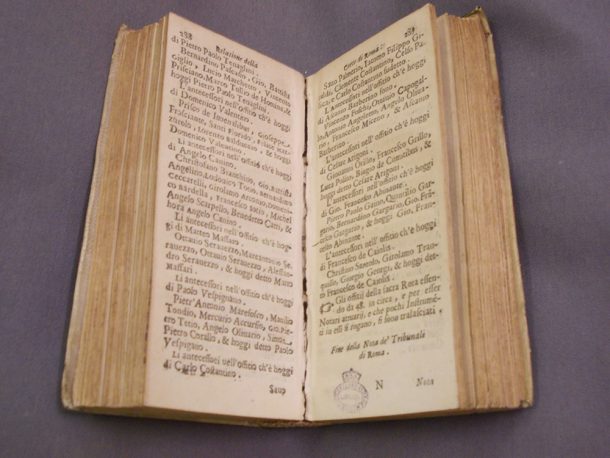

By the time the printing press entered popular use books were almost exclusively being made of paper rather than papyrus or parchment, but the pages were still arranged in sections like the Coptic bindings. The covers were mostly wooden until the end of the fifteenth century when they began to be superseded by boards made by pasting together many sheets of paper.

This type of book was bound by sewing through the folds of the sections and around the supports. The spine was glued and covered in waste paper once it had been hammered into a rounded shape.These developments allowed larger amounts of text to be bound together more securely. The problem with the Coptic technique is that the only thing holding the book together is thread – if that fails the whole book falls apart. With the use of supports and glue the structure has a much greater chance of staying intact.

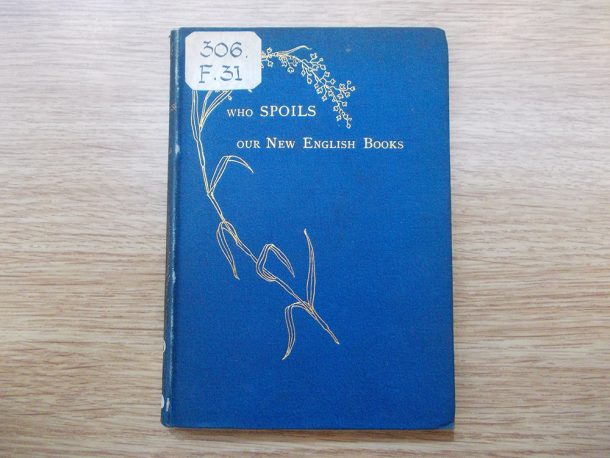

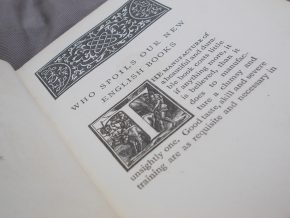

Now we pass to the nineteenth century, an era of increasingly cheaper production which brought books within the reach of the masses. Machines for sewing the book, tightly woven book cloth for covering rather than leather, and many other innovations reduced costs.

The cloth bound nineteenth book was constructed by sewing around supports as before. The supports used in this kind of book – a case binding – were usually linen tapes. The thread went along the fold of the section and came out to pass over the tapes, and at each end were chain stitches.

The spine was glued and covered in paper and loosely woven cloth which extended over its sides. This overhang of cloth was glued to the blank or coloured outermost pages (the endpapers) along with the tapes. If you look closely inside the covers of books in this style you can see the outlines of the tapes making just a slight bulge under the paper.

The ‘case’ of a case binding is the cover boards (now boards were being made from pulped rags and rope) and a piece of card or paper the length of the spine with book cloth glued on to cover them. In this style the sewing supports do not lace into the covers like they do on older bindings, instead the case is simply glued onto the endpapers and the book is complete.

As is this very brief survey of bookbinding techniques throughout the centuries. Of course, nowadays they usually just pile the pages up and glue them together!

Interested in bookbinding? We have plenty of books on the subject at the National Art Library as well as an incredible collection of examples of the art. Search for bookbinding under ‘subject browse (NAL subjects)’ on our catalogue here: catalogue.nal.vam.ac.uk.

How to work in such places?

Hi Lynn,

Interested in bookbinding? We have plenty of books on the subject at the National Art Library as well as an incredible collection of examples of the art. Search for bookbinding under ‘subject browse (NAL subjects)’ on our catalogue here: catalogue.nal.vam.ac.uk.

All the best,

Samuel Revell